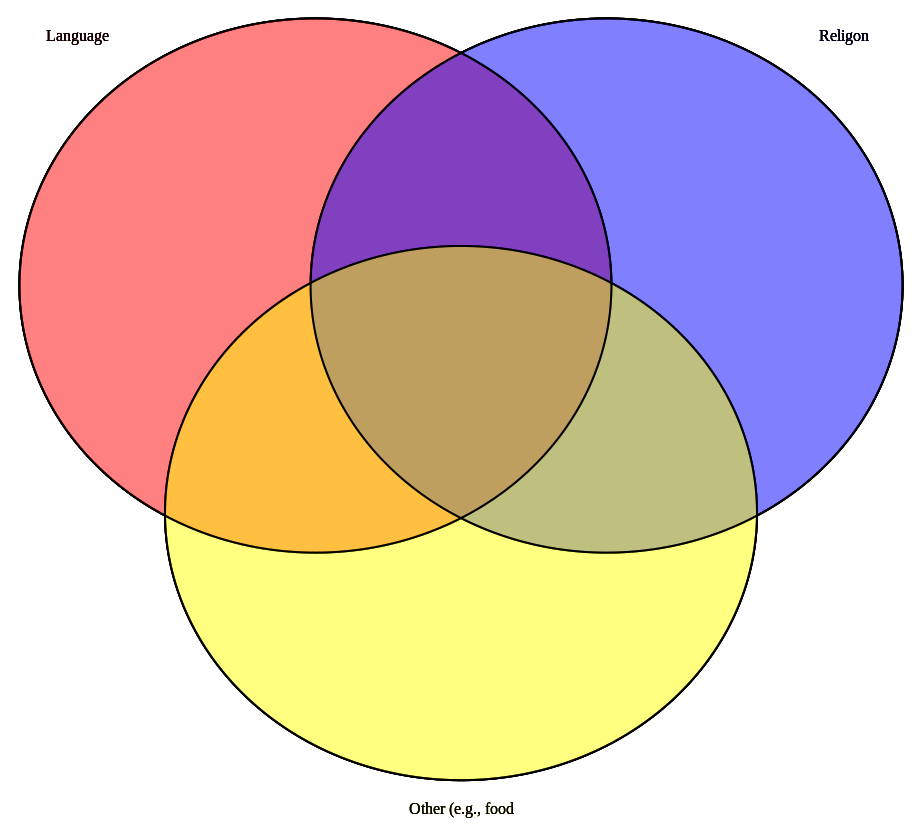

A really strange conversation on ethnicity broke out below. The primacy of lots of different variables was argued.

My family arrived in the USA ~1980 when there were not too many South Asians compared to today. Additionally, they have lived in major urban areas, small towns, and medium-sized cities. My parents grew up in (East) Pakistan, married and had their first children in Bangladesh, but have spent most of their lives now in the United States of America. Both speak English with a strong accent and are moderately religious Muslims. You wouldn’t call them secular, but neither are they visibly or ostentatiously Muslim. In American politics, they are staunch Democrats, while if they have an opinion on Bangladeshi politics they are Awami League (the ratio of discussion of American to Bangladesh politics in my family growing up was about 100 to 1 in favor the former).

Today my parents’ social circle, in a relatively large urban area, are Bangladeshis. Most of these people (almost all in fact) arrived in the United States much later than they did. But in the 1980s my parents had a much smaller pool of social acquaintances who were Bangladeshi. In the early 1980s, there were 15,000 Bangladeshis in New York City. Today there are probably closer to 200,000.

Here are some things I will observe in relation to my parents’ more diverse social circles in the 1980s. First, they were overwhelmingly South Asian. Those who were not South Asian were usually married in, and usually white. Second, a core group consisted of Bangladeshis. But the next group probably consisted by Indian Bengalis. A somewhat more established community. In fact, the boundary between Bangladeshis and Indian Bengalis were somewhat fluid. The two groups spoke the same language, and there was a large dietary overlap.

Next in order to the Indian Bengalis were a variety of other social clusters of South Asians that they met through various acquaintances and friends. For example, one cluster of friends consisted mostly of people from the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh, but with a large minority from other parts of India. Because there was ethnolinguistic diversity in this social group generally everyone spoke English, rather than Telugu, which was the most numerous language.

Another group consisted of people from Pakistan and Indian Muslims. This group also had some other token Bangladeshis. The unifying factor in this group was that all were South Asian Muslims. The de-unifying factor in this group is that the non-Bengalis would sometimes make the proactive case for Urdu as a unifying language, which my parents and the other Bengalis always objected to (because of their age, almost all the Bengalis in the group could follow the conversation in Urdu, since they grew up in Pakistan).

One issue in social circumstances with Pakistanis is that my parents found the food less palatable. This was a very important criterion for them for social interactions and a primary reason why sometimes they preferred going to parties thrown by their Hindu Bengali friends in preference to their Pakistan Muslim friends. By “less palatable”, I mean here that Pakistani cuisine was not “comfort food” for them.

My parents went to a multi-ethnic mosque several times a year. From what I could tell the South Asians kept to themselves, the Arabs kept to themselves, the Turks kept to themselves, etc. There was no real deep interaction. My parents never had any close Muslim friends who were not South Asian. In fact, we went to dinner with Chinese people (my father’s colleagues) more often than we went to dinner at a non-South Asian Muslim’s house.

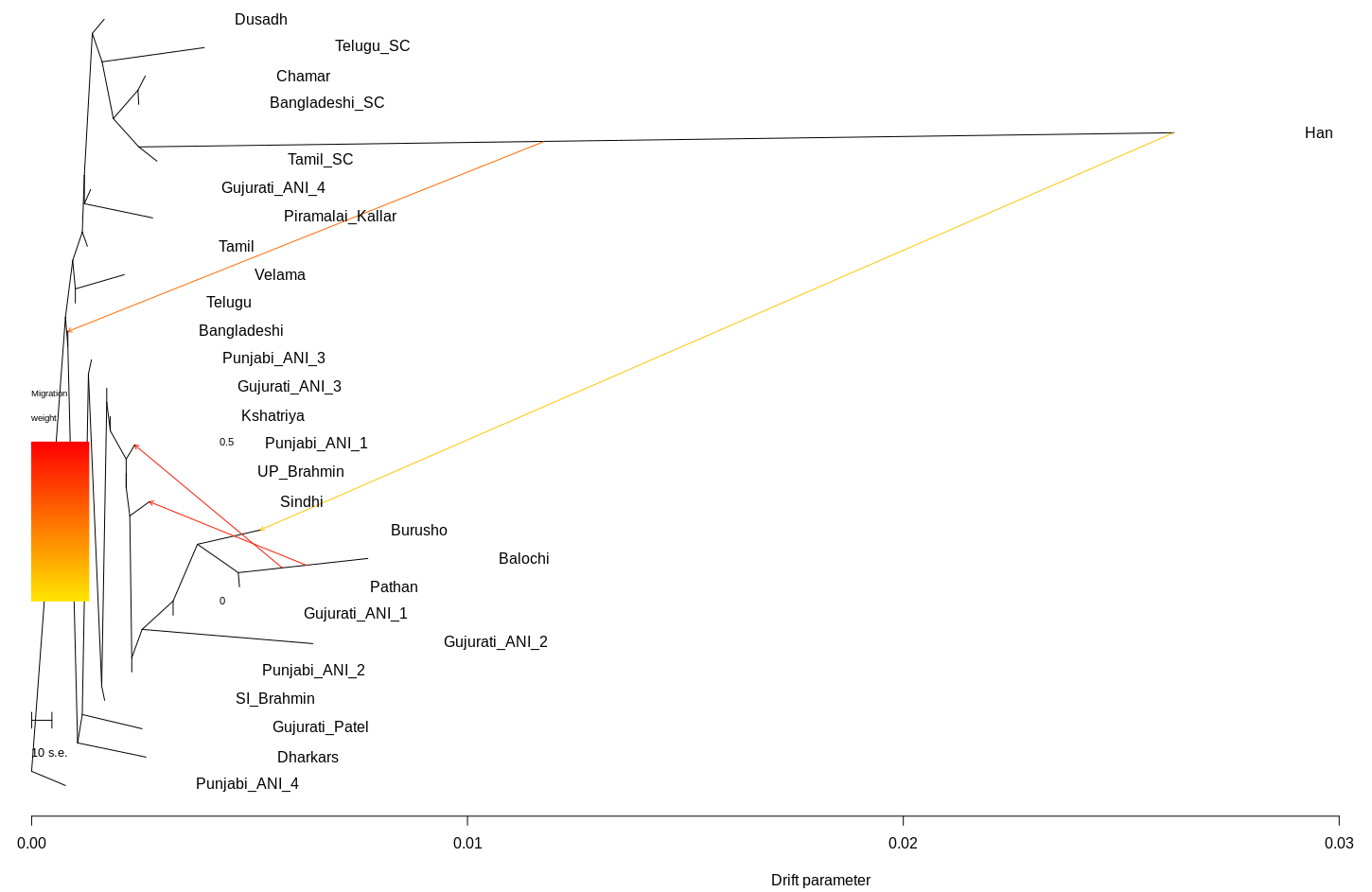

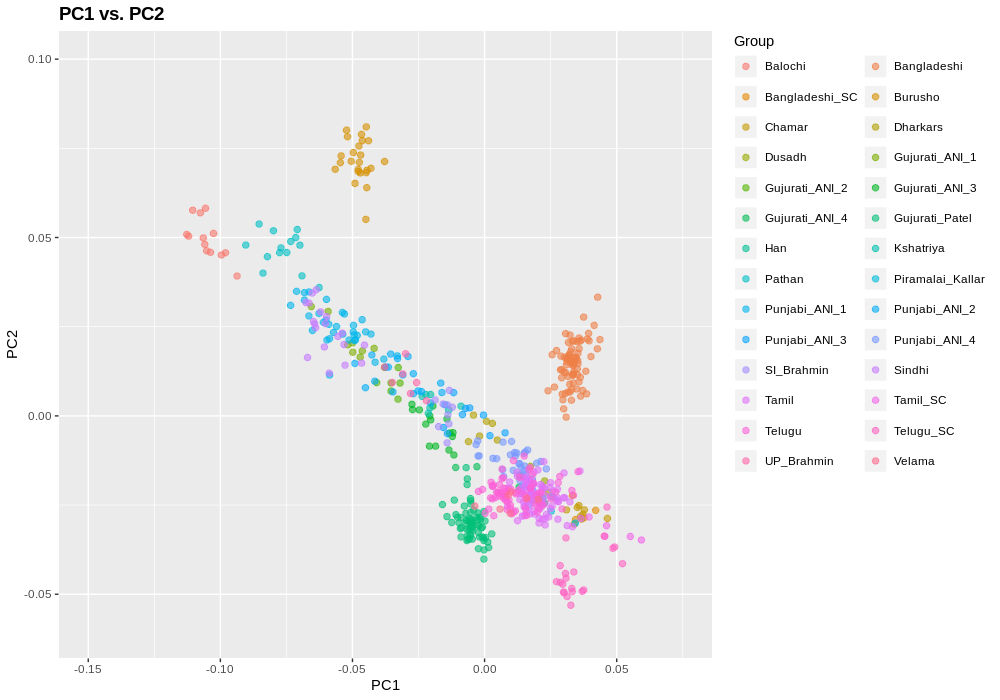

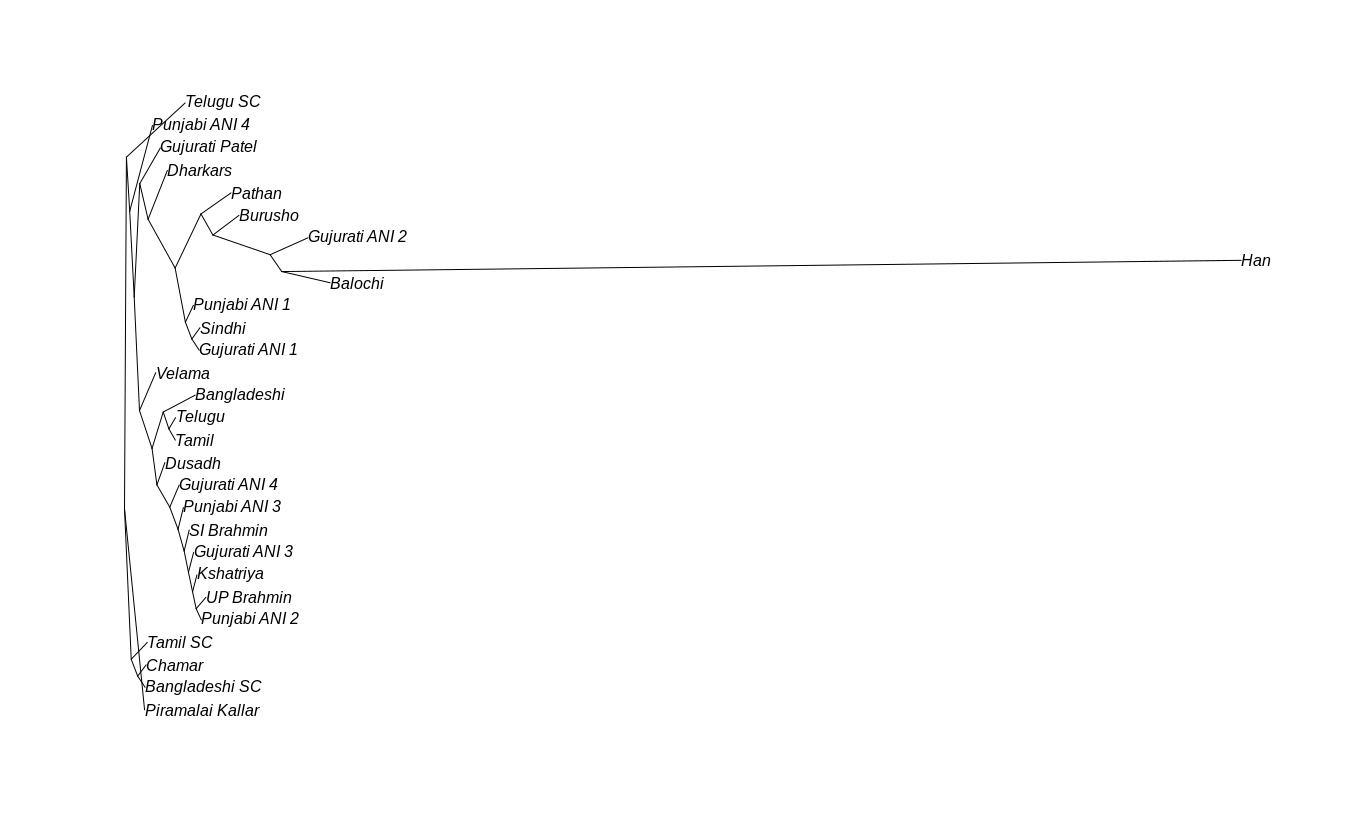

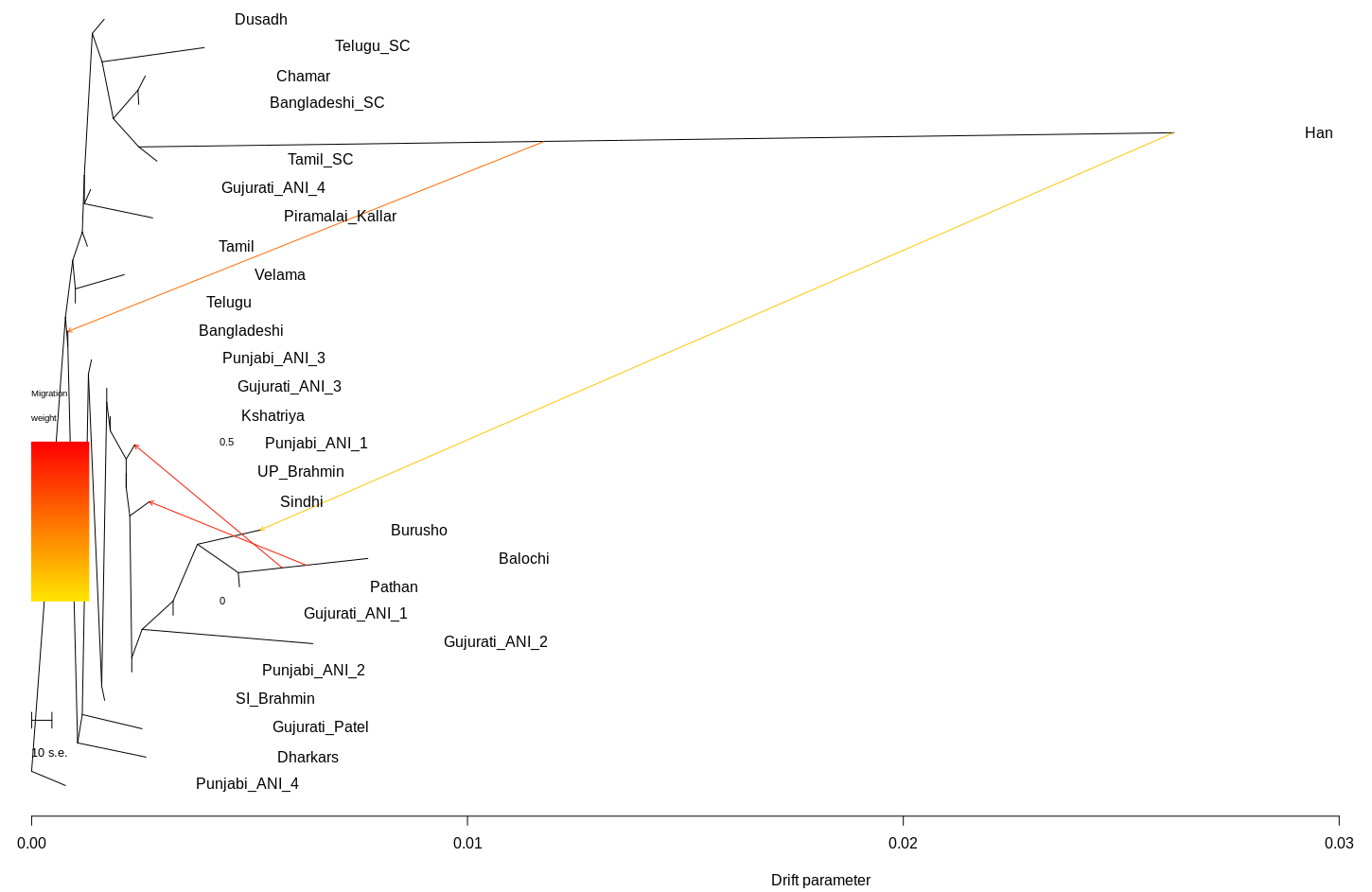

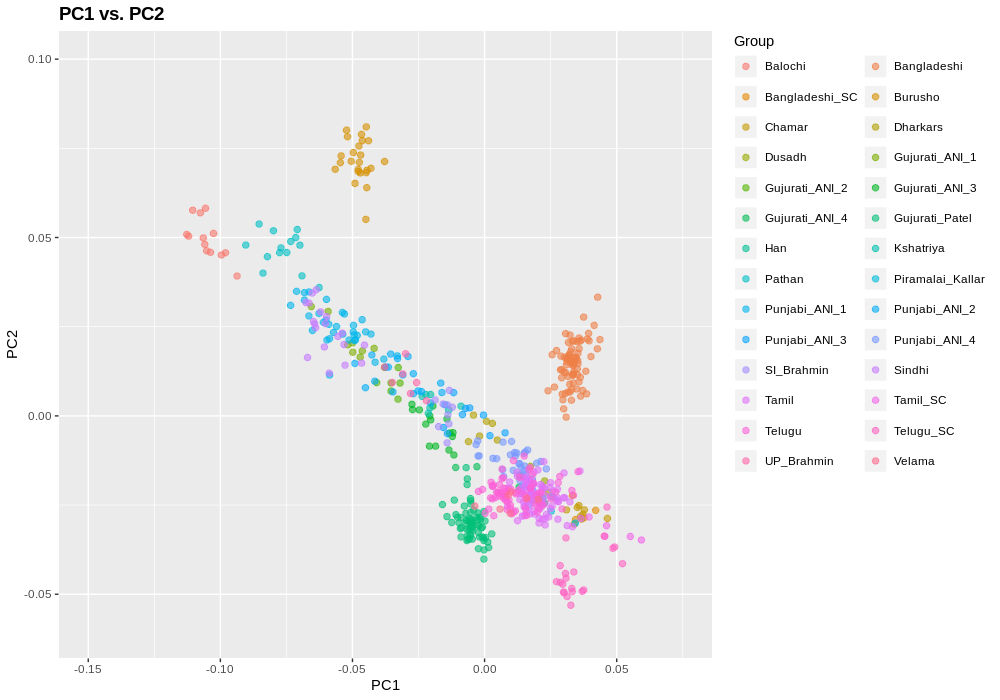

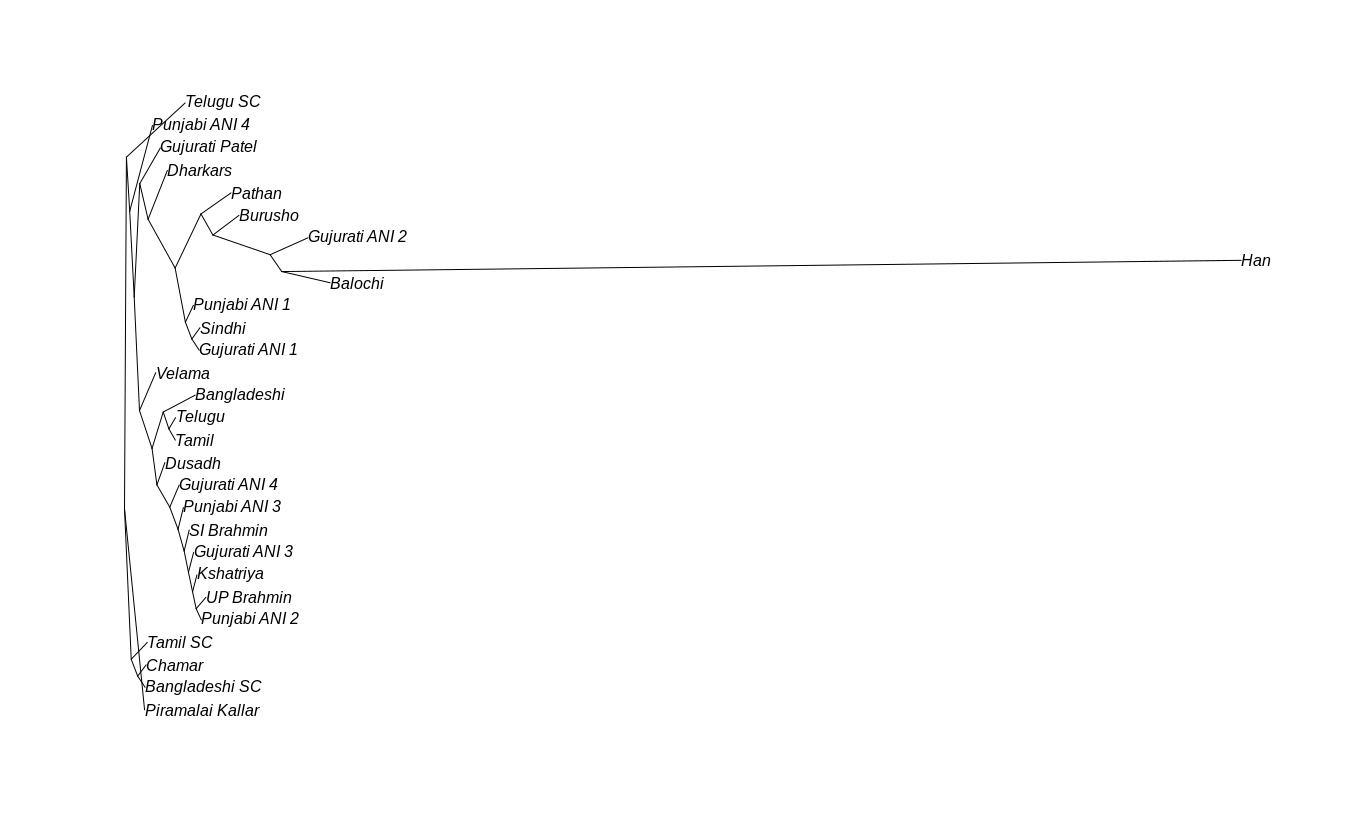

That’s about it from me. Below are some genetic plots.