Being among the earliest readers and admirers of Brown Pundits, it was an honor when Omar Sahib invited me to write here few months ago. Since I blog about diverse topics (like most of you), I hesitated that something might come across as irrelevant. I’ll keep sharing my thoughts on various topics from time to time. Just starting with a piece on Ibn Tufayl’s Hayy Ibn Yaqzan.

It is hard to imagine a young kid finishing high school without ever coming across The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe? Written in 1719 by Daniel Dafoe, it is among the claimants of the auspicious stature of first English novel, and widely believed as a true travelogue upon its inception. However, there is seldom a casual reader who can trace the legend back to the 17th century roots of literary tradition with an autodidact character at its center; and few are aware about the Arab-Spanish mentor of this optimism in human reason and contemplation, Ibn Tufayl (d. 1185).

It is hard to imagine a young kid finishing high school without ever coming across The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe? Written in 1719 by Daniel Dafoe, it is among the claimants of the auspicious stature of first English novel, and widely believed as a true travelogue upon its inception. However, there is seldom a casual reader who can trace the legend back to the 17th century roots of literary tradition with an autodidact character at its center; and few are aware about the Arab-Spanish mentor of this optimism in human reason and contemplation, Ibn Tufayl (d. 1185).

Almost six hundred years between Dafoe and him, we know very little about the life of Ibn Tufayl, except that he was a polymath, serving as a physician and adviser of Sultan Abu Yaqub Yusuf (d. 1184) of the Almohad dynasty ruling Morocco and Spain. It is unfortunate that his complete interdisciplinary work is lost, except his philosophical experiment involving an isolated autodidact, named Hayy Ibn Yaqzan; literally translated as Alive, Son of the Awake.

It is the story of a boy, the nature of whose existence is shadowy to an extent that there are two completely rivaling accounts of  his origins. One account ascribes his origin to spontaneous generation from matter; the other is necessarily a legendary human drama in which a royal infant somehow grows up away from society and culture. Being isolated from all intelligent life, he gradually becomes conscious, thereby discovering shame, jealousy, aspiration, desire, eagerness to possess and practical reasoning. He experiences love through affection of his foster doe, and death, as it ultimately departs.

his origins. One account ascribes his origin to spontaneous generation from matter; the other is necessarily a legendary human drama in which a royal infant somehow grows up away from society and culture. Being isolated from all intelligent life, he gradually becomes conscious, thereby discovering shame, jealousy, aspiration, desire, eagerness to possess and practical reasoning. He experiences love through affection of his foster doe, and death, as it ultimately departs.

To know is necessarily an obligation for Hayy Ibn Yaqzan. Desperately seeking meaning, his search guides him to explore various disciplines such as anatomy, physiology, metaphysics and spirituality. He deduces the presence of God through contemplating the unity of cosmos and its boundedness; and in his ascetic code of conduct, he seeks satisfaction and salvation.

After thirty-five years of isolation, he finally meets Absal, a hermit refugee from a land of conventional religious believers. In Absal, Ibn Tufayl modeled a religious divine who has learnt many languages to gain mastery of scriptural exegesis. Absal’s first reaction is a deep sense of fear for his faith as he encounters an exotic being. As they interact well, Absal endeavors to teach Hayy to speak and communicate, in order to make him aware of knowledge and religion.

However Absal soon discovers that Hayy is already aware of the truth, to envision which, Absal’s own intellect bears nothing except revealed symbols.

Judging Absal’s good intentions and the veracity of his message, Hayy proselytize to this religion and Absal introduces Hayy to his people. As Hayy gets familiarized with civilization, two basic questions continue to puzzle him in great deal. First, why people must need symbols to assimilate and express the knowledge of the ultimate truth; and why can’t they just experience the reality more intimately? Second, being completely oblivious to practical religion, he continued to wonder why there is an obligation to indulge oneself in rituals of prayer and purity.

He keeps on wondering why these people consume more than their body needs, possess and nurture property diligently, neglect truth by purposefully indulging in pass-times and fall an easy prey to their desires. He finally decides to accompany Absal to his land, thinking that it might be through him that people encompass the true vision and experience truth rather than believing it with their seemingly narrow vision.

What follows is a tale of a neophyte philosopher teaching ordinary people to rise above their literalism and open another eye towards reality. His interlocutors on the other hand, recoil in their apprehensions and being intellectual slaves to their prejudices, close their ears. He consequently realizes that these people are unable to go beyond their usual appetites. He also grasps that masses of the world are only capable to receive through symbols and regulatory laws rather than being receptive to unstained and plain truth. Both men eventually return back to their isolated world but this time Hayy as the teacher and Absal as his disciple. They continue searching their ecstasies until they met their ends.

Ibn Tufayl’s singularly survived legacy extends in diverse dimensions and its canvas is vast. Its theological and philosophical themes were employed and transformed throughout the various phases of European enlightenment.

It isn’t just one curious aspect that many centuries later, the metaphysically preoccupied Hayy Ibn Yaqzan is transformed into a shipwrecked sailor, predominantly occupying himself with inventions and utilitarian exploration of nature. As Malik Bennabi – an acute observer of modern condition – observes, the genius of both the narratives lies in characterizing the solitude of their respective protagonists. In this respect, time for Robinson Crusoe is essentially a concrete cyclic happening of acts, such as work, food, sleep and work again.

Nov. 4. This morning I began to order my times of work, of going out with my gun, time of diversion, viz., every morning I walked out with my gun for two or three hours, if it did not rain; then employed myself to work till about eleven o’clock; then eat what I had to live on; and from twelve to two I lay down to sleep, the weather being excessive hot; and then in the evening to work again. The working parts of this day and of the next were wholly employed in making my table; for I was yet but a complete natural mechanic soon after, as I believe it would do anyone else.[1]

This is pretty much the condition of a modern individual where the void of solitude is filled with work, each of us occupied  mechanically with the object at the centre of our world of ideas, diligently busy in constructing our own proverbial tables.

mechanically with the object at the centre of our world of ideas, diligently busy in constructing our own proverbial tables.

On the other hand, what fills Hayy’s solitude is an overwhelming amazement, the adventure starting by experiencing wonder in the ultimate nature of life and death of his beloved foster-mother, the gazelle.

When she (the gazelle) grew old and feeble, he used to lead her where there was the best pasture, and pluck the sweetest fruits for her, and give her them to eat. Notwithstanding this, she grew lean and continued a while in a languishing condition, till at last she died, and then all her motions and actions ceased. When the boy perceived her in this condition, he was ready to die for grief He called her with the same voice, which she used to answer to, and made what noise he could, but there was no motion, no alteration. Then he began to peep into her ears and eyes, but could perceive no visible defect in either; in like manner he examined all the parts of her body, and found nothing amiss, but everything as it should be. He had a vehement desire to find that part where the defect was, that he may remove it, and she return to her former state. But he was altogether at a loss how to compass his design, nor could he possibly bring it about.[2]

Thus, it is ultimately in the nature of failure to identify this defective part where Ibn Tufayl tries to locate an ineffable reality beyond the material.

Ibn Tufayl’s philosophical romance has been regarded as one of the pioneer autodidactic works surviving from medieval scholastic tradition [3]. But besides being an influential narrative — with rich literary possibilities and themes such as those transformed by a modernist like Dafoe — it was a precursor to important medieval interactions between the schools of Thomas Aquinas and Averroists, and invited modern appraisals from mathematician rationalists like Gottfried Leibniz [4].

Voltaire and Quakers admired it for its appeal to reason, and Bacon, Newton and Locke were possibly influenced by it to various degrees too. Traces of Ibn Tufayl’s original literary pointers are also found in Rousseau’s Emile, Kant’s Ground of Proof for a Demonstration of God’s Existence, Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels and Darwin’s Origin of Species among others.

Especially in the context of Muslim tradition, its contemporary value lies in rich possibilities to bridge gaps between reason and revelation. It lays down a perpetually self evolving construct where reason and reflection are the essential keys to the doors of timeless revelation. Ibn Tufayl’s voice still echoes loud, struggling to tell us that rejecting either would imply rejecting a part of truth.

_________________________________________

- Daniel Dafoe, Robinson Crusoe, Penguin Classics 2003

- Lenn Evan Goodman, Ibn Tufayl’s Hayy ibn Yaqzan: a philosophical tale, 1972.

- There have been attributions to an earlier work involving similar but limited themes to Avicenna.

- Samar Attar, The Vital Roots of European Enlightenment: Ibn Tufayl’s Influence on Modern Western Thought, 2010

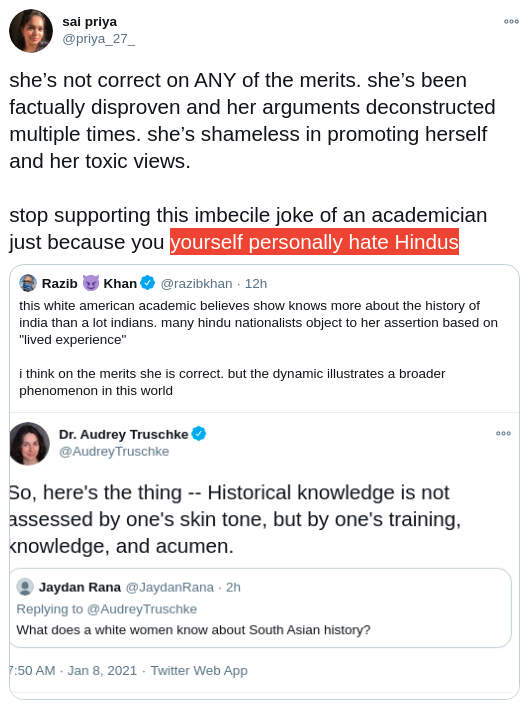

The identitarianism is straightforward. Despite the fact that I’m an atheist they regularly accuse me of being a Muslim. In some cases, this is an honest false positive. Look at my name! In other cases, they assume since I’m making fun of them, I must be a secret sulla with Muhammad or whoever. I’m against them, so I’m for their enemies, or with their enemies. Sometimes they revert to forms of racism (e.g., they are upper-caste Punjabis, so genetically superior, despite being J1 Dasyus!). The ultimate takeaway is the fixation on the group and historical identity, rather than updating to individual identity.

The identitarianism is straightforward. Despite the fact that I’m an atheist they regularly accuse me of being a Muslim. In some cases, this is an honest false positive. Look at my name! In other cases, they assume since I’m making fun of them, I must be a secret sulla with Muhammad or whoever. I’m against them, so I’m for their enemies, or with their enemies. Sometimes they revert to forms of racism (e.g., they are upper-caste Punjabis, so genetically superior, despite being J1 Dasyus!). The ultimate takeaway is the fixation on the group and historical identity, rather than updating to individual identity.