There were many responses to my post on the Maratha Mindset: How to Control Your History and Emotions to Grasp the Future on Your Terms. I didn’t have the time to respond in detail, but a few conversations suggest I could be a bit more clear.

The primary issue that I’m alluding to is that a nation-state does not come out of thin air. They come out of history, historical memory, and organic cohesive identity. Victor Lieberman’s Strange Parallels argues that the mainland Southeast Asian nations developed nation-states rather easily (e.g., Vietnam, Thailand, etc.) because of a particular geopolitical background that they share with Western Europe. The contrast here might be with recently independent African nations, which often were literally constructed out of colonial-era compromises between European nation-states. Not so with Vietnam or Thailand, which had 1,000-year evolutions as political entities.

The primary issue that I’m alluding to is that a nation-state does not come out of thin air. They come out of history, historical memory, and organic cohesive identity. Victor Lieberman’s Strange Parallels argues that the mainland Southeast Asian nations developed nation-states rather easily (e.g., Vietnam, Thailand, etc.) because of a particular geopolitical background that they share with Western Europe. The contrast here might be with recently independent African nations, which often were literally constructed out of colonial-era compromises between European nation-states. Not so with Vietnam or Thailand, which had 1,000-year evolutions as political entities.

This moves me to the idea of India as a nation-state. It is clear that the Indian subcontinent has a broad civilizational affinity and unity. This was recognized by ancient Indians themselves, and it was recognized by outsiders. But civilization does not mean a nation-state. Western Europe is “the West,” the set of societies united by the Western Christian Church (later to become Protestants and Catholics). Aside from very short periods (e.g., the Napoleonic Empire) Western Europe, like mainland Southeast Asia, has been divided between different sub-civilizational units which developed a cultural and national coherency.

China is an exception to this. It has been a civilizational empire for 2,000 years, and today is the archetypical civilizational nation-state. It is, in some ways, what the Republic of India should aspire to become. The Chinese government has been pushing for Standard Mandarin to be known by the whole population within a few decades, without much controversy. The Han Chinese have long had a unitary political identity, no matter their internal linguistic diversity (which is dampened by the common written language).

Going back to India, it is clear that the construction of a nation-state and national institutions is a process. It is work. It does not naturally emerge out of thin air through fiat. In the previous post, I contrasted the Gangetic plain, in particular Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, with Maharashtra. What was I pointing to there?

The Gangetic plain has a strong civilizational identity. In this way, it is similar to many Arab Muslims, who have a strong identity as Arab Muslims. Arab Muslims also have weak national identities and strong local identities. This is a problem for nation-states because they need intermediate identities into which the local identities can flow. It’s a matter of organization that leads to structural cohesion.

The peoples of the Gangetic plain have strong communal identities, but weak regional identities. The communal identities were so robust that the vast majority did not convert to Islam. But with the weakening of the exogenous pressure, they need intermediate identities around which they can coalesce around to scale-out the social structure.

But how? One way you can do this is to focus on a national origin myth. But this presents a problem. The dominant indigenous polities of the Gangetic plain since 1200 A.D. have been Islamic and usually Turkic. Many Hindus on the Gangetic plain would argue that these were not even indigenous polities. Setting that aside, it does seem that the Mughals are ill-suited to being the binding historical precedent due to popular alienation (Ranjit Singh is too sectarian). There were obviously non-Muslim polities in the Gangetic plain before 1200 A.D., but myth-building at such a distance is not optimal. The Shah of Iran in the 20th-century attempted to reconfigure Iranian identity around that of the ancient Persians, but this was too tenuous a connection for most of the populace, which was more rooted in the Shia identity that came down from the Safavids.

In South India, even the Vijayanagara Empire may not be recent enough to serve as a concrete basis for myth-making.

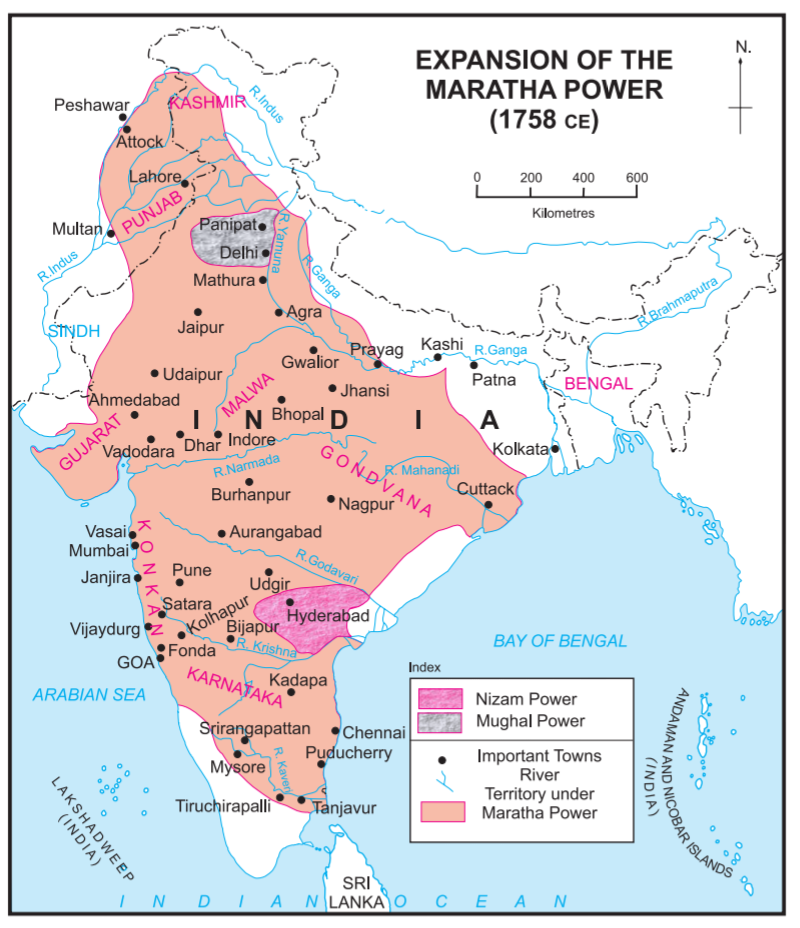

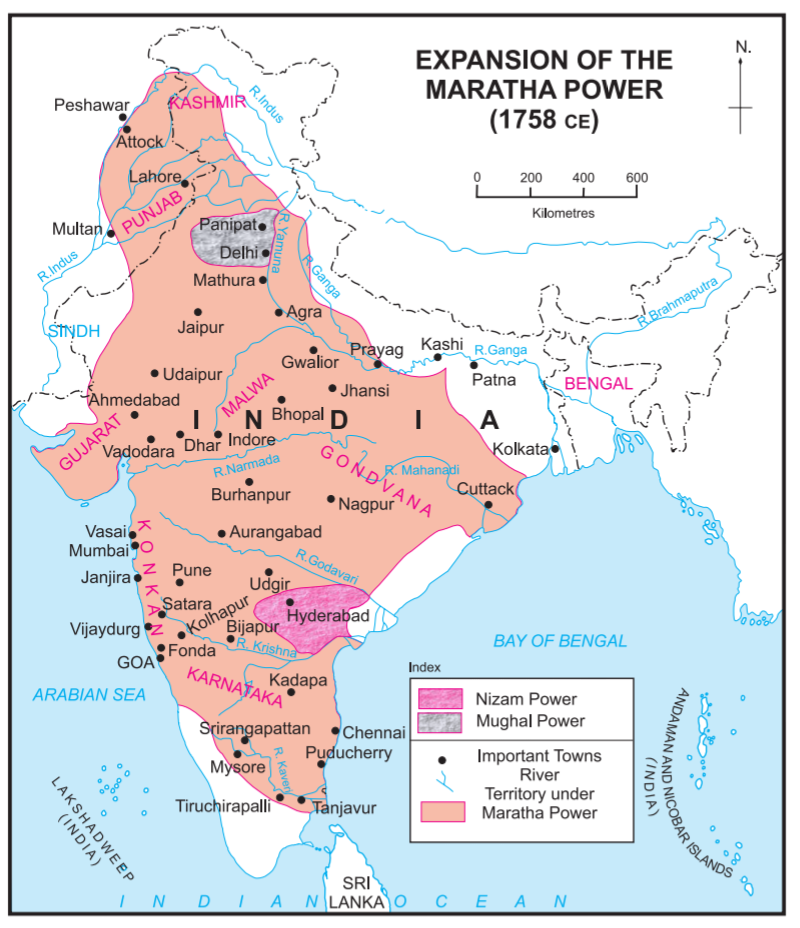

The Marathas of the 18th-century are different. They are recent enough that many people have personal family connections to this period and the people of this period. There is a concreteness. Though the Marathas are people of the Deccan, they are not totally alien to the Gangetic plain, sharing a broad civilizational identification. Additionally, despite Maharashtra being a caste-based state like all Hindu-majority states, there is a strong sub-national identity. Despite the prominence of Brahmin Peshwas, the Maratha Empire was driven at all levels by the manpower of the militarized rural peasantry.

The Maratha identity emerged out of decades of conflict and warfare. In classic cultural evolutionary terms, intergroup competition drove within-group cohesion. This is a well-known dynamic. War tends to solidify identity, contingent on the scale of the war. Even if the Marathas originally did not see themselves leading a pan-Indian cultural revolution with arms, that does seem to be what ended up occurring at the height of the Maratha Empire.

Their military aspect is also critical. The Bengal Renaissance led to a strong sub-national identity among Hindu Bengalis in particular, especially the elites. But civilian brilliance does not seem to have the power to ground a myth. That must be done with the sword (or musket).

Ultimately, national identity must be more than a negation. This is most clear in the nature of Pakistan vs. Bangladesh. Pakistan’s identity is much more rooted in its negation of Hindu India (along with its claim to be the heir of the Mughals). The people of the Gangetic plain resisted Islamicization, but much of their broader identity beyond community seem to be fixated on the negation and rejection of the Islamic period.

The Maratha example is one which is not founded on negation, but creation. That creation occurred out of the maelstrom of decades of warfare and conflict. But it did occur. War led to the creation of the skeleton of an Empire based on Indian cultural motifs, without West or Central Asia ties.

The Maratha Empire was ultimately incomplete. The British stopped what was likely an inevitable deposition of the Mughals and a decentering of Islam as the obligate religious-identity at the apex of political power in the subcontinent. But it is a realized enough history that can serve easily as the seed for a future identity.

I periodically get inquiries on various issues relating to the genetic position/relatedness of various “communities” in the Indian subcontinent. Thanks to the

I periodically get inquiries on various issues relating to the genetic position/relatedness of various “communities” in the Indian subcontinent. Thanks to the

This episode is a bit of a “brocast”, as Razib, Mukunda, and Suraj, a Bengali, and two Tam-Brahms, talk about being dark-skinned and South Asian. But there are lots of other topics that were touched upon.

This episode is a bit of a “brocast”, as Razib, Mukunda, and Suraj, a Bengali, and two Tam-Brahms, talk about being dark-skinned and South Asian. But there are lots of other topics that were touched upon.