The reaction to my piece on caste by the Indian and Indian American Left has been interesting, and fraught with confusion.

First, the reaction by this Indian (now in America) Leftist is to accuse me of being an upper-caste Muslim. This is not that far from how Hindu nationalists react to me, which illustrates that certain mentalities are general, and the specific instantiations simply flavors on top of the common base. Most Indians are “identitarian” in such a deep way, whatever their ideology, that Americans would have to be impressed (if they are cultural liberals and racialists). If you scratch an Indian Leftist they aren’t that different from a Indian Hindu nationalist in their cultural presuppositions.

I am not an upper-caste Muslim in a literal sense, because a quick scan of my genome will show I’m a generic eastern Bengali, and more concretely caste is not a thing in Bangladesh anymore. I do have ancestors who are Hindu, as all people of subcontinental Muslim background do, and all I know is that most were Kayastha (on my mom’s side) and my paternal grandmother’s father was from a lineal Bengal Brahmin family (her father was very young when his father converted the family from what I recall, so he did not remember being a Hindu, though he did pass on some Hindu customs to my grandmother like the utilization of separate dishes). My paternal lineage, from where I get “Khan,” were landholders in their region of Bengal for a long time, and traditionally provided the ulema for the villages in the locality. We also funded the construction of many of the oldest extant masjids in the area.

It’s hard to deny that I have class privilege, given that my family was present in the professions or owned land for centuries. This, despite the fact that partible inheritance means that my “ancestral desh” (which I have never physically been to, I was born in Dhaka, and my mother’s ancestral village was far closer) is populated by many poor relatives who barely have any land-holdings to speak of left. People in my family who are economically advantaged all migrated to Dhaka in the 20th century. This migration was enabled by privileges accrued from the past, as we were literate, and had some assets that we could presumably turn into cash to finance a move to Dhaka. But once we got to Dhaka no one cared we were big shit in rural Comilla. Arguably, to a mild extent, we were second-class citizens, being migrants from a rural area, though this is the norm in Dhaka so I don’t think it was a big deal.

The migration to Dhaka from rural Comilla anticipates later migrations, as branches of my family on both my maternal and paternal side reside in the US, UK, Japan, Northern Europe, and the Middle East (with sojourns in Latin America; hi cousin Pablo!). The reason we were able to make these journeys was due to a combination of financial means and educational qualifications. These emerge from our class background. But once in the US, UK, let alone the Middle East, no one gave a shit that we were “Khans.” I am socioeconomically an upper-middle-class American, but that’s not because anyone gave me privileges because I was an “upper-caste Muslim.” Most of the people who were in a position to advance me happen to be white, and to them, I was just another brown person. Perhaps it was even a demerit that I was an “upper-caste Muslim,” since that just meant I was a brown person.

This truth is generalizable. 99% of Americans do not care at all if you are an Iyer or a Mehta or a Reddy. They don’t even know what that means. You are just a brown person to them. Suhag Shukla once told me that when she went to Congress in the 2000’s to lobby for Hindu American rights, hill staff asked if they were “Sunni or Shia.” This is to illustrate that Americans don’t give a shit about what your background is and barely understand it. Malcolm X’s quip about a black man with a Ph.D. isn’t totally applicable, as America isn’t that racist anymore, but it gets to the heart of the fact that in America brown is brown, caste no consideration.

Second, there is the issue that people who are brown in America often do benefit from caste privileges and hierarchy ancestrally. This is a problem and confusion, because it seems obvious, but it gets conflated with the situation in America. The American immigration system is not caste-conscious because Americans barely understand this, but 80% of Hindu Indian Americans are from the 25% of Hindu Indians who are upper-caste. I personally get annoyed with Indian Americans whose families were elite back in India who bring up their stories of discrimination and penury in the US, because their experience is distinct from the social, cultural and human capital they inherit to various degrees from their families. On some level, caste does matter who gets to America, but that is not because the US is caste-conscious, but because Indians are. The US immigration system values particular education and skills that are not equitably distributed among Indians. There are also “push” factors like reservations that mean some upper-caste professionals have far better opportunities abroad, so they leave (this is, for example, a much bigger dynamic in medicine than software engineering, from what I have heard).

Third, the trend now is to argue that Indian caste dynamics are replicating themselves in the US. I don’t think this is true, and I explained why in the UnHerd piece. The minority of Indian Americans raised in the US barely understand what caste is beyond an abstraction. One of the contributors to this weblog proudly asserts their “sudra” status half-seriously, but Indians have told me that usage of that term is somewhat taboo in the subcontinent. The difference here is context, as varna categories are mostly academic, and outside of a few communities (Jats and perhaps, some Patels) jati doesn’t really exist as lived experience. Caste isn’t really a serious matter in America, so who cares if you are a sudra? No one else really does who matters.

It might be somewhat different for the majority of Indians who migrated to the US in the last few decades, as they grew up in a country where caste does matter, and some of their attitudes do replicate. I do assume that most of these people are prejudiced against Muslims and “lower castes” to some degree like the Leftists Indian Americans say (who are usually upper-caste Hindu by background, and so are aware of what things are said “behind the veil”), but these people rarely operationalize their biases because the American racial and social context is totally different from India. When I go to buy alcohol at Indian-owned mini-marts sometimes I get mild third-degree from the owners when they see my last name on the ID, and sometimes it gets to the point I have to tell them I’m an atheist and stop bothering me (this seems a problem during Ramadan in particular, but I often don’t know when it’s Ramadan so don’t blame me). But this is only an inconvenience, and guess what, I can buy alcohol from places without overly curious Indian aunties minding the counter.

Finally, there is the issue of caste discrimination in Silicon Valley, the one place where people argue Indian cultural dynamics are replicating due to the critical mass of immigrants from the subcontinent. People bring up the Cisco case as is if it’s case-closed, but it’s a single case, and the reality is that we don’t really know everything about the dynamics of the case and there’s been no verdict. Believe it or not, not all allegations of discrimination are found to be valid.

But many non-Indians (white people) now routinely tell me there is caste-discrimination in Silicon Valley, this is just a “truth” that is “known.” I’ll be candid that I think some prejudices naturally imbibed from high school, where the caste system is widely taught as constitute to Indians, along with Leftist media narratives about Indian American caste discrimination, are coloring peoples’ perceptions. The reason I wrote the UnHerd piece is that this is becoming the standard narrative and accepted truth for third parties who don’t have any biases or priors on the issue.

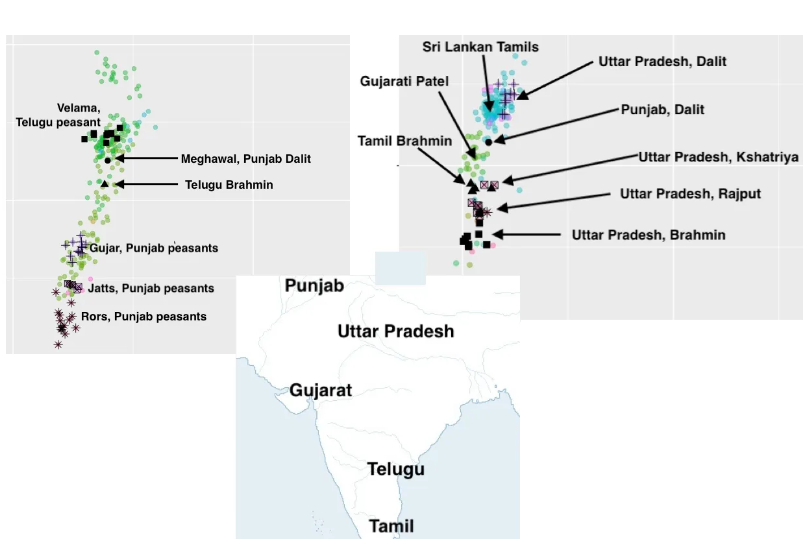

For example, when people say there is pervasive discrimination against Dalits in the Valley, I have to ask, what Dalits? Dalits are 15% of Indians, but 1% of Hindu Indian Americans. It could be possible that this 1% is suffering pervasive discrimination from the non-Dalit majority, 25% of whom are Brahmin and 80% as a whole are upper-caste, but there are opportunities in the US to work for non-Indians who won’t care or know. Indian American society, when it is caste conscious, is overwhelmingly upper-caste and privileged, so they’d have to discriminate against each other!

Yes, there is a level of nepotism and clannishness among Indian Americans, but this is not unique to them. Mark Zuckerburg famously recruited from his dorm and Harvard, and if you are not part of particular elite educational or professional circles you are on the “outside” in the startup world. The same seems true of Indian American entrepreneurs, but their particular ingroup preferences are always reified as “caste.” Though I”ve heard of the “Telugu mafia,” this seems to be the exception, not the rule. And, it is not uncommon for Indian Americans to have some affinity for each other (the majority born and raised in the US still marry Indians), but often this cross-cuts region and caste, rather than reinforcing them.

Additionally, what caste consciousness there is going to be transient. If you are an Indian immigrant to the US, and you are raising children here, there is a 50% chance your grandchildren will have non-Indian ancestry. There is a far lower chance that all four of their grandparents will be from the same jati-varna, in large part because a lot of Indian immigrants themselves are couples in “mixed” marriages (I put the quotations there because in the US Census the marriage of a Tamil Brahmin and a Punjabi Khatri is endogamous).

I will end with an exhortation: the US is a country where you can be reborn anew. Do not buy into the regnant narrative and recreate yourself as a victim. Grasp the world with both hands and make of yourself what you want to be. Some Leftists are trying to replicate Indian dynamics with oppressive upper-castes and oppressed lower-castes in a racial and ethnic context where it’s irrelevant. But some upper-caste Indians are also embracing victim status, whether because they were persecuted in Tamil Nadu (Brahmins), or because they were subject to racial discrimination in the US. I know it’s easy. But I don’t believe it’s the path of honor. Sometimes you do the right thing, even if it’s the harder thing, the socially less acceptable thing. Whatever your caste, religious or regional background, you’re American now. You are now part of a different, great, national project. Make your own narrative, don’t recycle old ones or adopt new ones.