On Substack, Made in China – Does it matter who writes history if no one reads it?

Readers of this weblog care about China. But know too little about it. Become less ignorant.

On Substack, Made in China – Does it matter who writes history if no one reads it?

Readers of this weblog care about China. But know too little about it. Become less ignorant.

BPer Mukunda and I were having a discussion on Twitter, which I want to elevate and push to the blog, because it’s somewhat important.

When I was young (20th century) I read stuff about how the Indo-Aryans described the natives of the subcontinent as dark and “snub-nosed.” That their arrival in some ways was a meeting of two different races.

In the 2000’s I read other books and works that suggested that actually, these descriptions were metaphorical. Terms like “dark” in other words reflect an ideological or tribal conflict, with the descriptions pointing to tropes that signal which side is evil and which side is good. This is not a crazy view. The anthropology is clear that a certain level of fictitious dehumanization occurs with inter-group conflict.

So I accepted this view and moved on with my life.

But in the 2010’s things changed. I am now convinced that 3,000-4,000 years ago a people who resembled what we would term “white” expanded within the Indian subcontinent. If modern Armenians are white, then the Indo-Aryans were white. At least initially. In the subcontinent, they met a variety of people. Some of them, such as in Sindh, were of brownish complexion. Others, to the south and east, would have been considerably darker. I also assume that the Vedas were constructed in situ in the Indian subcontinent. That is, they reflect a milieu of people who were encountering the northwest of the subcontinent, and had recently traversed through BMAC (Indra may actually be a BMAC diety).

What’s the upshot here? I know think that the metaphorical view of the physical descriptions should be set next to the literal view. The reality is probably a mix. But the fact is that groups with very different physical appearances did interact in ancient India. The Aryans were almost certainly very light-skinned, with “sharp features”, in comparison to many of the people they encountered. Though one can construct hybrid scenarios, where Indo-Aryan enemies were described in inaccurate ways precisely because those tropes were associated with tribes and peoples the Indo-Aryans had conquered.

Someone who has deep knowledge of the Vedas in Sanskrit and genetics needs to look into this. That’s obviously not me.

Earlier this week, I had the opportunity to e-attend (over Zoom) a lecture organised by London’s Royal School of Drawing on Indian artists during the Raj. Titled Reflections on Forgotten Masters, the talk by William Dalrymple (the famous Scottish historian) and Xavier Bray (the director of the Wallace Collection) followed the eponymous exhibition organised by the Wallace Collection and co-curated by William Dalrymple last year.

The Wallace Collection is not as well known as other London museums such as the British Museum or the Victoria & Albert Museum. Originally built around the private collections of the nineteenth century British aristocrat Sir Richard Wallace, they have a wide repertoire and organise a number of interesting exhibitions, including on themes related to the subcontinent. I had previously attended their exhibition on Indian medicine titled Ayurvedic Man, which was excellent. Unfortunately the coronavirus pandemic and the ensuing lockdown last year meant that I couldn’t physically visit the Reflection on Forgotten Masters exhibition, and had to view it online.

Continue reading Forgotten Masters: Indian artists during the Raj

Galwan Valley, Pangong Lake, Karakoram Pass, Doklam Plateau, Mishmi Hills. These obscure geographical features and landmarks in the high Himalayas separating India from China have suddenly made their way back into the public consciousness. The catalyst this time is the increased friction between the People’s Republic of China and the Republic of India. I use the phrases “way back” and “this time” deliberately. To scholars and enthusiasts of the Great Game, these names and the surrounding context are eerily familiar: shadow boxing between an ascendant, assertive superpower (Tsarist Russia) trying to throw its weight around in its immediate neighbourhood and an ostensibly weaker but rising middling power (British India) trying to protect its interest in its backyard.

The original Great Game, which played out over the course of the nineteenth century between the British Indian and Russian Empires in South and Central Asia, had all the characteristics of a bestselling novel, filled with action, adventure and intrigue. It also had its set of glamorous characters: Sir Alexander ‘Sikunder’ Burnes- the famous British spy with oodles of charm and dashing good looks to boot- was the James Bond of his era. He was matched on the Russian side by Captain Yan Vitkevich, the enigmatic Polish-Lithuanian orientalist and explorer. Mercifully, there was very little by way of direct bloodshed between the principal protagonists, although things did come close to getting out of hand on a few occasions. No wonder the Russians evocatively called the contest “The Tournament of Shadows”. It was compelling drama and the public- in Britain, India, Russia and beyond- lapped it up. The romance and zeitgeist of the times was captured by the great Victorian author Rudyard Kipling in his famous novel, Kim.

Continue reading The (Original Brown) Pundits: Spies, Explorers and Scholars during the Great Game

Peter Bellwood in First Farmers presents a hypothesis for the expansion of the Dravidian languages into southern India in the late Neolithic through the spread of an agro-pastoralist lifestyle through the western Deccan, pushing southward along the Arabian sea fringe. At the time I was skeptical, but now I am modestly confident that this is close to the reality.

Peter Bellwood in First Farmers presents a hypothesis for the expansion of the Dravidian languages into southern India in the late Neolithic through the spread of an agro-pastoralist lifestyle through the western Deccan, pushing southward along the Arabian sea fringe. At the time I was skeptical, but now I am modestly confident that this is close to the reality.

There is always talk about “steppe” ancestry on this weblog. But there are groups that seem “enriched” from IVC ancestry, as judged by the Indus Periphery samples. The confidence is lower since we don’t have nearly as good a sample coverage…but I think I can pass on what we’ve seen so far: groups in southern Pakistan, non-Brahmin elites in South India, and some Sudra groups in Gujarat and Maharashtra, seem to be relatively enriched for IVC-like ancestry. Then there is the supposed existence of Dravidian toponyms in Sindh, Gujarat, and Maharashtra. And, their total absence in the Gangetic plain.

There have been decades of debate about Brahui. I’ve looked closely at Brahui genetics, and they are no different from the Baloch. Combined with evidence from Y chromosomes (the Baloch and Brahui have some of the highest frequencies of haplogroups found in IVC-related ancient DNA), I doubt the thesis they are medieval intruders (if they are, their distinctive genes were totally replaced).

Genetically, we know that some southern tribes, such as the Pulliyar, have some IVC-related ancestry. But other groups, such as Reddy in Andhra Pradesh, have a lot more. How does this cline emerge? My conjecture is that there were several movements of “Dravidian” people from Sindh and Gujarat into southern India, simultaneous with the expansion of Vedic Aryans to the north into the Gangetic plain. The region the Vedic Aryans intruded upon, Punjab, was not inhabited by Dravidian speakers. Like Mesopotamia, the Indus Valley Civilization was probably multi-lingual, despite broad cultural affinities developed over time.

I was talking to a person of South Indian Brahmin origin today about their genetics. Over the course of the conversation, he showed me Y and mtDNA haplogroup types amongst his jati. The vast majority of the Y haplogroups were not R1a.

I was talking to a person of South Indian Brahmin origin today about their genetics. Over the course of the conversation, he showed me Y and mtDNA haplogroup types amongst his jati. The vast majority of the Y haplogroups were not R1a.

Brahmin groups in India seem to be about 15% to 30% steppe in their overall genome. But their Y chromosomes are usually 50% or so R1a1a-Z93. The lineage associated with Indo-Iranian pastoralists.

So what’s going on with the other haplogroups? For example, J2, L, C, G, and H?

From what I can see J2 and L are the next most frequent haplogroups after R1a1a-Z93. This tells us something. These are haplogroups found in ancient “Indus Periphery” samples. And, these two haplogroups are found at high concentrations in the northwest of the subcontinent.

It doesn’t take a {{{Brahmin}}} to connect the dots here. Some of the gotra as early as the Vedic period were almost certainly derived from high-status individuals in the post-IVC society. Warriors and priests in the fallen civilization of the IVC, which had likely degraded itself to a level of barbarism by the time the Indo-Aryans became ascendant.

I like to make jokes about “sons of Indra.” But let’s give the dasyu credit where it’s due: those Indians carrying J2 and L almost certainly descend from the men who build the great cities of yore. Their dominion was lost when their civilization fell, but they integrated themselves into the new order.

What is the difference between introspection and self-hatred? Introspection brings reflection, intention, and evolution. Self-hatred brings rumination, doubt, and rot. One is essential, the other is extinction.

Engagement of either shift one’s fate. From the roots of mentality grow branches of thought, blooming into flowers of action and eventually the fruits of result. Nowhere is this more clear than the night and day of the Indian elite.

The ancient elites of India wrote eternal tomes of meditation that built the bedrock of a civilization that has seen the best and worst of humanity, outlasting every peer and power. Their art and literature emanated confidence, beauty, and advancement. While sure of themselves, they had no qualms integrating new ideas from abroad or from home. Diversity was strength, and challenge was opportunity.

Their descendants today are devolution incarnate – Kali Yuga realized. An unending anguish for the approval of outsiders, self-flagellating of even the most innocent of traditions, and an obsessive compulsion for mediocrity are the trickle-down that these elites have given Indians since independence.

While trivial bashing of them is enjoyable, I want to get to the meat of their minds as well as what these minds have yielded.

What causes the exceptional self-loathing of these elites? The mania of knee-bending and the need to constantly look outwards for validation? The ability to be stupendously arrogant towards their birthright to rule yet despise their roots? Continue reading The Self-Hating Prophecy of Indian Elites

25% of humans live in the Indian subcontinent. 18.5% live in China. Together that’s 43.5% of the world’s population in the two great Asian civilizations. Not a trivial number in the 21st century, especially in a nascent multipolar world.

25% of humans live in the Indian subcontinent. 18.5% live in China. Together that’s 43.5% of the world’s population in the two great Asian civilizations. Not a trivial number in the 21st century, especially in a nascent multipolar world.

And yet the two societies often lack a deep awareness of each other, as opposed to an almost pathological fixation on the West, and in India’s case the world of Islam.

Indians are clearly geopolitically aware of China. Obsessed even. But aside from cultural exotica (e.g., the Chinese “eat everything”), there seems to be profound ignorance.

This is illustrated most clearly when I hear Indian intellectuals aver the proud continuous paganness of their civilization. Setting aside what “pagan” means, and its applicability to the Hindu religious tradition, the key here is a contrast with the world to the west, which was impacted by a great rupture. The people of Iraq have a written history that goes back 5,000 years, but the continuity between ancient and modern people of the region is culturally minimal. Modern inhabitants of Bagdhad know on some level that their ancestors were Sumerian, but for most of them their identity is wrapped up in their religion and the lives of the Prophet and his family, or for Christians that of Jesus.

This is illustrated most clearly when I hear Indian intellectuals aver the proud continuous paganness of their civilization. Setting aside what “pagan” means, and its applicability to the Hindu religious tradition, the key here is a contrast with the world to the west, which was impacted by a great rupture. The people of Iraq have a written history that goes back 5,000 years, but the continuity between ancient and modern people of the region is culturally minimal. Modern inhabitants of Bagdhad know on some level that their ancestors were Sumerian, but for most of them their identity is wrapped up in their religion and the lives of the Prophet and his family, or for Christians that of Jesus.

This is not the case with the majority of Indian subcontinental people, whose religious traditions and cultural memory go back further, literally to the Bronze Age at the latest. The foundational mythological cycles which define Indian culture probably date to 1000 to 1500 BC. During this time Kassites ruled Babylonia, and the Assyrians were coming into their own. Until modern archaeology, these people were only names in the Bible or in Greek historians.

But this is not only true of India. These Chinese also look to the Bronze Age Shang dynasty, and in particular, the liminal Zhou, to set the terms of their modern culture. The ancient sage kings, who likely predate the Shang, are also held in cultural esteem.

Does any of this matter? I don’t honestly know. I’m American, not India or Chinese. But perhaps it might help on some level if these two civilization-states could understand and accept that they share in common having extremely deep cultural roots apart from the revelation of the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob.

There is some discussion on “Hindu Twitter” and elsewhere about the French response to the murder of Samuel Paty. In short, France is going “medieval” on the asses of a lot of Muslims, even nonviolent but very conservative organizations. To use a German phrase, the French state is entering into a Kulturkampf against militant Islam. Or at least it is signaling that it is.

There is some discussion on “Hindu Twitter” and elsewhere about the French response to the murder of Samuel Paty. In short, France is going “medieval” on the asses of a lot of Muslims, even nonviolent but very conservative organizations. To use a German phrase, the French state is entering into a Kulturkampf against militant Islam. Or at least it is signaling that it is.

To all this, some on the Hindu Right are asking why some liberal or Left intellectuals are applauding or tolerating France’s reaction, which is hitting down hard on the Muslim community. Would they be so tolerant of India clamping down on Muslims? My own answer is simple: different nations have different histories, and abstract universal values and standards are often not useful.

One writer who caused an evolution of my thought is the fiery Nassim Nicholas Taleb. His brash yet precise style, swashbuckling smashing of intellectuals, and ancestral Mediterranean insights provided an alternative thought diet in a world that force-feeds the same message to me on television, social media, and amongst my friends here in a buffet of American coastal elites. From the jest of randomness, the beauty of black swans, the advancement of antifragility, and piercing skin in the game, Taleb created a dancing sequence of jabs and hooks to create a battle-hardened mentality to approach the world and knowledge.

One of the biggest yet most nuanced lessons I learned from Taleb was that of scale – how inputs yield outputs differently, depending on size and magnitude. An easy example of this common-sense concept is the difficulty in enforcing an exercise and diet regimen for oneself versus one’s entire family versus one’s entire community and so on. Trying to do good things is easier and possibly more effective in the long run when done on a smaller scale.

It’s one thing to change oneself on an individual level, another to create a visible shift in societies, and another to execute proper governance accounting for different groups along with the externalities and the headaches that come along with policies.

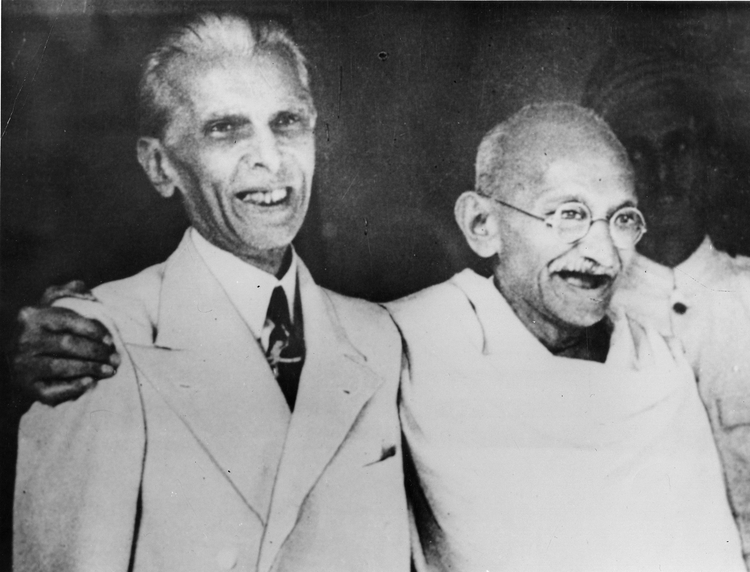

Satyagraha or the holding of truth paved the road in Mahatma Gandhi’s non-violent struggle for India’s independence. Inspired by the ahimsa of Hinduism and Jainism, Gandhi brought his own interpretation taking an ancient concept to new frontiers.

The principles of satyagraha:

Admirable qualities that built the legend of the Mahatma, the great soul. Selflessness at its apex captured the hearts of Indians across the subcontinent in a mass non-violent movement at such a scale that it has no parallels in world history before or since. While an individual taking on satyagraha is highly laudable, expanding it to society proved a double-edged sword.

With the British reeled from a cataclysmic World War at home and a cracking crown jewel in the Raj, their leaders eventually acquiesced to the rightful demands of an independent India. Truth had met victory in the eyes of the Mahatma’s disciples, but this satyagraha would now face a much older foe that had made its home in the subcontinent over centuries.

Naiveté crept into a population until it was maimed by the madness of a maniac with Muhammed Ali Jinnah’s call of “Direct Action” severing the dreams of Gandhi and millions of other Indians for a united India. What Gandhi and his ideological descendants, Gandhians, got wrong is how values apply at scale. Stunningly noble principles for individuals could not be forced upon a people who were facing a polar opposite ideology filled with aggressive malice and cultivated by despicable men to match.

“Hindus should never be angry against the Muslims even if the latter might make up their minds to undo even their existence.” —Mahatma Gandhi, Birla Mandir, New Delhi, on April 6, 1947; Partition Would Occur 4 Months Later

The beauty of satyagraha was smeared with the ugliness of Islamism and this duality incarnated by way of a bloody partition. An assassin would cite the suicidal idealism of Gandhi as the gunpowder to his fatal and fateful bullet that transformed a man into a martyr and Gandhi into a god. The last breath of Gandhi permeated throughout Indian politics since.

Forsaking looking at others’ faults and focusing on your own to improve are great actions on an individual level. Trying to apply this mentality at a large scale is impossible and can be disastrous. Gandhi’s goal to apply the kindness and tolerance that he practiced throughout his life at a larger level provides a testament to the dangers of this ruinously beautiful ideal.

While I may have been harsh on Gandhi, his satyagraha was a very inspirational movement that achieved its primary aim (with the help of several violently resisting Indians of course, too) and would echo in the minds of different generations and geographies. Its failures would only truly come to fore when reciprocity broke down as scale increased and satyagraha faced the sinister.

A communal concoction that had been boiling for centuries spilled over once again just as Gandhi tried to ease the concerns of an ambitious Jinnah and company who were decided in their choice to break India. What went so wrong here?

Good behavior scales badly. Bad behavior scales goodly.

An essential lesson to impart here is that the kindness that we should all so admire shouldn’t be extended frivolously in the world at large scales. Strive to be exceedingly kind to all the individuals in your life, but expect less of a return as familiarity decreases and quantity increases. The world of geopolitics and governance is witness to how might towers over magnanimity as scale maximizes. And it is here where we need to examine a powerful chapter across world history for the past several decades – social justice.

Social justice has yielded some of the greatest moments in politics as policies such as apartheid and segregation were thrown into the abyss, while reservations in India helped lower castes climb out of the abyss. Tangible benefits were born through simple and actionable policies and goals.

Today, however, social justice movements have been plagued by vague goals and a lack of dynamic leadership. Faceless protests descend into rioting at an alarming rate with politicians taking advantage of the chaos and righteous movements thwarted by themselves. No Gandhi’s, no Dr. King’s, no Mandela’s lead the wave of change today. The absence of these emissaries who create a dialogue between the masses and politicians means that when social justice is applied at scale, it descends into disarray with vultures disguised as politicians picking and prodding at a soon to be carcass of a movement. Justice has inherent danger when applied at scale and needs the right leaders and values to guide it properly.

On the flip side, there are also the potential horrors of hyper-local justice such as in the panchayat system of rural India, where a clan of elders decides the fate of the accused, sometimes with cruel and Hammurabi style punishments. We are seeing this hyper-local eye for an eye type justice now extrapolate to larger scales amongst many intelligentsia and political leaders, a notion that would lead to disastrous strife if the scale continues to ramp up.

Bruno Maçães, a prominent political analyst and now part-time philosopher, proposes that America is entering a period where fantasy supersedes reality. The digital world at your fingertips is shaped by the hand of technology. What you see and consume on your timeline is a lens with a distorted scale of the world. What is anecdote becomes amplified into annals as the speed of the extreme races past the mundane on the information superhighway.

Outrage oscillates the Overton Window wildly as technology’s reality distortion field melds our perception. This pendulum pushes our politics in an increasingly divisive direction as upstart politicians wield clout and clicks on social media steering agendas into fantastical territories that are disconnected from realities and history. Technology and social media have brought notions of the past closer to us than ever as rabid battles over who oppressed who pan out in the digital theatre of war.

Elite consensus is upended by guerrilla historians, sometimes erroneously but many times rightfully. These intellectual insurgents zoom out and in on specific instances to promote their perspective, occasionally out-of-context but every so often right on the money. The thin selection of stories published by establishments has given way to an explosion of untold chapters bypassing traditional media and academia, all with the help of technology.

However, this has directly lead to an exacerbation of the application of justice. Crimes of the past are scaled out to include those in the present. Justice morphs into its fraternal twin, revenge. Now, I don’t believe it’s right to silence the discussion of the horrors of the past as that is essential to reconciliation. However, this discussion must be joined with efforts to bring real justice – opportunity and truth – to those who have been oppressed and not extend the hatred of the past to the descendants of oppressors in the present. Funny enough, the answer to opportunity may lie in economics (whether welfare reform, access to capital, ease of business, tackling inequalities, etc…) rather than culture wars.

Today’s society values performatives over pragmatism. In the quest to fight historical injustices, we can’t ask for revenge that spirals into a wheel of fire. We should remember the great effort to organize mass non-violent movements such as satyagraha and civil rights in an era today where the embers of violence quickly follow the gasoline rhetoric of many of our politicians and “activists.” For only great men, great women, and great movements transcend the limits of scale and sculpt our tomorrow.