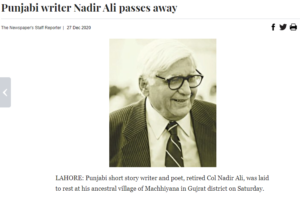

The following is from a talk given by Colonel Nadir Ali at BRAC university in Dhaka in 2007..

Bangladesh’s War of Liberation

Liberation War-Historicising a Personal Narrative

December 16, 2014 0 2,619 Views

|By Col Nadir Ali (Retd) , Pakistan Army|

Former Pakistani Col Nadir Ali’s talks of his experiences from 1971 in Bangladesh at the BRAC University in Dhaka.

Ladies and gentlemen,

Thank you for providing me with this opportunity to be in the great city of Dhaka and be in the BRAC University addressing this august gathering.

But this interaction can only be meaningful if you ask me questions. I will answer your questions honestly and candidly. Hopefully, we will add to each others’ knowledge in this interaction.

Historicizing a personal narrative is difficult in the best of times. Recalling 1971 is a very sensitive issue and it touches most of us very deeply.

First, a litte of the personal: I was in Dhaka at the Army Ordnance Depot at Tejgaon from 1962-1964 and in 3 Commando Battalion at Thakurgaon and Chittagong from 1965-1966. As an army officer, I also happened to know several Bengali officers who later became major players in Bangladesh . Among them, General Zia-ur-Rehman was a fellow instructor at Pakistan Military Academy. Brigadier General Khalid Musharraf was my roommate and course mate at Military Academy and a fellow officer in the commandos in the early sixties. General Mir Showkat Ali was also a course mate in the Military Academy . Major Ziauddin of the Naxalites and now a maulana is a personal friend. Brigadier Abu Tahir was a fellow officer in the commandos and a friend too. Many of my students at the Pakistan Military Academy also rose to high ranks in the Bangladesh Army. The life of an average West Pakistani officer in the then East Pakistan , remained confined to cantonments among the overwhelming majority of West Pakistani officers.

The handful of Bangladeshi officers who had also served in West Pakistan were naturally much more relaxed here. But the majority of Bengali officers remained distant from the West Pakistani officers, who occupied the command and key staff positions. I spent the happiest four years of my life here, but my life remained confined to family, office, officers mess, Dhaka Club. Language is the house of being. We remained non-beings in Bangladesh , or alien beings in this respect, because we did not learn the Bengali language and did not partake of the rich culture of this land.

While my personal experience in Bengal had been very positive, the story in the historical context was very different. The Bangladeshi fellow officers in the Pakistan Army rarely became close personal friends with West Pakistani officers. Even two of the very prominent Bengali officers, Lt Col. (Retd) Qayyum, whose elder brother was the Head of Bengali Dept at Dhaka University , and Group Capt MM Alam of air force who stayed on in Pakistan , are now alienated and lonely beings. People as prominent as Sher-e-Bangla Mr. Fazlul Haq and Mr. Husain Shaheed Suhrawardy, despite their prominence in the Pakistan Movement and Pakistan politics, were alienated by the dominance of West Pakistanis in politics, which resulted in the creation of the Awami League, which played a central role in liberation.

AK Fazal Ul Haque started his career as early as Praja Conference of 1914. Mr Surawardy was not only a Prime Minister, but opened the China door door and set up Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission and Pakistan Institute of Nuclear Technology. All these came to play key roles in our subsequent history. There may even be some lesson in history, in the sub-continental context, in the fact that the Neta Ji Subhash Chander Bose was the most fascinating of figure in the forties. He was very different from Mr. Gandhi. Who was more right is a question for you to decide. In any case, “History,”as Hegel said, “has a certain cunningness and history is always rational.”

We the Punjabi Pakistanis were fighting against reason and we were the oppressors. At the same time, Sheikh Mujib-ur-Rehman’s leadership defined the rationality of history. The Indian Army only acted on the rationale that had been created by the Awami League victory in the 1970 elections. But today I want to talk about Bangladesh and my limited personal experience in the midst of these historic and tragic events.

Before I move on to the grim events of 1971, let me recount some of my earlier experiences in Bangladesh that may illustrate the way we, as army officers, thought and were encouraged to think. One of the major political events of the sixties was the 1964 winter presidential election, contested by General Ayub Khan and Miss Fatima Jinnah. Historically, it was a non-event, but it gave me some insight into the working of the civil government at the time. I, a young non-entity of a captain, while doing election duty in Manik Ganj subdivision of Dhaka district, was personally called on the telephone by Mr. Monem Khan, the then Governor, to say that the area magistrate police officer and Member National Assembly were working for the Combined Opposition Party.

I submitted that I had come on duty in aid of civil power and the magistrate and police officer were supposed to tell me what needed to be done and not the other way around.

Again, while on duty during the Hindu-Muslim riots in Narayangunj area, I received a call from Governor House to ask why I was feeling restrained by the DIG Police and magistrate, i.e.: I should go out and open fire whenever I felt the need. During the day, I had been reprimanded by Gen. Yahya, the General Officer Commanding, as to why some civilians were standing around as he drove past. I said that I had been evacuating some Hindu families who had been attacked. “You are not the Red Cross, boy!” the General had roared. It is likely that he had reprimanded the Governor as well. I was then ordered to carry a machine gun instead of single shot rifles and the DIG and magistrate were removed. Legally, the position was that the GOC was junior to the governor and I was way junior to the DIG and magistrate, and I was also supposed to get their written permission before opening fire. But in actual practice, the GOC could order the governor around and I could freely bypass the civilian magistrate and the senior police officer.

The next significant political event in the sixties was the Agartala Case. In 1968, at Staff College , we were given a briefing by Director General Military Intelligence. It was done very dramatically, by shutting all doors and with music from the movie “From Russia , With Love.” It was a common joke in the officer messes, that the Bengali officers called each other “General”, a rank they would supposedly hold when they seceded from the Pakistan army.

What we had always treated as a joke was now being cited as “treason discovered.”! The farcical nature of the “conspiracy” can be gauged from the fact that someone as junior and insignificant as an air force sergeant and corporal were also mentioned as major characters in the conspiracy to topple state authority.

I felt then that we were headed for disaster because the powers that be were living in another world. The die was finally cast in the 1970 elections, but rumbles could already be heard. I was at heart against martial law and West Pakistan ruling over East Pakistan . But I was a young nobody and among a tiny minority in the army. The 1970 election was as cyclonic as the cyclone over Hatya Island that year. The Six Points had been voted for and that meant autonomy for then East Pakistan .

Bangabandu had thrice used the word ” Bangladesh ” in his election speech in Nov 1970. The then head of Pakistan Television, Mr. Roedad Khan, has written that he had told Sheikh Mujib-ur-Rehman to delete these words. But the agreement was to allow the leaders to say what they wanted and he refused to delete those words, it was aired as such. The results were stunning. History had been made. But while the fellow Bangladeshi officers were elated, West Pakistanis were not happy with the results.

Then came the unwillingness to accept the election results, the military action in East Pakistan and the Liberation War! The war touched your lives deeply and those who lived through it in Bangladesh mentally and physically paid a very heavy price. The entire population of Bangladesh was terribly oppressed when the army ran riot. Death stalked everyone’s life and neither life nor honor nor property was safe. I unfortunately, was a witness and participant in those events, though I never killed anyone or ordered anyone to be killed. Still, I knew and heard about a lot of killing and other atrocities. I may have a thousand stories to tell of what I saw from early April 1971 to early October. But one person’s, experience is not history nor its accurate picture.

I rejoined 3 Commando Battalion on 10th April, 1971 as second in command of the battalion and took over its command on 6th June 1971 and was there till the beginning of October 1971. A detachment of this battalion had arrested Bangabandu Sheikh Mujib-ur-Rehman on the night of 25th-26th March 1971, only two weeks before I joined it. I was directly under the Eastern Command Headquarter and I interacted frequently with General Niazi GO C-in C Eastern Command, and General Rahim and General Qazi, commanders of 14 Din and Gen Mitha who assisted Gen Tikka till Gen Niazi took over.

The first major incident was the arrest of Sheikh Mujib-ur-Rehman. Colonel Zaheer Alam, who led the detachment charged with arresting him, saluted Bangabandhu and said, “Sir, we have been ordered to take you into custody.”

According to his book, when he reported to Eastern Command after the arrest the three generals, Gen Hamid, Chief of Army Staff, Gen Tikka and Gen Mitha who were present all asked only one question: “Why did you not kill him?”

Imagine, if he had been shot, that would have been a catastrophe and changed many things even further for the worse. The reaction would have been far worse and the whole of Bangladesh would have gone up in flames.

But though we did not kill him then, did we not murder him as well as Mr Bhutto in a span of four years in the late seventies?

In Pakistan the state apparatus was dictatorial and willful and it got worse over time. The State’s insensitivity to the dictates of law and justice was neither political nor civilized. It would decide the fate and state of the nation. Murder Incorporated had taken over. I arrived in Bangladesh on 10th April 1971. On 11th April, 1971, I traveled to Rangpur as one of our sub units was there. The night before, I had heard enough accounts at Army and Air force messes. I wanted to orient myself.

Most of the boasting in the messes was of the night of the generals on 25th/26th March and how a brigade column from Joydeblpur had “sorted out” Dhaka . There were tales galore of the Mukti Bahini’s alleged massacre of non-Bengalis and there was an album of blood and gore at Chittagong .

When I got to Rangpur, the senior tank unit commander boasted of how he had lined up the miscreants, the noisy political workers who had taken over the town till 25th March. He added some professors too for good measure. Then he took them all to a nearby brick kiln and had them shot. When I asked if there was any resistance or use of arms by those people or others in town, he said,

“Nadir, you should have seen how they behaved before 25th March. They jeered at us”

….that jeering and protesting was apparently enough to earn them a summary death sentence.

Then he added,

“One of my Bengali officers too-he was protesting too much. I had him shot too.”

I mildly protested. “He was a fellow officer and only a proud kind?”. And he was a brother officer. Sympathy for civilians was even less likely. While the commanders in Rangpur were painting a picture of too much resistance in Rangpur, Gen Mitha had landed there in a helicopter single handedly with a Bengali ADC, whose pistol was the only weapon they carried.

He rebuked the local commanders. He had known Bangladesh and knew what and how much resistance was likely. Perhaps his background also mattered. Gen Mitha, from Mumbai, was married to a Christian lady of Bengali origin, whose father was Dr Chatterji, the famous philosophy teacher.

The other had come to be defined in religious terms in India and Pakistan .

Your level of education and political beliefs could go only as far as the fellow soldiers and your army commanders allowed it. There was a feeling of revenge among the troops for the social siege and aggressive political stance of the Awami League. The soldiers thought that Awami Leaguers were not patriotic. But the senior commanders/Generals led the way and decided that this supposed rebellion had to be put down with the force of arms.

Somewhere the think tank had also decided that Hindus were the root cause of the problem. Orders were given to spread out and pacify by force of arms, by terrorising and by picking out and killing the Hindus. A license to kill, given to a soldiery with a besieged mentality, to whom the whole of Bengal appeared alien, made it a free for all, a horrifying dance of death.

I had gone from West Pakistan . I found relief in walking out and seeing for myself. I drove all the way from Rangpur to Dhaka by road with only a driver and our personal arms. I faced no resistance or threat. If you were sympathetic with the politics of the people and could gauge the extent of resistance, you saw thought and behaved differently.

My first so called operation was on 15th April, after a day of aerial reconnaissance, I took off with two columns of commandos and was heli dropped east of Faridpur town. I was told “It is a hard area. It is Mujib-ur-Rehman’s home district. Go and let them have it! And pick out especially the Hindus.”

The man giving orders was my old teacher and friend. I said

“Sir, I cannot kill anybody who is not armed or firing at me. Don’t expect me to do that. That is against the law sir, even if it is martial law.”

He said

“You have just come from West Pakistan , teaching your Bengali students and drinking with your Bengali friends, you don’t know what has been happening here.”

When finally I was dropped on the road to Pabna, east of Faridpur, we took position and fired to make a base for ourselves. We were up high on the road. On the low ground, I saw some civilians running towards us. I halted the firing.

“What do you want?”

I asked the man with a bucket.

“We have brought water for you to drink.”

I ordered a ceasefire.

We sat down, resting against the bridge wall and started making tea. I asked the civilians,

“I saw Awami League flags here yesterday, from the air.”

“Sir, we have taken those down. We have put up a Pakistan flag. You can see one from here.”

I did not know whether to laugh or cry. Then I saw a glimpse of collaboration.

The villagers were kicking and dragging a poor fellow.

“Sir, he is an Awami Leaguer and was demanding mon;ey from the villagers.”

I searched his pockets and found some thirty bucks. I returned these to the villagers.

“Should I shoot him?” asked a soldier.

“I will shoot anyone who so much as touches his weapon.” I said.

But the villagers too wanted to join us in eliminating this innocuous symbol of rebellion. They wanted to earn our approval. Soon the main army column that had come through the city of Faridpur came by they were setting fire to every village along the road.

“What is the score?”

asked a Rommel like colonel standing in a machine gun fitted jeep.

“Sir, there was no resistance so we killed no one.”

He gave a burst from his machine and some of the innocent onlookers standing around us fell dead. “That is the way my boy,” the Colonel told this poor Major.

The next episode was around 25th April, to clear Barisal , the last district town to come under army control. I knew the area and had gone as a guide with the battalion attacking Barisal . The advance party of thirty who had gone by naval gun boats the night before was missing. The colonel waited out the night on the outskirts and called an air strike before moving in the morning. As we moved forward, the city of Barisal had already been conquered by our missing advance party of thirty men! Only a sweeper, whom the colonel had killed in panic, was a casualty. But after that the battalion did do a lot of killing and looting, as I learnt later during a tour of the area. Meanwhile, “Three-pronged attack on Barisal repulsed,” said a banner headline in an Indian paper from Calcutta .

On 6th June, from a dug-in position a regular rebel battalion of East Bengal Regiment in Belonia with minefields, repulsed a brigade attack from the Pakistani army. The 53 Brigade from Commila failed with forty dead. I was called in to give commando support to a reinforced brigade attack. The night before the planned attack I jumped into the midst of the battalion at night.

We faced little resistance as we were in the middle of forward and rear positions. Where the brigade attack had failed, I succeeded. The whole salient next morning was found vacant.

Somehow, with this I became a hero.

My CO, who had refused the mission, was sacked and I became commando battalion commander. The General commanding 14 Div Gen Qazi, after that took me along on most visits and I traveled all over Bangladesh . We provided flying guards to PIA aircrafts flying in the area and I could issue air tickets. I was very mobile.

One day after my taking over as a commanding officer, they announced demonetization of big denomination notes. I was sitting having tea in my balcony. It was raining and I saw a lot of high denomination notes flowing down into the drain. Some soldiers of mine had obviously looted those notes. My command was going to be difficult. I would never know what would happen when I turned my head!

I was also reminded of an event in a distant past. In 1947 after the first monsoon rain on Aug 16,1947, I had seen looted material floating down a drain. How many holocausts was one to see in a life time!

To stay away from the kill and burn forays on the home ground, I started operations across the border with volunteers provided by Jamaat-e-Islaami. I met Prof Ghulam Azam and Ch Rehmat Elahi, who used to come to my office. I also frequently met Mr. Fazlul Qadir Chaudhry and Maulana Farid Ahmed.

I did not indulge in any killing nor ordered any, but I was aware of a lot of killing and looting done by the army all round Dhaka . At the same time, a false sense of normalcy prevailed in the limited circuit of my social life i.e, Dhaka Club, Officers Mess, Chinese food near DhanMandi.

Meanwhile every Bangladeshi was oppressed and terrorized, even if not directly a victim of it. When I saw hundreds of abandoned cars on the Ghat on the road west of Dhaka and saw a fleet of cars in my own unit, I was aware of the missing or robbed masters. There were nearly 10 million refugees in India and more than ninety percent of them were Hindus. Thousands were killed and millions rendered homeless. Over nine million went as refugees to India. An order was given to kill the Hindus. I received the same order many times and was reminded of it . The West Pakistani soldiery considered that Kosher. The Hamood Ur Rehman Commission Report mentions this order. Of the ninety-three lakh (9.3 million) refugees in India, ninety lakh were Hindus Casualty figures may have been exaggerated, but every citizen was scared and oppressed and feared for his life. Nobody felt secure even in his own house.

What drove me mad? Well I felt the collective guilt of the Army action which at worst should have stopped by late April 1971. Moreover, when I returned to West Pakistan, here nobody was pushed about what had happened or was happening in East Pakistan. Thousands of innocent fellow citizens had been killed, women were raped and millions were ejected from their homes in East Pakistan but West Pakistan was calm. It went on and on .The world outside did not know very much either. This owes to the fact that reporters were not there. General Tikka was branded as “Butcher Of Bengal”. He hardly commanded for two weeks. Even during those two weeks, the real command was in the hands of General Mitha, his second-in-command. General Mitha literally knew every inch of Bengal. He personally took charge of every operation till General Niazi reached at the helm. At this juncture, General Mitha returned to GHQ. General Tikka, as governor, was a good administrator and made sure that all services ran. Trains, ferries, postal services, telephone lines were functioning and offices were open. There was no shortage of food, anywhere by May 1971. All in all, a better administrative situation than Pakistan of today ! But like Pakistan of today, nobody gave a damn about what happens to the poor and the minorities. My worry today is whether my granddaughter goes to Wisconsin University or Harvard. That nobody gets any education in my very large village or in the Urdu-medium schools of Lahore, where I have lived as for forty years so called concerned citizen, does not worry me or anyone else.

In Dhaka, where I served most of the time, there was a ghostly feeling until about mid April 1971. But gradually life returned to normal in the little circuit I moved: Cantonment, Dacca Club, Hotel Intercontinental, the Chinese restaurant near New Market. Like most human beings, I was not looking beyond my nose. I moved around a lot in the city. My brother-in-law, Riaz Ahmed Sipra was serving as SSP Dhaka. We met almost daily. But the site of rendezvous were officers’ mess, some club or a friend’s house in Dhan Mandi. Even if I could move everywhere, I did not peep into the hearts of the Bengalis. They were silent but felt oppressed and aware of the fact that the men in uniforms were masters of their lives and properties.

Dr Yasmin Sakia, an Indian scholar teaching in America, told me once an anecdote. When she asked why in the 1990s she could not find any cooperation in tracing rape-victims of 1971, she was told by a victim,” Those who offered us to the Army are rulers now.”

One can tell and twist the tale. The untold part also matters in history. Two Bengali soldiers whom I released from custody, were issued weapons and put back in uniform. They became POWs along 90 thousand Pakistani soldiers and spent three years in Indian jails. I discovered one of them serving as a cook in 1976 in Lahore. I had regained my memory. “Kamal –ud-Din you?” I exclaimed on sighting him. “Sir you got me into this!”

The Pakistani Army had thrown them out. The other guy teaches in Dhaka now.

The untold part of the story is that one day I enquired about one soldier from Cammandos unit. He used to be my favourite in 1962. “Sir, Aziz-ul –Haq was killed”, the Subedar told me rather sheepishly.

“How?” was not a relevant question in those days. Still I did ask.

“Sir! first they were put in a cell, later shot in the cell”.

My worst nightmare even forty years later is the sight of fellow soldiers being shot in a cell. “How many ?” was my next question. “There were six sir, but two survived. They pretended to be dead but were alive,” came the reply.

“Where are they ?”

“In Commilla sir, under custody”.

I flew from Dacca to Commilla. I saw two barely recognizable wraiths. Only if you know what that means to a fellow soldier! It is worse than suffering or causing a thousand deaths. I got them out, ordered their uniforms and weapons. “Go, take your salary and weapons and come back after ten days.” They came back and fought alongside, were prisoners and then were with difficulty, repatriated in 1976. Such stories differ, depending on who reports.

All these incidents, often gone unreported, are not meant to boast about my innocence. I was guilty of having volunteered to go to East Pakistan. My brother-in-law Justice Sajjad Sipra was the only one who criticized my choice of posting. “You surely have no shame,” he said to my disconcert. My army friends celebrated my march from Kakul to Lahore. We drank and sang! None of us were in two minds. We were single-mindedly murderous! In the Air Force Mess at Dacca, over Scotch, a friend who later rose to a high rank said, “ I saw a gathering of Mukti Bahini in thousands. I made a few runs and let them have it. A few hundred bastards must have been killed” My heart sank. “Dear! it is the weekly Haath (Market) day and villagers gather there,” I informed him in horror. “ Surely they were all Bingo Bastards!,” he added. There were friends who boasted about their score. I had gone on a visit to Commilla. I met my old friend, then Lt. Col. Mirza Aslam Beg and my teacher, Gen. Shaukat Raza. Both expressed their distaste for what was happening. Tony, a journalist working with state-owned news agency APP, escaped to London. He wrote about these atrocities that officers had committed and boasted about. It was all published by the ‘Times of London’. The reading made me feel guilty as if I had been caught doing it myself! In the Army, you wear no separate uniform. We all share the guilt. We may not have killed. But we connived and were part of the same force. History does not forgive!

When I received orders to move back to West Pakistan for my promotion at the end of September, I was suddenly shaken out of my state of unreality. I completely lost my mind. I got out of my VIP power boat over Rangamati lake and got onto a nauka to share dal bhat with the surprised poor boatman.

I was dined out later that evening by the rich and famous of Dhaka . I was also given a farewell dinner at Gen Niazi’s house, who as usual gave me the gift of some dirty jokes that always interspersed his daily order sessions.

I returned to West Pakistan and broke down with paranoid schizophrenia, completely out of touch with reality. I was a mental patient for two years, was hospitalized for six months and lost my memory in the process of treatment. I was retired as a disabled person in 1973.

Over many years, I have rediscovered and reconstructed myself as a Punjabi poet. I acquired a literary and artistic consciousness from Bangladesh and I hope I can now validly represent the literary conscience of Punjab .

Now, as a Punjabi poet and writer I offer apologies and ask forgiveness from those who suffered so terribly in 1971. And I want to say that there are many more in Punjab who feel the same shame and regret and who are also discovering a connection between the military mindset that led to those tragic events and our own loss of culture. But alas at the time of my departure no one except my brother –in- law Justice Sajjad Sipra, decried my choice of posting.

Today, the world is changing fast. Any of the three looming crisis: the falling dollar, rising oil prices or runaway inflation and high food prices may ruin us and the regional economy. Let Bangladesh , which is thriving after liberation, lead the way. And why not ; it was here that you first talked of praja, the people , swaraj the independence and Liberation War Mukti Judh. Be it Azad Hind Fauj. Krishak Praja Dal or Mukti Bahini, these all had their origin in Bangladesh .

Neither across the ocean nor across the Himalayas is anyone coming to rescue us. Together, we three can make a formidable alliance. Let us attend to our teeming millions of poor and not be misled by our habitually misleading leaders. Half of the entire world’s poor live in the sub continent. Let us not raise huge armies that can only destroy each other. I will sum up with Faiz Ahmed Faiz’s lines on Bangladesh :

“After how many Shraban rains,

Shall be washed the blood stains

After friendly intimacy.

We became strangers again.”

There was a lengthy question and answer session. Instead of twenty minutes I spoke for over an hour at the directions of the chair and people received it very well and wanted some more. There had been a lot of discussion on the subject of War Crimes Tribunal. When asked my opinion, I submitted, “Sir between you and me, the War criminals do very well in life. The real culprits always live well above the Law and only the poor and politically marginlised people will be prosecuted.”

Brown Pundit emeritus Zach pointed out on Twitter that BP launched at the end of 2010. A lot has changed. At BP and the world.

Brown Pundit emeritus Zach pointed out on Twitter that BP launched at the end of 2010. A lot has changed. At BP and the world.