In view of increasing friction between civil and military leaders in Pakistan (again), may be a good time to reminisce about the anniversary of 1999 coup. This piece was written in 2012. I’m no wiser in 2016. Enjoy.

“We expect men to be wrong about the most important changes through which they live.” Harold Lasswel

Hamid

Count Down – October 12, 1999

Hamid Hussain

“After this operation, it’s going to be either a Court Martial or Martial Law!” Assistant Chief of Air Staff (Operations) Air Commodore Abid Rao after attending a briefing at X Corps Headquarters about Kargil operation, May 1999 (1)

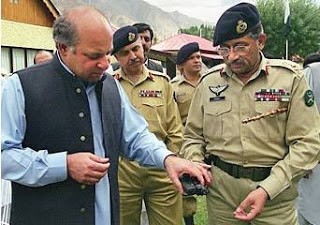

On October 12, 1999, Pakistan army moved to remove Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif’s government when he announced pre mature retirement of Chief of Army Staff (COAS) General Pervez Mussharraf. Different versions of events were later provided by active participants as well as bystanders. Later, many also gave a revisionist account of the events. This article will review the back ground of differences between Nawaz Sharif and Mussharraf that led to fateful decisions of these two key players and events of October 12.

In the fall of 1998, Nawaz Sharif could not be blamed for feeling very confident and on top of his game. Sharif’s government’s two third majority in the Parliament, repeal of eighth constitutional amendment taking away the power from the president to dissolve national assembly, removal of Chief Justice, resignation of president Farooq Ahmad Khan Leghari, appointment of a Sharif family protégé, Rafique Ahmad Tarar as president and resignation of COAS General Jahangir Karamat had decisively shifted the balance in favor of the prime minister.

Two important events started the gulf between civilian and military leaders; resignation of COAS General Jahangir Karamat in October 1998 and Pakistan army’s operation across Line of Control (LOC) in Kargil in the spring of 1999. In October 1998, COAS General Jahangir Karamat resigned few months before completing his term due to differences with Sharif. There was deep resentment among the officer corps on this issue. Sharif picked Mussharraf as COAS superseding Chief of General Staff (CGS) Lieutenant General Ali Quli Khan and Quarter Master General (QMG) Lieutenant General Khalid Nawaz Malik. In some cases, new army chief makes slow changes of the top tier while in other cases, whole new team of close confidants is brought in quickly. Mussharraf embarked on major changes and brought the new team of his own confidants to key positions of command of Rawalpindi, Multan, Lahore and Karachi Corps and CGS, MS and DGMI posts (Lieutenant General Muzzaffar Usmani was brought from Bahawalpur Corps to important Karachi Corps while Lieutenant General Salim Haider was shifted from Rawalpindi Corps to Mangla Corps).

There was no history of any problem between Mussharraf and Lieutenant General Khawaja Ziauddin. Ziauddin was from Engineers Corps and their paths have not crossed during their professional career. In fact, immediately after the announcement of his appointment, when Mussharraf settled down in Armor Mess (General Karamat was still in Amy House) and started shuffling the senior brass, Ziauddin then serving as Adjutant General (AG) was with him. Two days later, Sharif announced appointment of Lieutenant General Khawaja Ziauddin as Director General Inter Services Intelligence (DGISI) without consulting with Mussharraf.

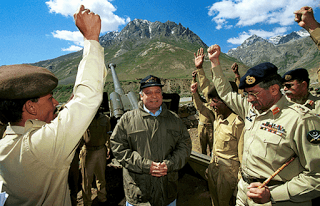

In the spring of 1999, a small group of senior officers were involved in the decision of sending Pakistani troops across the LOC in Kargil area of Kashmir, starting a flare up that quickly got out of control of Pakistani decision makers. Initially, Pakistan refused to acknowledge the presence of its troops across the LOC but later after vigorous response from Indian armed forces and amid international condemnation was forced to withdraw. There was outcry in the country and civilian and military leadership got entangled in the blame game.

Sharif shifted the blame on the army brass and took the position that army had not fully briefed him about the extent of the operation. Army brass on its part, now wanted the civilian leaders to take the blame for the humiliating withdrawal of the troops. All was not well in the army and there was significant resentment among the officer corps. General Mussharraf toured various formations where he was confronted with harsh questions from junior officers. (2) Mussharraf shifted the blame on Sharif government by stating that civilian government was responsible for the decision of withdrawal and armed forces were bound to obey it.

Initially, differences between Sharif and Mussharraf were over minor issues. Sharif removed retired Lieutenant General Moinuddin Haider from the post of Governor of Sindh province. Haider was senior but had friendship with Mussharraf (later Mussharraf appointed him interior minister). Sharif asked Mussharraf to sack two Major Generals; Anis Ahmad Bajwa and Shujaat Ali Khan, accusing them of working against him. Bajwa was Vice Chief of General Staff (VCGS) and fully supported his Chief during Kargil crisis. Shujaat served as director of internal security wing of ISI. This section usually deals with the domestic political scene and gets entangled in the palace intrigues. Mussharraf refused to oblige Sharif on this issue. After the coup, Mussharraf appointed Bajwa his Chief of Staff (COS) and Shujaat was appointed ambassador to Morocco.

After Kargil crisis, gulf between Sharif and Mussharraf widened and both parties started to strengthen their positions. In mid-September at Corps Commander’s Conference, Mussharraf asked his senior officers the question of competency of Nawaz Sharif. While all Corps Commanders agreed that his performance was not good but expressed their view that they could not remove him without a reasonable cause. Mussharraf then brought the issue of what if Sharif tried to sack him? The military brass agreed that they would not allow that. (3) There was now consensus that army will not allow two army chiefs to be removed prematurely.

As the mistrust and suspicion between Sharif and Mussharraf escalated, both sides started to make their moves. Sharif only had the executive power to replace Mussharraf but he had to move silently and stealthily to achieve his aim. (4) He also thought that a warning from Washington to the military brass may also help to strengthen his hand. General Mussharraf’s power base was military and he started to consolidate his position. His biggest advantage was general resentment in armed forces after forced resignation of previous COAS. In addition, he successfully deflected the resentment and anger of junior officers about planning and execution of Kargil operation by suggesting that plan was good but it was the civilian leadership that had succumbed to pressure and ordered withdrawal.

Mussharraf was not sure about two Corps Commanders; Lieutenant General Tariq Pervez of Quetta based XII Corps and Lieutenant General Salim Haider of Mangla based I Corps. In late September 1999, he replaced Haider by promoting Director General Military Operations (DGMO) Major General Tauqir Zia to Lieutenant General rank and bringing him to command Mangla Corps. Haider was given the post of Master General of Ordnance (MGO); a staff position with no direct control of troops. Tariq Pervez’s cousin Nadir Pervez was member of Sharif cabinet and Mussharraf thought that Tariq was passing information about decisions at Corps Commanders meeting to Sharif through his cousin. It is alleged that Tariq Pervez had warned Sharif about the consensus of the senior army brass that if Mussharraf was sacked, the army will take over. Later, Mussharraf accused Tariq Pervez of ill-discipline and ‘plotting against me’. (5) Tariq Pervez had criticized the planning and execution of Kargil operation at Corps Commanders meeting and Mussharraf interpreted this as a sign of disloyalty. On one such occasion, Mussharraf snapped back to Tariq that ‘If you are saying that so that the prime minister knows, let me tell you that I will tell him your views myself’. (6) This statement provides a clue to the state of mind at that time. Tariq was retired but given few days at his request until October 13 to say farewell to his formations.

Director General (DG) Analysis of ISI, Major General Shahid Aziz; a relative of Mussharraf was brought in as DGMO. Mussharraf had already brought his close junior confidant Brigadier Salahuddin Satti to head 111 Brigade in Rawalpindi. Satti had served as Brigade Major when Mussharraf commanded a Brigade. It is also alleged that some of Ziauddin’s subordinates (Major General Ghulam Ahmad and Brigadier Ijaz Shah) at ISI stayed with the ultimate fountain of power; COAS. Mussharraf made all these crucial changes to secure his own position fearing that Sharif was planning to sack him while Sharif interpreted these changes as potential move against him. Distrust and suspicion between Mussharraf and Sharif was mutual and many on both sides were whispering in the ears of their masters. Mussharraf was suspicious that one senior officer of his inner circle was informing the other side about decisions of military’s top brass while Sharif feared that his conversations at prime minister house were bugged by the military. Some also believe that General Head Quarters (GHQ) had a mole in Sharif’s inner circle, informing army brass about discussions in Sharif camp.

Once securing his base in the army, Mussharraf warned Nawaz Sharif through intermediaries. In his memoir, Mussharraf admits that ‘I had already conveyed an indirect warning to the prime minister through several intermediaries: “I am not Jahangir Karamat”.’ (7) In September 1999, Mussharraf met with Nawaz Sharif’s brother Shahbaz Sharif and bluntly told him to convey two things to his brother. First that ‘I would not agree to give up my present position of chief of the army staff and be kicked upstairs as Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee CJCSC’ and second recommendation of retirement of Quetta Corps Commander Lieutenant General Tariq Pervez. (8) By the first week of October, with the exception of DG ISI and a lame duck Quetta Corps Commander, all senior officers as well as some crucial mid level officers were Mussharraf’s trusted appointees.

GHQ embarked on a contingency plan in case Sharif made his move. CGS Lieutenant General Muhammad Aziz contacted Commander of Special Services Group (SSG) Brigadier Amir Faisal Alvi and a company of SSG was moved to Army Aviation base at Dhamial near Rawalpindi with cover of training with aviation. CGS also held a meeting with DGMO and Commander of SSG at his office and at SSG Commander’s residence. The discussion was about security of the president and prime minister house in case of breakdown of law and order. (9) General Mussharraf held a meeting at his residence prior to his departure to Sri Lanka. Participant list included CGS Aziz, Rawalpindi Corps Commander Lieutenant General Mahmud Ahmad, DGMO Shahid Aziz, Director General Military Intelligence (DGMI) Ehsan ul Haq and Director General Inter Services Public Relations (DGISPR) Brigadier Rashid Qureshi. In this meeting, it was disclosed that Sharif wanted to sack army chief and was trying to politicize the army. It was decided in this meeting that if Sharif tried to remove army chief, then army will take over. (10)

Sharif became aware of some of these maneuvers when a brigadier (he was a retired SSG officer who was working on contract basis) serving in Counter Intelligence (CI) section of ISI informed Sharif camp that something was in the offing. In the end of September, Ziauddin left for a trip to United States and returned on October 08. On the same day, when Ziauddin met Sharif, this issue was raised. Ziauddin asked head of CI Major General Jamshed Gulzar Kayani to investigate the matter. When brigadier was confronted, he claimed that he had never passed such information. (11)

Nawaz Sharif fearful of a pre-emptive strike from Mussharraf dispatched his brother Shahbaz to Washington on September 17. He pressed U.S. officials to issue a warning against the military coup. On September 20, US State Department issued a very strange warning stating that U.S. will not approve of any ‘unconstitutional moves’ against the government. (12) Ziauddin was also visiting Washington during this time. Former Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto was also in United States and she probably had picked up enough back ground noise to announce that Sharif government will not last until December.

On October 10, Sharif took a flight to Adu Dhabi and Ziauddin accompanied him. Probably, Sharif finalized his decision of sacking Mussharraf during this flight. It is not clear how much information he shared with Ziauddin. Mussharraf was on a visit to Sri Lanka. I’m of the view that probably at this stage, there was no plan of not allowing the Mussharraf’s plane to land in Pakistan. Both thought that while Mussharraf was on his way back home from Sri Lanka, the army will accept the change of command. Ziauddin was confident that he would be able to convince his colleagues and by the time Mussharraf has touched down in Karachi, he would have to accept the change. Ziauddin underestimated the strength of Mussharraf loyalists and was probably not aware of the fact that the decision reached among the close circle of Mussharraf that they will not allow Mussharraf’s removal.

In the evening of October 12, Ziauddin was appointed new army chief at prime minister’s residence. Ziauddin pointed to Sharif about the role of the president and Sharif rushed to the president house to get the signature of the president. Shrewd president Rafiq Ahmad Tarar only wrote ‘seen’ rather than approved on the file and signed it. The file was then handed over to Defence Secretary Lieutenant General ® Iftikhar Ali Khan to take to the ministry of defense and issue the official notification.

Ziauddin was well aware that two lieutenant generals who were holding two key positions (X Corps Commander Mahmud Ahmad and CGS Muhammad Aziz Khan) were staunch Mussharraf loyalists and will not accept the change. In addition, by virtue of their posts, they were in a position to thwart the plan. They needed to be removed from their posts as soon as possible. He appointed QMG Lieutenant General Muhammad Akram as CGS while MGO Lieutenant General Salim Haider was given back the command of X Corps at Rawalpindi. Akram arrived at prime minister house but Salim was playing golf and by the time he arrived, tables have been turned and he was not allowed to enter the prime minister house. Ziauddin informed Military Secretary (MS) Major General Masood Pervez about these changes. He then contacted other Corps Commanders to get them on his side. Ziauddin claims that he personally spoke to Karachi Corps Commander Muzzaffar Usmani, Mangla Corps Commander Tauqir Zia, Multan Corps Commander Muhammad Yusuf and Gujranwala Corps Commander Agha Jahangir Khan. When he tried to contact Peshawar Corps commander Saeed ul Zafar, he was told that Zafar was sleeping. (13) Ziauddin also called two of his subordinates at ISI Major General Ghulam Ahmad and Jamshed Gulzar Kayani asking them to come to prime minister house but they didn’t show up. (14) It was not surprising that knowing the awkward and very difficult situation most Corps Commanders remained un-committed. They were contacted by Ziauddin as well as Aziz and Mahmud at about the same time. Most of them waited on the sideline to let the winner emerge from this tussle. Aziz and Mahmud also had personal stakes in the whole affair. If any heads were going to role for the responsibility of Kargil operation after the retirement of General Mussharraf, it would be the heads of these two officers as they were the architects of the Kargil operation.

At 5:00 pm, Pakistan Television broadcast the news of removal of Mussharraf and appointment of Ziauddin as new army chief. Corps Commander of Peshawar Lieutenant General Saeed ul Zafar called Aziz who was playing tennis with Mahmud and told them about the change. Mahmud and Aziz rushed to GHQ and set in motion their plan to stop the removal of Mussharraf. DGMO Shahid Aziz rushed back to his office and his office became the temporary headquarter of the counter coup. Mahmud, Aziz and Shahid started to contact Corps Commanders. Most of the Corps Commanders now clearly seeing the stronger party decided to go with the hawks.

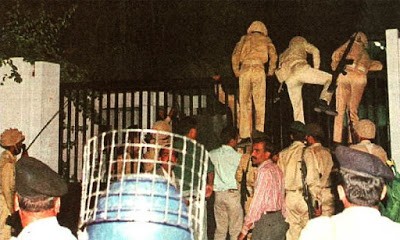

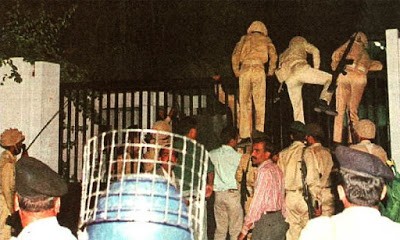

Soldiers from the two battalions of 111 Brigade were responsible for guarding president and prime minister house. 4 Punjab Regiment commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Javed Sultan was guarding president house while 3 Azad Kashmir (AK) Regiment commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Shahid Ali was guarding prime minister house. Mahmud contacted Brigadier Satti and ordered him to secure president and prime minister house. Aziz and Mahmud were well aware that the first thing they had to do was to stop the television broadcast. First team of fifteen soldiers headed by Major Nisar of 4 Punjab was dispatched to television station to block the repeated broadcast of Mussharraf’s removal. Major Nisar told the television staff to stop broadcasting the news. Two SSG detachments at Dhamial and Mangla were also rushed to Islamabad.

Sharif got alarmed when 6 pm news bulletin did not broadcast the news of Mussharraf’s removal. He sent his Military Secretary Brigadier Javed Iqbal Malik (a gunner officer of 4 Field Artillery Regiment) with an armed escort of elite police to television station to check what was going on. Probably, Sharif realized at this time that Ziauddin may need some time and Mussharraf should be kept out of country. Sharif ordered the airport staff at Karachi that airport should be closed and Mussharraf’s plane should be diverted to another destination. Brigadier Iqbal had a heated conversation with Major Nisar at television station control room and finally, Iqbal drew his handgun on Nisar, forcing him to order his men to disarm. The army soldiers were locked in a room and near the end of the bulletin, the news of Mussharraf’s removal was re-broadcasted. Now Mussharraf’s team watching the news at GHQ figured out that something went wrong. They sent another larger army team to television station which quickly took control and pulled the plug on television broadcasts. (15)

The small guard units commanded by Majors had already secured the president and prime minister house while awaiting other army teams to arrive. Lieutenant Colonel Shahid Ali arrived with a larger contingent and confronted fellow officers in the porch of prime minister house. Ziauddin, Akram and Javed Iqbal were in uniform along with an escort of two SSG commandoes and six plain clothes ISI guards of Ziauddin. Each side tried to threaten and bluff its way out of this situation. Finally, when two SSG commandoes laid down their weapons, the tide turned against Ziauddin and he finally ordered his guards to disarm. (16) After securing prime minister house, Lieutenant General Mahmud accompanied by Vice Chief of General Staff (VCGS) Major General Ali Muhammad Jan Orakzai came to prime minister house to confront Sharif. (17) Later, when Sharif was confined in an army mess, Mahmud, Aziz and Orakzai asked Sharif to sign on the paper declaring dissolution of national assemblies but Sharif refused. (18)

General Mussharraf accompanied by his wife Sahba, military secretary Brigadier Nadim Taj and ADC Major Syed Tanvir Ali (he was from Mussharraf’s old 44 SP Regiment and serving his ADC since Mussharraf was a Major General) was on a commercial Pakistan International Airlines (PIA) flight 805 and plane was approaching Karachi. Lieutenant General Muzaffar Usmani, commanding V Corps in Karachi asked General Officer Commanding (GOC) of V Corps Reserve Major General Iftikhar Malik to activate Immediate Reaction Group and take control of the airport to ensure landing of Mussharraf’s plane. The situation at the control tower of Karachi airport was now chaotic and staff was being given confusing orders. The senior civil staff was telling them not to allow landing of Mussharraf’s plane while military officials giving contrary orders. Iftikhar came himself on the line and told the staff to allow the plane to land. Brigadier Abdul Jabbar Bhatti was sent to the airport and by the time plane was heading to Nawabshah, Brigadier Jabbar took control of the airport and told the control tower staff to call the plane back to Karachi. Iftikhar also asked Brigadier Tariq Fateh; a serving gunner officer seconded to Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) as director at Karachi airport and in charge of airport security Brigadier Naveed Nasr to help the army contingent. Iftikhar also arrived at the control tower and spoke to Mussharraf but Mussharraf was not sure about the whole situation on the ground. Finally, Mussharraf’s plane safely landed at Karachi airport. (19)

In Lahore, Corps Commander Lieutenant General Khalid Maqbool was out of town. GOC of 10 Division Major General Tariq Majid was in charge and he sent troops to arrest Governor and secure Sharif’s home in Lahore and his large estate in Raiwand. Director of Punjab elite Police Training Center, Colonel ® Tariq Ehtasham (a former SSG officer) sent some elite police force to Raiwand estate but they were no match for the army.

Secretary Defence Iftikhar was on his way to Ministry of Defence when he received a call from Shahbaz asking him what army soldiers were doing at prime minister house. (20) His subordinate Additional Secretary of Defence Major General Shahzada Alam also informed him about the troop movement. Iftikhar knowing that the tide was turning decided to wait and didn’t issue any notification. Someone at the Military Operations (MO) Directorate from where the counter coup was being directed knew the importance of this technical detail and a Major from Military Intelligence was sent to bring Iftikhar to MO directorate. (21) In fact, later the legal argument used by Mussharraf was that as Secretary Defence had not issued the official notification, therefore his retirement order was not valid in strict legal sense and Supreme Court accepted this argument.

After the completion of the drama, winners got their rewards and losers paid for their sins. Mussharraf became President and ruled until 2008 when he was forced to resign. Key architect of the coup, Mahmud was appointed DGISI but later eased out after September 2011 seismic shifts while other key player Aziz served as Corps commander and later given fourth star and appointed CJCSC. DGMI Ehsan ul Haq was later promoted and served as Corps commander, DG ISI and finally CJCSC. Tariq Majid responsible for clearing the deck in Lahore was promoted and served as CGS, Corps Commander and finally CJCSC. SSG commander Amir Faisal Alvi was promoted to Major General rank but later sacked by Mussharraf. He was assassinated in Islamabad in November 2008. DGMO Shahid Aziz received third star and appointed CGS and Corps commander and after retirement served as head of National Accountability Bureau (NAB). 111 Brigade Commander Satti was promoted and served as CGS and Corps commander. Commanding Officer (CO) of the battalion securing president house Javed Sultan reached Major General rank. He died in a helicopter crash in February 2008. CO of the battalion securing prime minister house Shahid Ali retired at Brigadier rank. Brigadier Abdul Jabbar Bhatti responsible for securing Karachi airport was promoted Major General and served as COS of General Mussharraf and later Director of Regional Accountability Bureau in Punjab. Mussharraf’s military secretary Nadim Taj climbed up the promotion ladder and served as DGISI and Corps Commander. Tanvir Ali left the army in 2004 and committed suicide in June 2011. Ziauddin’s subordinate at ISI Major General Ghulam Ahmad was given third star and served as COS of Mussharraf. He died in a car accident in September 2001. Another subordinate of Ziauddin and head of Counter Intelligence wing of ISI, Major General Jamshed Gulzar Kayani was given third star and served as Corps Commander. After retirement, he was appointed Chairman of Powerful Federal Public Service Commission. He later developed some differences with Mussharraf and was removed from his post. Ziauddin and Javed Iqbal were arrested and punished through military procedures. Colonel ® Tariq Ehtesham was arrested and remained in NAB custody on corruption charges for two years but no charges were proven against him.

Events of October 12, 1999 were the unfortunate result of the clash between executive and his army chief. The two could not resolve their differences and their personal fears, suspicions and dislikes were aggravated by some of their close confidants. Kargil adventure was the final nail, pushing Sharif and Mussharraf into a dead end street. In the end, both acted according to their fears ignoring consequences of their actions for their own respective institutions as well as the country.

Acknowledgement: Author thanks many for their valuable input and corrections. Conclusions as well as all errors and omissions are author’s sole responsibility.

Notes:

1- Air Commodore Kaiser Tufail. Kargil and Pakistan Air Force, Defence Journal, May 2009

2- Author’s interview with a brigadier who was then serving with MI and involved in monitoring the mood in cantonments.

3- Owen-Bennett Jones. Pakistan: Eye of the Storm (New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 2002), p. 39

4- For details of Nawaz Sharif’s planning before sacking Mussharraf, see Jones. Pakistan, p. 40-48

5- Pervez Mussharraf. In The Line Of Fire: A Memoir (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2006), p. 111-12

6- Shuja Nawaz. Crossed Swords: Pakistan; Its Army, and the Wars Within (Karachi: Oxford University Press, 2008), p. 525

7- Mussharraf. In The Line of Fire, p. 110

8- Mussharraf. In the Line of Fire, p. 111-12

9- Carey Schofield. Inside the Pakistan Army (New Delhi: Pentagon Press, 2011), p. 119

10- Interview of Lieutenant General ® Shahid Aziz in Urdu, 13 May 2010, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x6kpHJTh9hU

11- Interview of Lieutenant General ® Khawaja Ziauddin in Urdu, October 31, 2010, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R6c72JVCl60&feature=relmfu

12- Nawaz. Crossed Swords, p. 524

13- Lieutenant General ® Khawaja Ziauddin interview, in Urdu, October 31, 2010, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s17v_LQqvZk

14- Interview of Saeed Mehdi; Principle Secretary of Nawaz Sharif who was present on the occasion, in Urdu, November 07, 2010, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QCvCJvzfiBs&feature=related

15- Mussharraf. In the Line of Fire, 124-125

16- Mussharraf. In the Line of Fire, 129-130

17- For details of events in Rawalpindi, Nawaz. Crossed Swords, p526-527, Mussharraf. In the Line of Fire, p. 120-123 and Jones. Pakistan, p. 44-45

18- Interview of Saeed Mehdi; Principle Secretary of Nawaz Sharif who was present on the occasion, in Urdu, November 07, 2010, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QCvCJvzfiBs&feature=related

19- Mussharraf. In the Line of Fire, p.126

20- Mussharraf. In the Line of Fire, p. 119 & 127

21- Mussharraf. In the Line of Fire, p.127

Hamid Hussain

October 02, 2012

coeusconsultant@optonline.net