Last year marked the 280th anniversary of Nadir Shah’s invasion of the city of Delhi – an event as catastrophic as the invasion of the city by Timur in 1398.

It is worth reflecting on this remarkable event in early 18th century – an episode that underscores the perils of a weak state.

Source : wiki images

State of the Empire in the 1730s

What’s remarkable about this invasion is that it happened barely 32 years after the death of Aurangzeb in 1707 – a time when the Mughal Empire was still very formidable and pan Indian in extent (albeit a tad over-extended). By 1739, the decline of the empire was well underway. The Mughal emperor at the time of Nadir Shah’s assault was Muhammad Shah, Aurangzeb’s great grandson.

Now it is well known that Aurangzeb was just the 6th Mughal emperor, between 1526 and 1707. But Muhammad Shah who ascended the throne in 1719, was the 12th!

So you had six new emperors in the ten years following Aurangazeb’s death – as many emperors as the number between 1526 and 1707 – a commentary on the chaos at the head of the empire in the years succeeding Aurangzeb.

Now let us do a quick summary on the state of the region just before Nadir Shah’s assault –

- Bengal was already semi-independent, with Murshid Quli Khan becoming the first Nawab of the region circa 1720.

- Avadh was on its way to autonomy with Saadat Khan becoming its first Nawab in 1722.

- The Marathas were clearly in the ascendant. By 1737, they had gained tax collection rights in Deccan, Gujarat, Bundelkhand. In 1737, two years before Nadir Shah’s raid, Baji Rao attacked Delhi and scored a remarkable victory – despite having an army half as large as the Mughals. Post the battle of Delhi, Malwa was ceded by the Mughals to Baji Rao’s Marathas. In 1738 on the eve of the Nadir Shah invasion, the Mughal crown was already weakened considerably.

The other point to note is that even after 2 full centuries of Mughal rule, the nobility of the land was largely foreign born. So power was wielded by men who felt no patriotism for India, and had no affinity to the traditions and culture of the land. Let’s take some examples –

-

-

- Nizam Ul Mulk, perhaps the most influential noble in early 1700s, was of Uzbek ancestry. His grandfather had migrated from Samarkhand

- Saadat Khan, the Nawab Avadh, was a native of Nishapur (north eastern Iran), who had moved to India in early 1700s

This goes contrary to the perception pushed by many historians today that Mughals shouldn’t be regarded as foreigners as they were “thoroughly assimilated” and “rooted” in the Indian soil. Hardly the case.

The foreign origins of much of the creme-de-la-creme of the nobility meant a somewhat weak affinity to the land, and susceptibility to treason against the state. Saadat Khan in fact later advised Nadir Shah to assault Delhi, and ask for a large ransom.

Now let’s examine the situation in Persia in the decades leading up to Nadir Shah’s invasion of India.

The Safavid empire ended in 1722 following an Afghan rebellion. But this proved shortlived, with Nadir Shah defeating the Afghans and establishing his rule over Persia starting 1736.

With respect to Afghanistan – Mughals had lost Southern Afghanistan (including Qandahar) to Persia in the mid 1600s. However they retained control of Kabul / northern parts of the country.

Right from the start of his reign, Nadir evinced great interest in the Mughal Empire. He could see the waning power in Delhi as an opportunity. Also the Persian hold over Qandahar meant a strategic advantage for Persia, lost to the Mughals for nearly a century.

Failed Diplomatic efforts

What’s interesting though is that Nadir didn’t simply launch an assault on India with a savage horde. He engaged in extensive diplomacy, with multiple communications with Mughal crown!

E.g. in 1736, Nadir Shah sent an envoy to Delhi, informing of his intent to expel Afghan rebels from Qandahar, and requesting that the Mughal power in Kabul should obstruct these Afghans and not give them refuge. The Mughal emperor Muhammad Shah responded agreeably. But when the expulsion of Afghans happened from Qandahar in early 1737, the Afghan rebels did flee to Kabul. The Mughals breached on their promise!

When Nadir Shah sought an explanation for this breach through an envoy, Delhi gave him no reply. And on top of that detained the Persian envoy!

Even communication between Delhi and Kabul was terribly slothful! When the Mughal governor in Kabul sought funds for his troops, his repeated requests were turned down by Muhammad Shah the emperor. So clearly you had a situation when the frontier regions of Afghanistan and Punjab grew gradually defenceless through neglect, at a time when Persian power under Nadir Shah was on the rise.

This was an empire waiting to be assaulted.

The Battle at Karnal

Nadir conquered Northern Afghanistan in 1738. Peshawar and Lahore soon followed. Then the Shah marched to Karnal, where a decisive battle awaited him. In the great battle that ensued at Karnal (February 1739), the Persian army numbered at 55K cavalry. The Mughal army was likely larger, but heavily reliant on elephants – a ponderous and outmoded carrier.

What’s also remarkable is that the Mughal armies took for ever to assemble at Karnal! Saadat Khan, the noble from Awadh, took a whole month to arrive with his troops in Karnal.

It took him 3 days to travel from Delhi to Panipat – a mere distance of 55 miles! This is in sharp contrast to the blitzkrieg raids that Marathas were undertaking elsewhere in India at the same time. The Mughal army (in part perhaps because of its reliance on elephants) was not mobile enough. Not nimble enough.

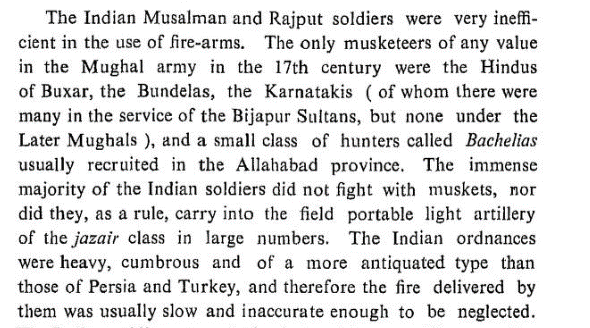

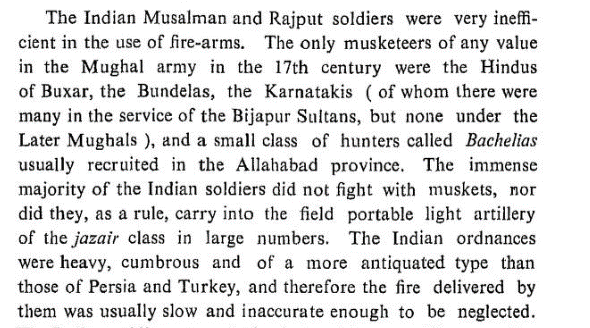

The other major difference was in the familiarity and comfort with fire-arms. The Persian army revelled at fire-arms. The Mughal army still relied a great deal on swordsmanship and “felt a contempt for missile weapons” (to quote Jadunath Sarkar)

Here’s Sarkar elaborating on the Indian inefficiency at fire-arms

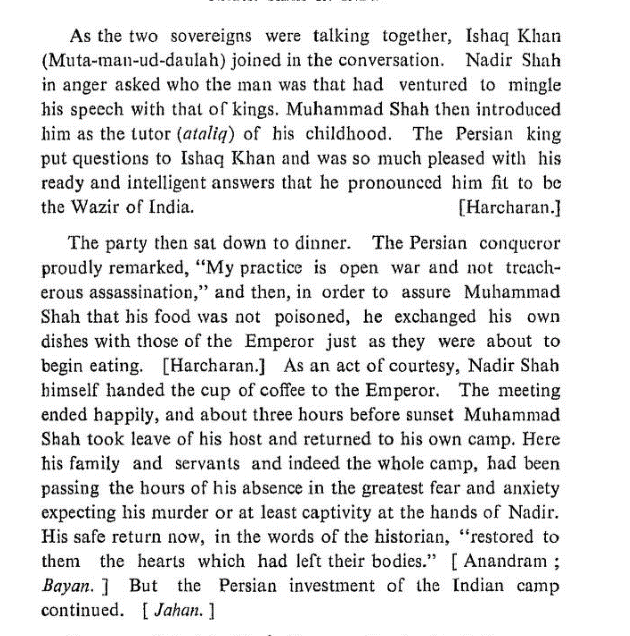

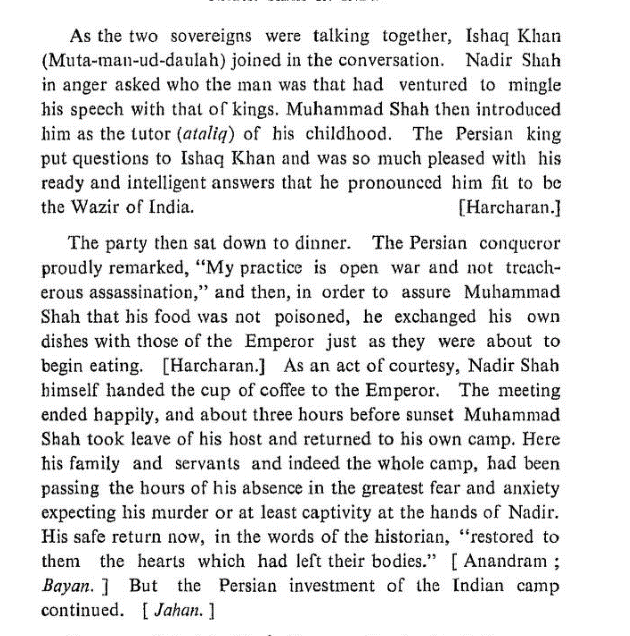

So the result at Karnal was a resounding victory for Nadir Shah. But what followed was not a raid on Delhi rightaway, but extensive negotiations for peace! This included face-to-face conversations between Nadir Shah and the Mughal emperor Muhammad Shah at the Persian camp near Karnal.

Negotiations post battle

Here’s an account from Sarkar drawing on the primary sources of Harcharan, Anandram et al on the first meeting between Nadir Shah and Muhammad Shah.

But the emperor reneged on his word and did not pay the requested ransom of Rs 20 crores! This angered Shah and eventually led to a second meeting with the emperor and the latter’s house-arrest

Raid on Delhi

What followed was the famous raid on Delhi, which lasted about 50 days. But a point to note is that the provocation for this trigger came from the Mughal side. Saadat Khan in particular – the Nawab of Oudh. While Nadir originally had an indemnity of 50 lacs in mind, it was Saadat who told Nadir after the Karnal battle, that if he were to go to Delhi, he could get 20 crores! As opposed to 50 lacs.

Nadir’s raid on Delhi was focused mainly on collection of ransom. Not just from the treasury, but also from private mohallas, with the consent of the Mughal emperor. But he did not intend to engage in a massacre. What triggered the massacre was an uprising in Delhi against the stationed Persian soldiers. Some 3000 Persian soldiers were killed by Delhi-ites. Nadir had to retaliate with a massacre, which likely claimed some 20K Delhi civilian lives in a span of a few hours. This is a conservative estimate, with other estimates as high as 4 lacs.

Consequences and Takeaways

So that brings us to the end of this brief account of Nadir Shah’s raid of Delhi. What were its consequences?

First of all the raid did not trigger the empire’s decline per se. The Mughal empire’s decline had started long before Nadir Shah set foot. But Nadir Shah’s invasion unlike Timur had some political consequences – it resulted in the loss of Afghanistan and the modern Frontier province to Persia. Eventually it led to the loss of Punjab to the Afghans (under Ahmed Shah Abdali) a few decades later. The Maratha raids on Bengal too ensued a few years after Nadir’s raid.

So it could be said that Nadir Shah’s invasion hastened the decline of the empire, though not necessarily the cause of it.

More importantly it has some lessons for our times. We tend to think of “invaders” as ravaging hordes lacking in civilization and human values. But Nadir was a shrewd diplomat. He engaged in multiple diplomatic overtures, though the Mughals bungled every one of them. Even the ransom amount to him was suggested by a Mughal insider, Saadat Khan. So was the idea to raid Delhi. Even the massacre at Delhi that ensued was in large measure a retaliation of the massacre of his own soldiers by Delhi civilians

We live in an age of constitutional patriotism, where deference to the state has to transcend ethnic ties. But Nadir Shah’s episode has lessons for us in this respect.

The reason the invasion was facilitated was because of high treason, which in turn was caused by the fact that much of the Mughal nobility was of foreign origin, and felt little patriotism towards India.

Some 30 years ago, there was a debate in India around “Foreign origin” of Sonia Gandhi and whether this should bar her from public office and electoral politics. The debate settled in Sonia’s favor

But then when we reflect on episodes like these from the past (Saadat Khan’s treason for instance), you wonder if an ethnic connect to the land is a pre-requisite to expect a high degree of patriotism.

We will conclude on that note.

References: Jadunath Sarkar’s “Nadir Shah in India”.

The author tweets @shrikanth_krish

There is some discussion on “Hindu Twitter” and elsewhere about the French response to the murder of Samuel Paty. In short, France is going “medieval” on the asses of a lot of Muslims, even nonviolent but very conservative organizations. To use a German phrase, the French state is entering into a Kulturkampf against militant Islam. Or at least it is signaling that it is.

There is some discussion on “Hindu Twitter” and elsewhere about the French response to the murder of Samuel Paty. In short, France is going “medieval” on the asses of a lot of Muslims, even nonviolent but very conservative organizations. To use a German phrase, the French state is entering into a Kulturkampf against militant Islam. Or at least it is signaling that it is.