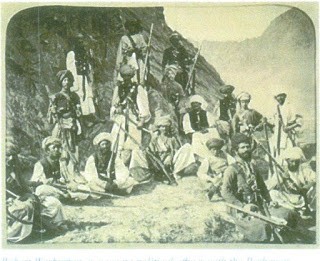

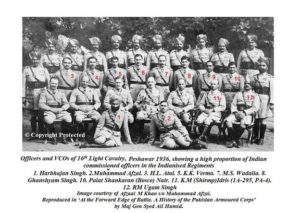

Corrected Officer List: Sitting on ground Left to Right: Lieutenant Harbhajan Singh (1) and Lieutenant Muhammad Afzal (2).

First Row Seated: Left to Right: Captain Khalid Jan, Captain Hira Lal Atal, Second-in-Command (2IC) Major Basil Holmes, DSO, Commanding Officer Lieutenant Colonel A. H. Williams, MC (with dog in his lap), Major Faiz Muhammad Khan, Captain K. M. Idris (11), Risaldar Major Ugam Singh (12).

First Row Standing: Left to Right: Unidentified VCO, Lieutenant Inder Sen Chopra (3), Lieutenant Enait Habibullah (4), Lieutenant K. K. Verma (5), Captain S. D. Verma (6), Captain M. S. Wadalia (7), Lieutenant Ghanshyam Singh (8), Lieutenant J. K. Majumdar (9), Lieutenant P. S. Nair (10) and unidentified VCO.

16th Light Cavalry was one of the first cavalry regiment of the Indian army that was Indianized. 7th Light Cavalry was the second cavalry regiment that was Indianized and later 3rd Cavalry was also earmarked for Indianization. Disproportionately, large number of future senior cavalry officers of Indian and Pakistani armies belonged to these three Indianized cavalry regiments. They were the founding fathers of armored corps of Indian and Pakistan armies.

King Commissioned Indian Officers (KCIOs) were graduates of Sandhurst and Indian Commissioned Officers (ICOs) were trained at Indian Military Academy (IMA) at Dehra Dun. During the war, Indian officers were commissioned as Emergency Commissioned Officers (ECOs) after only six months of training. The picture is circa 1936, therefore most Indian officers are KCIOs and only two ICOs as first IMA batch known as ‘pioneers’ was commissioned in December 1934. Both are from the first IMA course.

Major Basil Holmes: In this 1936 picture, he was Second-in-Command (2IC) of the regiment. He was an Australian and served with Australian army during First World War. He was ADC to his father Major General William Holmes who was killed by a shell in France during a tour. He won Distinguished Service Order (DSO) in First World War. After the war, he transferred to Indian army and after a career of twenty one years in India, retired as Colonel and went back to Australia. Continue reading 16th Light Cavalry. A historic picture and an anecdote from Kashmir