Since we are discussing caste, this post from my Substack seems relevant. This review was originally published on “The South Asian Idea” in January 2018.

One of the frequent topics of debate among those interested in South Asia is the caste system and whether it is unique to Hinduism or features in other South Asian religions as well. Hindu society has traditionally been divided into four castes (or varnas): Brahmins (priests), Kshatriyas (rulers, administrators and warriors), Vaishyas (merchants and tradesmen), and Shudras (artisans, farmers and laboring classes). A fifth group consists of those who do not fit into this hierarchy at all and are considered “untouchable”. What separates caste from other systems of social stratification are the aspects of purity and ascribed status. Upper-castes consider lower castes to be “impure” and have rigid rules about the kind of social interaction they can have with them. For example, upper castes will not accept food from those of a lower caste, while lower castes will accept food from those above them. Caste status is also ascribed at birth and has nothing to do with an individual’s achievements. A Brahmin peasant remains a Brahmin while an “untouchable” engineer is still an “untouchable”. This system persists in India today, though the government does provide affirmative action in order to uplift members of “backward” castes.

Coming from a Pakistani background, I was not familiar with the operation of the caste system in daily life. Though Pakistan is a highly socially stratified society, this system has no religious sanction. In Islam, all believers are considered equal in the eyes of Allah. Unlike in India, where until recently, “untouchables” could not go into several temples, all social classes pray together in the same mosques. This fact is highlighted in one of the famous couplets from Allama Iqbal’s poem “Shikwa” (the complaint) which states: “Ek hi saf mein khare ho gaye Mahmood-o-Ayaz/ Na koi banda raha aur na koi banda nawaz” (Mahmood the king and slave Ayaz, in line as equals stood arrayed/ The lord was no more lord to slave: while both to the One Master prayed). At least in religious terms, one Muslim is not better than any other, no matter what his social status. Of course, this does not mean that social stratification ceases to exist. To this day, rich Pakistani families have separate utensils in their homes which are to be used by the servants. Punjabi Christians who engage in janitorial work are still known as “chuhras”, a derogatory reference to their pre-conversion caste status as “untouchables”. However, unlike the Hindu caste system, social class in Pakistan is not based on ascribed status. If someone from a low socio-economic background attains an education and a well-paying job, he or she will no longer be treated as belonging to their previous socioeconomic group. This is a major difference from India, where one’s caste remains salient, no matter one’s economic status.

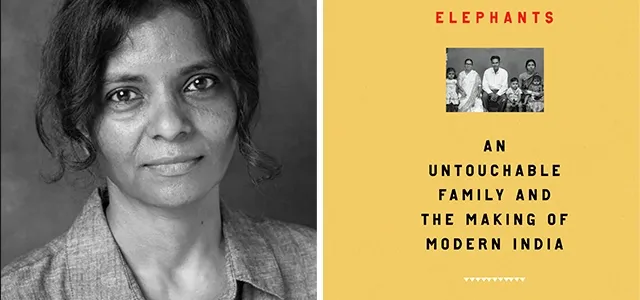

A first hand account of caste in India is given in Sujatha Gidla’s recent book “Ants Among Elephants: An Untouchable Family and the Making of Modern India”. Gidla was born into an “untouchable” family in the southern Indian state of Andra Pradesh. Through the story of her ancestors, she presents a portrait of India from the end of British rule to the 1990s. It is particularly interesting to note that while her family is Christian (a religion in which there is technically no caste), they are still considered “untouchable” in Hindu society. Gidla writes: “Christians, untouchables—it came to the same thing. All Christians in India were untouchables, as far as I knew (though only a small minority of all untouchables are Christian.) I knew no Christian who did not turn servile in the presence of a Hindu. I knew no Hindu who did not look right through a Christian man standing in front of him as if he did not exist. I accepted this. No questions asked” (Gidla 5). Caste is so pervasive in India that it applies even to those groups whose religions formally believe in equality.

Another aspect that differentiates Gidla’s family from that of the typical “untouchable” is their educational attainment. Starting with her grandparents’ generation, her family was educated in missionary schools. Gidla herself studied engineering in India and then moved to the United States for further education. However, these educational achievements did not stop the family from experiencing discrimination based on their caste. After Gidla’s mother, Manjula, passed the exams that qualified her to work as a university lecturer, she was posted by the government to a distant town. When she got there, the principal of the college, a Brahmin woman, refused to let her take up her post. (243-244). Luckily, she was able to return to the job she had just left and her ex-boss was kind enough to rip up her resignation letter. This incident is just one example of the bigotry the family had to face.

Much of the book tells the story of Gidla’s maternal uncle Satyam who was engaged with the Communist Party from an early age and became one of the founders of the Maoist movement. However, caste remained salient even within the Communist movement. Gidla describes how new recruits were given jobs that reflected their caste status: “Barber-caste members were told to shave their comrades’ chins and washer-caste members to wash their comrades’ clothes. Untouchables, of course, were made to sweep and mop the floors and clean the lavatories” (302). Even though Satyam had initially believed that the communist movement should not focus too much on caste, but on fighting for the rights of all workers, he eventually came to believe that upper-caste peasants and workers “couldn’t be won to a truly revolutionary program” (305). When he tried to advocate for the concerns of “untouchable” recruits, he was accused of trying to divide the party and expelled.

Gidla’s book is an illuminating and accessible read. Through the story of one family, she shows how the phenomenon of caste operates in modern India. The book is particularly important for those of us who live in India’s neighboring countries, where caste does not operate in the same way—or at least not to the same extent—as it does in India.

So is caste and/or jati a feature of indic society, or is it emanating from hindu doctrine? are there rules defined in each and every town and village, or is caste-aware behavior perpetuated as a sort of hidden hand, a quirk of the indic mind to to establish purity hierarchies?

I don’t think anyone can seriously argue that caste doesn’t emanate from Hindu doctrine. It is Hinduism that believes that Brahmins were born from Brahma’s head etc. The “Laws of Manu” are Hindu scripture. It is Hindus who came up with the concept of people being “touchable” and “untouchable”.

In contrast, Islam and Christianity are theoretically egalitarian religions. In these religions, the operative distinction is between believer/nonbeliever. However, as Gidla pointed out, in South Asia, even followers of these religions practice a type of caste system. As I mentioned, in Pakistan, Christians who engage in janitorial work continue to be referred to as “chuhras”. We know that they were Dalits prior to conversion. Pakistani Muslims have a concept of “biradari” or “zaat”. However, our religion doesn’t justify caste. All Muslims are theoretically equal in Allah’s eyes. That is the difference from Hinduism.