Nonsensical Nemo’s Note: I am very grateful to the folks at Brown Pundits for allowing me to publish this. I have followed this blog for many, many years and learnt a lot reading it. If you guys enjoy my writing, you can subscribe to my Substack. Just one note, the piece was written before the 2024 Indian General Election Results came out on June 4.

That the Occident has been more or less wrong about India from the very beginning is evident from the fact that its most storied traveller, the so-called discoverer of the New World, Christopher Columbus, rolled up to the Bahamas and thought he had discovered India. It’s a tradition of blunders – sometimes perniciously mendacious and sometimes completely ignorant – that the Anglosphere (particularly its press) proudly continues to this day. Simply put, mendacity is the norm whenever there’s any report in any ‘esteemed’ Anglosphere publications about India. Most reports would fail to pass a basic smell – let alone a copy editor’s – test.

Suppose I was a foreigner and learned about India solely from American, British, Australian, or other Anglosphere news outlets’ coverage. In that case, I’d surmise that India is a genocidal hellhole where the living conditions were similar to, or worse than, sub-Saharan Africa, with a Wakanda-level technological might to run an Orwellian surveillance state, and whose streets are patrolled by saffron-hued Stormtroopers carrying tridents.

Every news report, opinion piece, editorial, and analysis appears to be a regurgitative exercise of the same set of phrases – “democracy backsliding”, “rising intolerance,” or “snarling hypermasculine Hindu beasts” – repeated ad nauseam.

While the WENA (Western Europe and Northern America) has always been suspicious of a rising India, the rabid foaming has only increased since 2014 when Narendra Modi, a man they detest for various reasons, came to power.

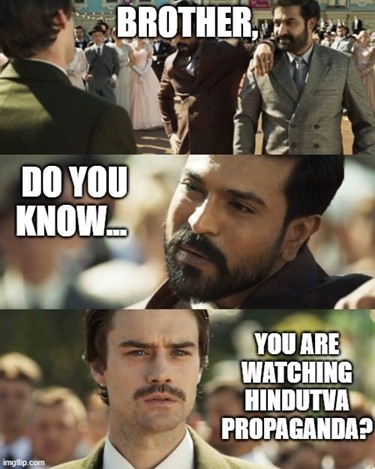

As a consequence, most of the reportage about India, including its diaspora, in recent years – from its elections to a citizenship law for vulnerable minorities in its neighbourhood to an Oscar-winning film like RRR – portends to “rising Hindutva fascism.”

RRR – a troubling tote of Hindutva propaganda

The latter is particularly hilarious, like this Slate piece that refers to a fantastical action sequence (the protagonist takes out Brit forces with his bow and arrows in a manner that wouldn’t be out of place in a Marvel movie), and claims that it’s an “apt representation for a country that employed authoritarian tactics to empower violent Hindu nationalism”.

Imagine this: You see a long-haired man shooting arrows at actors portraying Britishers with a bow borrowed from a Lord Rama statue and your instant thought is: “This is what it must be like for minorities in India.”

The aforementioned piece also takes great umbrage to the protagonist’s sartorial choice of saffron robes, which, in reality, was the choice of the attire of the original freedom fighter that the character was based on.

An interview with the director practically accused him of being a shill of the current dispensation without a shred of evidence.

One piece by Aatish Taseer titled Can Bollywood Survive Modi? in the Atlantic, claimed Rhea Chakraborty, had been arrested for abetting suicide, where the actual arrest was on drug-related charges.

For the uninitiated, Rhea Chakraborty is a Bollywood actor who was dating Sushant Singh Rajput, another actor, who committed suicide. His death became a cesspool of conspiracy theories that made the Indian mainstream media completely lose their marbles (at one point an Indian media anchor thought the text “Imma bounce” referred to a bounced cheque!).

The same piece in The Atlantic claimed that Karan Johar (one of Bollywood’s top directors) was targeted for showing gay themes in his movies, which is supercilious, and without any evidence to back it. In fact, close Bollywood watchers would tell you that Karan Johar’s movies have always been criticised for stereotyping the LGBTQI community, and in the KJo universe one’s position on the Kinsey Scale is determined by the angle of flaccidity in one’s wrist position. Johar, for his part, has even been spotted in selfies with Narendra Modi, and some could even argue that much of Johar’s filmography actually pushed the concept of the Hindu joint family long before BJP was a political force.

That’s not to argue that the current regime (Modi’s BJP) is any more LGBT-friendly when seen from the WENA lens. Still, it must be noted that while they did oppose same-sex marriage, the current regime didn’t oppose the decriminalisation of Sec 377, a law that was continually opposed by numerous “progressive” Congress-led governments.

Even the installation of a statue of one of India’s greatest freedom fighters, Subhash Chandra Bose was deemed by Financial Times’ Edward Luce, to be an “exhibit of Modi’s fascist ideology.” The closest one comes to this delinquency in the West is the way that America’s founding fathers are targeted for their past behaviour that might be considered deplorable now but was once the norm like keeping slaves. And without slave traders funding scholarships, our Rajya Sabha (India’s House of Lords/Senate to draw a crude analogy) would be far poorer intellectually and vocally.

Farm Bills: 250 million protesting in the streets?

A less laughable example is the coverage of the Indian government’s Farm Bills – a set of 3 laws that sought to democratise the marketplace for poorer farmers and end unlimited subsidies for rich ones.

Simply put, these laws aimed to change how agricultural produce is sold across the country by opening up sales outside of the state-run APMC mandis (marketplaces), remove barriers to inter-state trade, and also included a framework for electronic trading.

One of the laws, The Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Act, of 2020, prohibited the state governments from levying any additional fees on the farmers if they sold in an outside-trade area, and aimed at breaking the monopoly of the government-regulated mandis, allowing the farmers to sell directly to buyers. Another one had a framework, including a legal one, around contract farming to help small and marginal farmers transfer the risk of market predictability from the grower to the sponsor and realize better prices. The Essential Commodities Act was largely around the deregulation of ECA 1955, to not only help farmers with surplus harvests but also to encourage private and foreign direct investments in the sector to help build a robust supply chain infrastructure for the agricultural sector across the country, enabling both domestic and export markets. While these laws do need more work along the lines of price assurance and educating small and marginal farmers about the laws themselves, the coverage seemed to suggest that the government was forcing poor farmers to hand over their products to big, bad corporations.

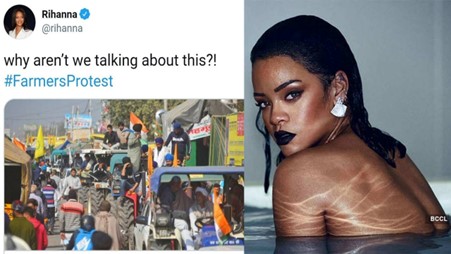

If you’d read the coverage – with in-depth insights and inputs from Rupi Kaur, Mia Khalifa, and Rihanna – you would’ve believed that the Modi government was trying to destroy agriculture in India and that the mob was modern-day freedom fighters taking on tyrants.

One of the more fictitious claims about the farm laws protests – that bordered on magic realism and where both math and logic took a hit – was that 250 million farmers were protesting all at once, a number cited by BBC and repeated by CNN. For the arithmetically inclined (or disinclined), that’s roughly 75% of the entire US population (but a mere 17% of the Indian population) allegedly hitting the streets in protest at the same time. It’s fair to say that if that many people hit the streets, everything would come to a grinding halt. What’s more interesting is that these preposterous claims still haven’t been corrected on websites of legacy media outlets that go around accusing every group that doesn’t belong to their particular political persuasion of being “fake news”.

The revolt was largely led by, as Anil Padmanabhan explained in an explainer in Mint, rich farmers/middlemen of Punjab and Haryana, two states with massive agricultural infrastructure that had become used to government doles (starting as far back as the Green Revolution era) who also hold a lot of political clout. The legislation on the other hand sought to empower the poorer farmers, to replace the current trading system controlled by a few which is out of reach for 75% cultivators in India.

For a detailed take on the Farm Bill, here’s a thread with the most cogent pieces on its pros and cons.

Abrogation of Article 370

The abrogation of Article 370 – a temporary provision that allowed extra-constitutional rights to the denizens of the state of Jammu and Kashmir – which was discriminatory against women, minorities, lower-caste folks, and the LGBT community – was also a classic example of a bad-faith argument. The abrogation of Article 370 also led to the abolishment of Article 35A, which defined “permanent residents” that discriminated against women and non-Kashmiris. For example, under Article 35A, women who married non-Kashmiris could no longer inherit property in Jammu and Kashmir. Similarly, any changes in Indian law, like the Goods and Services Tax (GST) or the decriminalising of homosexuality (striking down Article 377) would not be allowed in Jammu and Kashmir. Article 370 was always meant to be a temporary provision but became an albatross around New Delhi’s neck that defined its entire foreign policy for decades.

As a corollary, for non-Indian readers, imagine that there exists a state in the USA (let’s call it Texas) where women aren’t allowed to inherit property, US citizens who have settled there aren’t allowed to vote, and LGBT folks can be arrested for liking JK Rowling. Would removing said provisions be considered a step forward or backward?

Aadhaar – A State Surveillance Tool?

Amongst all these, the one that is probably most ludicrous is the coverage of Aadhaar. An identification document technology that has helped the Indian state reach its most vulnerable – which the World Bank believes could help India meet its poverty alleviation target – is coloured as a tool of mass surveillance.

The Aadhaar is similar to the Social Security Number (SSN) in the US, which was originally created to track accounts, and eventually morphed into an identifier. Do we deign to call SSN a mass surveillance tool?

One of the problems the Indian state has often faced is corruption, facilitated by the middleman. In the 1980s, former Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi noted that for every rupee the state spent, only 15 paise (15% of the amount) reached its intended beneficiary. On the other hand, with a combination of Direct Bank Transfer (DBT) and JAM, the Modi regime claims will help every rupee reach its intended target.

The JAM trinity refers to:

1) Jan Dhan (People’s Money) – bank accounts that provide access to financial services for people in the lower income strata for the first time

2) Aadhaar – a digital financial address

3) Mobile – Mobile phones armed with cheap data (thanks to Mukesh Ambani-owned Reliance Jio lowering the rates on mobile internet data packs)

Combined, the three have reshaped India’s financial landscape and broadened its access. The Economic Survey 2023 says that 318 central schemes are included under the Aadhaar Act 2016 that facilitate these transfers.

Aadhaar also played a critical role during COVID-19, when it became the backbone of COWIN (Covid Vaccine Intelligence Network), which helped India give 2.2 billion doses of vaccines and also helped create a digital certificate. As India’s outgoing Foreign Minister S Jaishankar shared in a delightful anecdote, when he went to have a meal in America, his son, an American citizen, took out a piece of paper to show his certificate while Jaishankar just showed his digital certificate on the COWIN platform.

CAA for Vulnerable Minorities

The Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), which sought to help out the most vulnerable minorities from neighboring states, was painted as a bill to disenfranchise and strip the citizenship of India’s Muslim population. For the uninitiated, the Citizenship Amendment Act’s raison d’etre was to give fast-track citizenships to Hindus, Sikhs, Jains, Christians, Parsis or Christians from India’s immediate neighbourhood: Bangladesh, Afghanistan, and Pakistan. It’s a matter of public record how non-Muslims are targeted in these countries and that their numbers have been dwindling significantly. However, the bill was gravely misrepresented in most of the Anglosphere outlets that claimed that the bill would be used to strip Muslims in India of their citizenship.

Similar to the Farm Laws, misinformation about the CAA ran riot, with mobs clashing with police across India that led to at least 69 deaths.

Claims were made that the CAA could be used to even deport illegal immigrants. The fact remains that irrespective of the CAA, any illegal immigrant would be deported under the Foreigners Act 1946 and Citizenship Act 1955.

As Harish Salve, one of the finest legal minds of this generation, who also happens to be the King’s Counsel in England and Wales, pointed out in a column: “I fail to understand how a law which is designed to confer the benefit of an identified class of persons, and which identification is based on a rational criterion, can be condemned as being discriminatory on the ground that the legislation could have created a wider class, arrived at by applying a broader criterion for identifying the class of those who would benefit from the legislation. The principle of equality does not mean that every law must have universal application. The principle of equality doesn’t take away from the state the power of making classifications.”

Salve also points out that there’s nothing “unconstitutional” about classification based on religion and that the Indian Constitution confers special rights upon members of religious minorities in India.

The Prophet Row

In May 2022, comments by Nupur Sharma, a former BJP spokesperson, about the Prophet Muhammad on a TV show were presented without context in media across the world. For the uninitiated, during a debate, a cleric was making incendiary remarks about a Hindu deity when an enraged Sharma quoted Hadiths that sparked worldwide condemnation.

The issue and the subsequent outrage were widely covered in the Anglosphere press. However, none of the pieces sought to mention that the comment was in response to an Islamic cleric mocking Hindu deities. Even the reportage afterward about several beheadings and large-scale riots by the Islamist fundamentalists laid the blame at the feet of the former BJP spokesperson, which is akin to blaming The Beatles for the Charles Manson murders. Much like Salman Rushdie, the spokesperson now lives in near isolation, in fear that she will one day be targeted by some Islamist fanatic for her remarks. Ironically, even Aatish Taseer, whose father was a former Punjab governor and lawyer, Salman Taseer, was shot dead in Pakistan for supporting a blasphemy accused in Pakistan, appeared to enjoy Nupur Sharma’s misery.

A BBC report on the beheading of Kanhaiya Lal – a Hindu tailor who had expressed support on social media for Nupur Sharma – by Muslim extremists had the lead image of angry protesters in saffron that would give the impression that the beheading was carried out by the Hindu fundamentalists. Time magazine even went as far as to publish an article titled ‘Hindu Lives Matter’ Emerges as Dangerous Slogan After Horrific Killing in India right after the murder of Kanhaiya Lal, burnishing the point that Hindu lives didn’t matter. In its own way, it was reminiscent of the gaslighting of Jews that seems to be now rampant in American universities, where the victim is blamed for, well, being the victim.

Also, the quantum of crimes, depending on the religion of the culprit and victim, is often gravely misrepresented in the media.

In fact, WENA outlets have been shoehorning the term “Hindu fascists” into every international conflict, including the Israel-Hamas war, where they claimed internet Hindus were accused of sowing disinformation. The Atlantic carried a piece whose entire edifice was based on the claims of a propagandist masquerading as a fact checker, who has been at the forefront of amplifying Hamas propaganda.

Saffronphobia?

Along with demonising Indians, there also seems to be a growing liberal consensus around Saffronphobia – which states that any news that involves a Hindu anywhere in the world has to be blamed on “rising Hindu Nationalism,” whether it’s a fake caste war in California, America or violence in Leicester, UK. The latter was blamed on “Hindu nationalism” with the heading (with an image of Lord Rama in the main picture) before grudgingly admitting that it “wasn’t one-sided” and that some Hindu religious symbols “might have been” desecrated.

Along with false reportage that put folks at risk, a Henry Jackson Society report stated: “False allegations of RSS terrorists and Hindutva extremists organisations active in the UK has put the wider Hindu community at risk from hate, vandalism, and assault.”

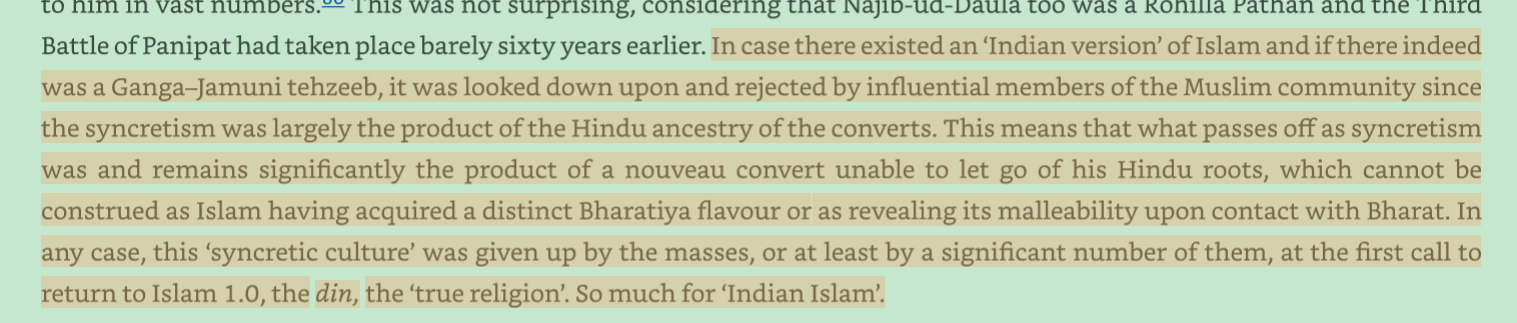

This is even more pernicious since those who are quick to blame Hinduism or its caste system for almost all of the world’s evils are the first ones who go to great pains to explain why Islamist fundamentalism has nothing to do with terrorism.

Tum Ghulam Log…

More recently, the focus has shifted to New Delhi’s foreign policy, which should’ve been expected, because if there’s one thing that irks imperialists who love the imaginary rules-based international order (RBIO), it’s countries that refuse to toe their line or accept the global liberal worldview as their own.

This results in the so-called powers-that-be getting extremely agitated about everything an administration does, even if it’s simply taking care of a law-and-order situation involving students or farmers. Meanwhile, the upholders of the so-called RBIO have no issue treating pro-Palestine protesters on Ivy League campuses like hardened criminals (I’m not sure I get this, it was quite the opposite) or socially and financially ostracising anyone who supports protesting truckers. GoFundMe even withheld millions of dollars donated to the truckers.

A lot of outrage in the last six months has been about India’s so-called death squads that make it sound like there are actual Indian operatives who are actually capable of spy-like skulduggery that would gladden George Smiley’s heart. One claim that would’ve really made Smiley smile involved a jihadi shooting down another jihadi in Pakistan with the promise that the agent would then help him join ISIS. A report notes: “Muhammad Abdullah allegedly told Pakistani investigators he was promised he would be sent to Afghanistan to fight for IS if he passed the test of killing an “infidel” in Pakistan, with Ahmed presented as the target. Abdullah shot and killed Ahmed during early morning prayers at a mosque in Rawalkot, but was later arrested by Pakistani authorities.”

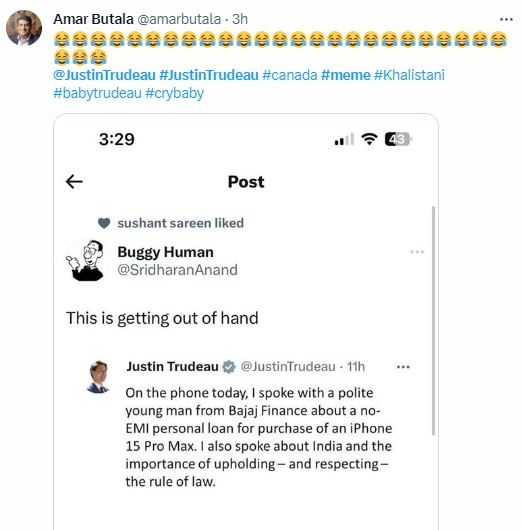

One such incident involved the killing of Hardeep Singh Nijjar in Canada. Coverage about Nijjar, who was described as everything from a plumber to a priest, did not mention the fact that he received training in Pakistan from that country’s notorious external intelligence agency ISI and that he literally ran a terror cell in Canada.

Justin Trudeau, in particular, went to town after Nijjar’s killing, blaming New Delhi, and his viral tweet about the rule of law became quite a popular meme.

Perhaps he was still smarting from the lack of cameras on him during the G20 Summit in Delhi, where he was also force-fed a millet-based diet. That Trudeau or his government was unable to provide any definitive evidence of the allegations doesn’t bother the outlets that have moved on to the next piece of misinformation.

Of course, in their alacrity to show New Delhi as the great big evil on par with Moscow, they forget to mind their Ps and Qs, like this error-ridden The Guardian article that announced Gurpatwant Singh Pannun’s departure for the Elysian Fields even though he continues to live and breathe and threaten Indians from America soil. It’s fair to say that if a Pannun was to do the same about America – perhaps threatening a RyanAir flight standing in New Delhi – he’d be neutralised faster than you can sing the chorus to Mundiya to bach ke rahi.

And finally, the reportage has entered its peak feeding frenzy to coincide with the Indian General Election 2024, in which critics of the current dispensation have to live with the harsh reality that this might be Narendra Modi’s third term, making him the only Prime Minister after Jawaharlal Nehru – whose pre-disposition to be an Englishman (his words not mine) – was far more palatable to the Anglosphere than the incumbent.

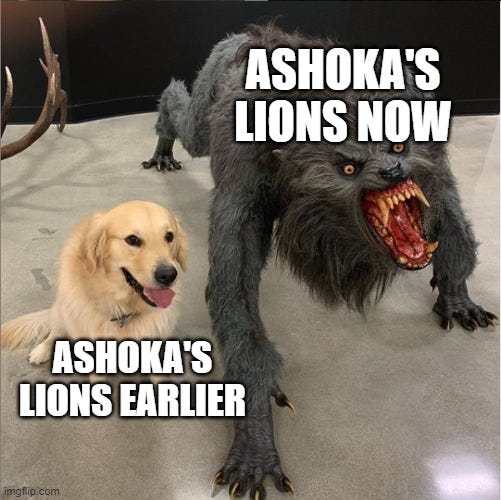

The election coverage has gotten increasingly more ludicrous with time. Among other things, Modi has been accused of building too many highways, attempting to create a messianic cult bigger than Gandhi, metamorphosing the Ashoka lions (India’s national emblem) that are referred to as “snarling hypermasculine Hindu beasts”, forcing the BBC to split its Indian operations to follow the newly-introduced foreign investment rules, and accused of election rigging without a shed of proof.

Meanwhile, the Opposition has been systematically lionised and beatified beyond their actual political standing or ability to elicit a response from the electorate.

The Obama Delusion Syndrome

It has become the norm for Anglosphere outlets to valorise individuals beyond their actual political clout, building them up much like Barack Obama, the patron saint of liberals across the globe (who conveniently forget his drone strike rate). They have done it with numerous Opposition figures including Congress’ de-facto leader Rahul Gandhi, Shiv Sena chief Uddhav Thackeray (whose father was a staunch BJP ally and hardcore Hindutva leader), West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee, former Lok Sabha MP Mahua Moitra, Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal and, where there are no politicians around, even Bollywood megastar Shah Rukh Khan. In fact, a large population actually argued that the success of Shah Rukh Khan’s film Jawan was a vindication of the Modi government’s targeting of Shah Rukh Khan’s son Aryan Khan in a drug-related case.

Nowhere is this Obama Delusion Syndrome epitomised than the coverage afforded to ex-TMC MP Mahua Moitra, whose profile fits that of the urban and sophisticated anglophile.

A New York Times piece written by Moitra read: ‘I Know What It Takes to Defeat Narendra Modi’, referring to the TMC’s (a regional party from the state of West Bengal) defeat of Narendra Modi’s BJP in the state elections in 2022. The piece obviously glossed over the excesses of violence that are part and parcel of the state of West Bengal, which was once ruled by the Communist Party of India (Marxists) that was renowned for its thuggery and has to its credit India’s biggest massacre of Dalits who came to India as refugees from Bangladesh. For the uninitiated, the term ‘Dalit’ refers to a socially and economically demographic at the very bottom of the social hierarchy.

Their vanquisher and subsequent successor is equally accused by critics of unleashing a reign of terror in the state against political opponents. In fact, in Bengal, to support BJP is to literally risk life and limb. This has often seen BJP legislators, like singer Babul Supriyo (whose car was attacked by goons), switch to TMC (on the other hand, several TMC legislators flipped to BJP ostensibly after pressure from various federal agencies like the Enforcement Directorate).

However, none of the pieces that valorise Moitra mention the serious charges against her (including sharing privileged Parliamentary access with a business rival of Gautam Adani. Instead, Mahua’s disqualification from parliament was labelled a misogynist witch hunt without even referring to the case that caused her to be disqualified.

More recently, when Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal was released after being arrested for repeatedly ignoring summons by authorities, FT claimed that Modi would face a “shake-up” after the release of a rival without knowing how to recognise the rival’s face. The picture in the frame is that of Sanjay Singh, a legislator of the Aam Aadmi Party, not Arvind Kejriwal.

Now this is not an exhaustive list and if I were to list every single mendacious claim masquerading as a fact in Anglosphere publications, this piece would become longer than Marcel Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu (In Search of Lost Time).

But it’s a fair example of the mendacity masquerading as facts in the English publications from the Anglosphere that they will go out of their way not to publish the perspective of the BJP or its ideologues, nor try and understand why a majority of Indians have voted for Narendra Modi in the last two general elections. There is no attempt to understand why Modi is so popular, or why his politics (Hindutva) cuts through caste. There’s barely any mention of the social welfare benefits that are at the heart of the development project with the slogan: Sabka Saath Sabka Vikas (Everyone Together, Everyone’s Development). In fact, foreign observers would be shocked to learn that Modi’s harshest critics on the right-wing side of the aisle often accuse him of being too soft on Islamists, labelling him Maulana Modi and would prefer a more hard-lined approach claiming that minorities got more benefits under Modi than previous governments.

There’s also no mention of how popular Modi – himself from a backward caste – is actually with so-called marginalised groups – either tribals or those from backward castes. There’s no mention that Modi’s regime has chosen Presidents – the Presidentship in India might be ceremonial but is highly symbolic –from a member of a backward caste as well as from a backward tribe as Presidents during its tenure. The latter was the first instance of a member of the backward tribe becoming a President.

The fact is that they don’t even want to know the BJP’s side of the story or why almost 230 million people (still fewer than BBC’s imaginary 250 million farmers protesting) voted for the party in the 2019 Lok Sabha Election. There’s no attempt to understand what it means for the millions who got their first bank account, gas stove, or toilet in the house. There’s no desire to comprehend why Hindus might clamour for a temple at Ayodhya, the abode of their most beloved deity, a temple destroyed by a Mughal ruler and replaced by a mosque.

That there’s a desire for constant obfuscation about India is evidenced by the experience of Swapan Dasgupta, a veteran journalist who went from being a Trotskite to a Thatcherite, who has also served as a member of the Upper House of Indian parliament. Dasgupta, who has long been associated with the BJP and its ideology, was commissioned by an editor of The New York Times to write an essay explaining the BJP’s perspective, but the idea was later killed for editorial reasons.

While the misrepresentation of what’s happening in India is not new and certainly not only for Modi and his government, but the misinformation has certainly magnified in recent times.

It would appear that the Anglosphere outlets would rather live in a state of cerebral inertia than try to understand how a party with two Parliamentary seats in 1984 has now won two national elections with overwhelming majorities and looks set to win the third.

A day ahead of the 2024 Election results, The Guardian summed up the mood best when it wrote that it was depressed in a statement that can only be read as deeply dismissive of Indian voters and their right to choose a candidate who might not appeal to the ivory tower philistines:

“In India, poor people often see politicians as gods delivering relief to numb the pain of reality. By claiming to be divine, Mr Modi is making devotees of voters, encouraging a belief that it is God’s purpose to target minorities, outlaw dissent, and ride roughshod over constitutional protections. It is depressing to think that Mr Modi will win a third election victory. There is small comfort in believing the BJP probably won’t achieve Mr Modi’s goal of winning nearly three-quarters of the country’s 543 parliamentary seats. Foreign investors are pulling out their cash from India’s stock market, citing uncertainty about the results.”

Evolutionary biologists believe that the “depression” gene is imperative for human survival, simply because it allows people to not seek out the company of others which helped them survive epidemics that ravaged tribes. So perhaps, a little depression isn’t the worst thing.

All of this brings us to the second part of the essay, which I hope to cover in Part 2, which will hopefully be published before I leave for the Elysian Fields:

Why is there so much misinformation about India in the Anglosphere?

Also Read:

1) Why I love RRR Part 1: An Absurdist Deconstruction

2) RRR Part 2: Why SS Rajamouli’s masterpiece triggers Hinduphobes

3) When are we going to talk about Hinduphobia?

5)Kashmir Checkmate: Amit Shah planned intricate political chess…

6) A revolt of the rich peasants of Punjab, Haryana

7) Why women vote for Modi

8) Where did the BJP get its votes from in 2019?

9) CAA is necessary: Why the many arguments about its being unconstitutional don’t hold water

10) Hindu-Muslim civil unrest in Leicester: “Hindutva” and the creation of a false narrative