From my Substack:

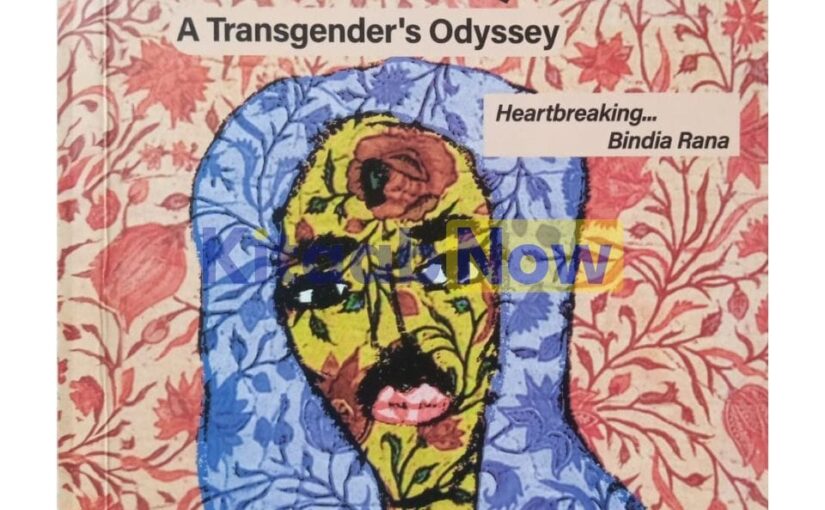

Queen Zarqa: A Transgender’s Odyssey (Lightstone Publishers 2025) is an English translation from the Urdu of a novel by Hayat Roghaani. Roghaani originally wrote the novel in Pashto. It was then translated into Urdu by Gohar Rehman Naveed and subsequently into English by Shama Askari. It is noteworthy for being one of the few Urdu novels to deal with the subject of khawaja saras–transgender women (also referred to as hijras in India). 1

In her “Introduction” to the book, Zubaida Mustafa–a renowned Pakistani journalist who passed away earlier this year–describes how the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act 2018 “grants [transgenders] the same rights as any other citizen of Pakistan. Recognizing their special needs the Act provides for separate transgender wards in hospitals. True as is the wont in this country many of the facilities promised under the law have yet to see the light of day, but activism, cajoling the authorities and other means could bear fruit” (20).

Mustafa goes on to describe attempts to roll back the protections granted by the 2018 act. She writes:

But what is more disturbing is the concerted drive by some bigoted and misogynist leaders of religious political parties to undo the gains the transgender persons have won. These parties have already got the Shariat Court to give a verdict adding conditionalities that offend the dignity of transgender persons. The Shariat Court wants transgender persons to appear before a medical board to have their gender determined. The government has mercifully appealed to the Supreme Court against this judgement. The final verdict is still awaited,and the Shariat Court’s ruling is held in abeyance until the Supreme Court rules on the matter (20).

Given the immense challenges faced by transgenders in Pakistan and the sensitivity of this subject, it is extremely commendable of Roghaani to take up this subject in his fiction. While the novel is not great literature by any means, it serves an important sociological function in sensitizing readers to this important subject.

The novel tells the story of Zeerak Khan (later known as Zarqa) from his birth in an unnamed village in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK). Zeerak is effeminate from a young age. The narrator notes:

Firduous was four years older than Zeerak, but Zeerak had never been his playmate. Nor had he played with marbles or a slingshot–he mostly played with Kameelai his cousin. Games of blind man’s buff, or they played with dolls, and often their game was to set up house. He told Kameelai, ‘You will enter the house like a man, and I will serve you dinner.’

‘No, I am a girl, and I will be a woman who will serve you dinner.’ (56).

Later, in adolescence, Zeerak is sexually assaulted by his cousin Firdous Khan. The narrator writes:

…Firdaus Khan had long passed the age of playing with toys. Now he wanted toys that were alive, those that walked and talked, and had warm, beautiful bodies. He reached out his hand towards Zeerak Khan. A bandit was after all, a bandit. What would you call a protective hedge that enclosed a field, which one day turned and devoured its own produce?

All the lust and desire that had gathered in his eyes slowly moved down into his hands. Zeerak Khan had curled into himself like a frightened fawn; his mind was wandering, and bits of memory were creeping back. The hungry, greedy eyes of the village boys and Mohabbatai’s thirsty lips… He was acceptable to both because he had been created with such clay that he was attractive to both sexes and he was weary of both. He tried to dissuade Firdaus and turned away; Firdaus did not stop. When Zeerak could not outmaneuver him, he got off the charpoy and stood by the door. In the darkness, he desperately looked for a glimmer of light (67).

Zeerak eventually leaves home with a family friend for Karachi where he joins a group of khawaja saras and assumes the new identity of Zarqa. While he finds a new accepting community, he also faces exploitation by customers including a rich Seth (businessman). Roghaani doesn’t shy away from depicting the abuse that transgenders face from their customers and from the wider society.

In conclusion, Queen Zarqa serves an important purpose in sensitizing Pakistani readers to the plight of the transgender community. Shama Askari deserves appreciation for her accessible and readable English translation. I would recommend the novel to all those interested in issues of gender and sexuality in Pakistan.

For more detail on khawaja saras, see my essay The Hijras of India