the Portuguese in Goa, Madurai & Asia

He wrote in the Tamil language works in which the Hindu wisdom and the Christian were brought into harmony. He composed Christian poems which resembled the ancient Vedic hymns. He allowed his Brahman converts to continue wearing the sacred thread and to celebrate certain Hindu feasts; in the school which he opened, he allowed pagan rites to be continued and he respected Hindu prejudices over caste; he allowed no outcaste to touch his person, and if he needed to administer the sacrament to a member of an inferior caste, he proffered the Host at the end of a little stick.

I’ve typed out some fascinating excerpts from the Book “The Reformation” by Owen Chadwick. I was so stunned when I typed out the paragraph above that I put it to the top of the post.

I’ll excerpt more paragraphs from the book in future posts but I’m posting what I’ve typed out now.

Especially intriguing is how the Brahmins of Madurai accepted a Portuguese missionary as one of their own; it lends idea to the fluidity of the caste system if you were foreign.

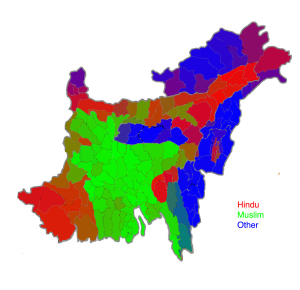

The colour basis of caste seems almost irrefutable since the incidents I touch on took place in Madurai, which endured only 150 years of Muslim rule.

If there had been no Islam all the Turkic invaders would have been absorbed into a Hindu framework like the pre-Islamic invaders.

Japan

Even though I haven’t typed out anything about Japan in this post I’ll excerpt one quote. ‘In ten years,’ wrote a sanguine missionary in 1577, ‘all Japan will be Christian if we have enough missionaries.’…..

From 1627 suspects were forced to muddy with their feet a picture of Christ or the Virgin…..

The Portuguese

While the Spanish were at work in the Americas, the Portuguese were moving eastward. Their progress is traceable by the foundation of new sees: Madeira 1514, Cape Verde 1532; Goa, which became the seat of the viceroy in the far eastern empire, 1544, and an archbishopric from 1558…… the Jesuit Bendetic de Does crossed the Khyber pass disguised as an Armenian merchant and journeyed through Afghanistan and over the Hindu-Kush into Chinese Turkestan, to die at Suchow in China.

The Portuguese missions had many deficiencies, but they lacked neither courage nor enterprise. They were less conscious of a colour bar than other Europeans.

The Portuguese in the East were facing a different problem. They were weaker than the Spanish, and were meeting civilizations and religions far stronger than those of Inca and Aztec.

The size of the task was not at first understood. In some places in the East the pace of conversion was as rapid as in the Americas. In the Philippines the Spaniards achieved the outstanding success of all the eastern missions: 400,000 converts by 1585, about two million by 1620. Manila was founded in 1571, had a bishop from 1579, an archbishop from 1595, a Dominican university from 1619. It was natural that expectations everywhere should be sanguine.

Francis Xavier from Goa to (Cape Comorin) Kanyakumari

He embarked from Lisbon in 1541 with three companions as the Pope’s Vicar for all the coasts of the Indian ocean, and he had support from the King of Portugal (all Portuguese officials were ordered to support him).

A plain-speaking aristocrat, equally comfortable in a south German court, he went to Goa. From Goa, where he found a bishop, a cathedral, convents, and numerous churches already flourishing, he moved to Travancore, thence to Malacca and the Malay peninsula, thence to Amboina, and back to Travancore. In 1549 he sailed from Goa to Japan, accredited with letters to the sovereign. After preaching in the streets or disputing with the monks for two years, he determined to convert China as a preliminary to converting Japan. To secure the requisite authority he returned to Goa. But he found it difficult to get further than Singapore, tried to smuggle himself into Canton, and died on the Chinese coast near Macao late in 1552….

‘All things to all men’ was a motto familiar to Xavier who rapidly felt himself at home and at ease among Hindus or Muslims or Japanese..

He followed the method of mass conversion. On the fishers’ coast near Cape Comorin he wandered from village to village accompanied by his interpreters. He would gather the villagers together by ringing a handbell, and recite the creed, and the Lord’s Prayer, the Ten Commandments, and the Hail Mary, which had already been translated into Tamil. When the audience, after a few days or weeks, had sufficiently learnt the words and professed their belief in the articles of the creed, he baptized them, and went on baptizing until his hands sank with exhaustion……

It was extraordinary that a single man should have succeeded in opening so many doors.

The Problem of the Great Religions

In the East the evangelists confrontered a task of which the American missions knew nothing – the great religions. The Jesuits, who in 1579 went to the court of the Great Mogul, Akbar, found that their Christian worship was acceptable in the temple which he had built at Fatehpur-Sikhri, but they must share the building with Parsees, Hindus, Jains and Buddhists.

Christian Iconoclasm and the destruction of Buddha’s tooth in Goa

An alleged tooth of the Buddha was brought to Goa in 1560, and thought a bankrupt government wanted to accept an offer of £100,000 from a rajah, the archbishop stepped in to destroy the relic.

The Spaniards in America and in the Philippines followed the principle that all the old religions must be destroyed as being heathen, that thus the new might enter in all its purity. The Bishop of Manila in the Philippines forced the Chinese converts to cut off their queues and wear their hair like the Spaniards, as a visible sign that they were freed from heathenish customs. ‘I longed,’ wrote the Jesuit Vilela in 1571, after he had seen the worshippers dancing at the Shinto shrine of Kasuga in Japan, ‘I long to have had a second Elijah there to do what he did to the priests of Baal.’

But in the religious circumstances of India and China, this Hebraic and exclusive tradition within Christendom began for the first time to be challenged or modified………..

Goan Christanity:

As the other religions became better know, the question of practise became crucial. The Spanish had hardly been troubled; they discouraged all old practises, and turned their converts, not only into Christians, but into Spaniards. The Portuguese tried the same policy in Goa. The original Portuguese catechism for India translated the question ‘Do you want to become a Christian?’ as ‘Do you want to join the caste of the Europeans?’ But the policy was soon found impossible, and their missionaries must therefore decide which of the social customs of Japanese, Chinese, or Indian was merely social and civil, which were religious but capable of a Christian meaning, and which were incompatible with receiving baptism.

In China reverence for ancestors and in India caste was integral to the social system……

The Christian Brahmins of Madurai

The example of Ricci’s method of evangelism was followed with resounding success by two Jesuits, Alexander de Rhodes in Indochina and Robert de Nobili in South India.

From 1606 Nobili conducted a mission at Madurai. He had himself taught by a Sannyasi, a penitent of the Brahman caste, dressed himself in the saffron robe of the Brahman ascetic, shaved his head and wore earrings, lived as a hermit in a turf hut upon a vegetarian diet. The Brahmans began to admire him as a holy man, and ended by recognising him as one of themselves.

He wrote in the Tamil language works in which the Hindu wisdom and the Christian were brought into harmony. He composed Christian poems which resembled the ancient Vedic hymns. He allowed his Brahman converts to continue wearing the sacred thread and to celebrate certain Hindu feasts; in the school which he opened, he allowed pagan rites to be continued and he respected Hindu prejudices over caste; he allowed no outcaste to touch his person, and if he needed to administer the sacrament to a member of an inferior caste, he proffered the Host at the end of a little stick.

It is not surprising that some of his fellow Europeans were shocked, and a long succession of denunciations went back to Rome. In 1618 he was brought before the court of the Archbishop of Goa and astounded the court by appearing in the garb of a Brahman ascetic. ‘The case of the Malabar rites’ was referred to Rome. In 1623 Rome refused to condemn Nobili, ’till further information was available’ and he continued to extend this unusual and successful evangelism until there were twenty-six Brahman converts among the 4,000 Christians of Madurai.