My piece Stark Truth About the Aryans is doing well. Pretty good feedback. Part 2 will be out in the next day or so.

Genetic ancestry changes in Stone to Bronze Age transition in the East European plain.

Update: part 2 is out.

My piece Stark Truth About the Aryans is doing well. Pretty good feedback. Part 2 will be out in the next day or so.

Genetic ancestry changes in Stone to Bronze Age transition in the East European plain.

Update: part 2 is out.

You can listen on Libsyn, Apple, Spotify, and Stitcher (and a variety of other platforms). Probably the easiest way to keep up the podcast since we don’t have a regular schedule is to subscribe to one of the links above!

In this episode we talk to Akshay Alladi, an Indian conservative. We talk about what it means to be an Indian conservative and Indian cultural and political issues in general. Check it out.

You can listen on Libsyn, Apple, Spotify, and Stitcher (and a variety of other platforms). Probably the easiest way to keep up the podcast since we don’t have a regular schedule is to subscribe to one of the links above!

In this episode (split into two parts) we talk to Tim Mackintosh Smith, author of “Arabs; a three thousand year history of peoples, tribes and empires“. We talk about his book and about Arab history and contemporary reality. Check it out..

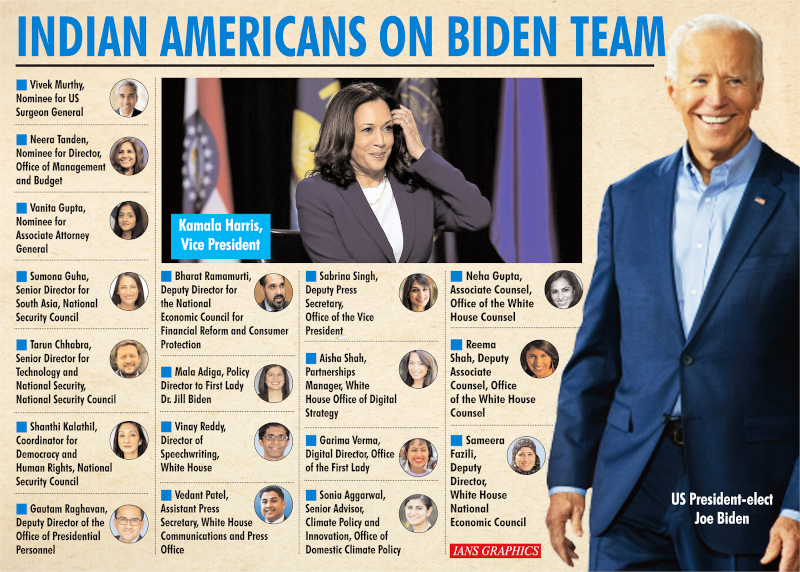

My Substack piece is up, Stark Truth About Aryans: a story of India. I’m pretty proud of this, as it wasn’t a single-sitting blog post, but something I worked over several times. Since it’s for paid subscribers I’ll post the first few paragraphs below, with an infographic that I think illustrates a lot of what’s going on.

Continue reading Stark Truth About Aryans: a story of India (part 1)

Peter Bellwood in First Farmers presents a hypothesis for the expansion of the Dravidian languages into southern India in the late Neolithic through the spread of an agro-pastoralist lifestyle through the western Deccan, pushing southward along the Arabian sea fringe. At the time I was skeptical, but now I am modestly confident that this is close to the reality.

Peter Bellwood in First Farmers presents a hypothesis for the expansion of the Dravidian languages into southern India in the late Neolithic through the spread of an agro-pastoralist lifestyle through the western Deccan, pushing southward along the Arabian sea fringe. At the time I was skeptical, but now I am modestly confident that this is close to the reality.

There is always talk about “steppe” ancestry on this weblog. But there are groups that seem “enriched” from IVC ancestry, as judged by the Indus Periphery samples. The confidence is lower since we don’t have nearly as good a sample coverage…but I think I can pass on what we’ve seen so far: groups in southern Pakistan, non-Brahmin elites in South India, and some Sudra groups in Gujarat and Maharashtra, seem to be relatively enriched for IVC-like ancestry. Then there is the supposed existence of Dravidian toponyms in Sindh, Gujarat, and Maharashtra. And, their total absence in the Gangetic plain.

There have been decades of debate about Brahui. I’ve looked closely at Brahui genetics, and they are no different from the Baloch. Combined with evidence from Y chromosomes (the Baloch and Brahui have some of the highest frequencies of haplogroups found in IVC-related ancient DNA), I doubt the thesis they are medieval intruders (if they are, their distinctive genes were totally replaced).

Genetically, we know that some southern tribes, such as the Pulliyar, have some IVC-related ancestry. But other groups, such as Reddy in Andhra Pradesh, have a lot more. How does this cline emerge? My conjecture is that there were several movements of “Dravidian” people from Sindh and Gujarat into southern India, simultaneous with the expansion of Vedic Aryans to the north into the Gangetic plain. The region the Vedic Aryans intruded upon, Punjab, was not inhabited by Dravidian speakers. Like Mesopotamia, the Indus Valley Civilization was probably multi-lingual, despite broad cultural affinities developed over time.

I was talking to a person of South Indian Brahmin origin today about their genetics. Over the course of the conversation, he showed me Y and mtDNA haplogroup types amongst his jati. The vast majority of the Y haplogroups were not R1a.

I was talking to a person of South Indian Brahmin origin today about their genetics. Over the course of the conversation, he showed me Y and mtDNA haplogroup types amongst his jati. The vast majority of the Y haplogroups were not R1a.

Brahmin groups in India seem to be about 15% to 30% steppe in their overall genome. But their Y chromosomes are usually 50% or so R1a1a-Z93. The lineage associated with Indo-Iranian pastoralists.

So what’s going on with the other haplogroups? For example, J2, L, C, G, and H?

From what I can see J2 and L are the next most frequent haplogroups after R1a1a-Z93. This tells us something. These are haplogroups found in ancient “Indus Periphery” samples. And, these two haplogroups are found at high concentrations in the northwest of the subcontinent.

It doesn’t take a {{{Brahmin}}} to connect the dots here. Some of the gotra as early as the Vedic period were almost certainly derived from high-status individuals in the post-IVC society. Warriors and priests in the fallen civilization of the IVC, which had likely degraded itself to a level of barbarism by the time the Indo-Aryans became ascendant.

I like to make jokes about “sons of Indra.” But let’s give the dasyu credit where it’s due: those Indians carrying J2 and L almost certainly descend from the men who build the great cities of yore. Their dominion was lost when their civilization fell, but they integrated themselves into the new order.

What’s going on?

I have a 6000-word piece on Indian genetics coming out on my Substak in the next few days (waiting on some maps that were commissioned).

Update: The pieces (had to break into two) are ready to go. Part 1 today and part 2 tomorrow. I commissioned some simple maps and created an infographic. Since these will be “paid” (you have to subscribe), I’ll post the infographic for people here:

When perusing Twitter I occasionally see arguments between the troll Araingang and contributors to this weblog on various topics. Many times I don’t really what the argument is about because I feel it’s deeply semantic.

When perusing Twitter I occasionally see arguments between the troll Araingang and contributors to this weblog on various topics. Many times I don’t really what the argument is about because I feel it’s deeply semantic.

So, for example, caste, varna, and jati. I know the dictionary definition of all this stuff and the various arguments. As an atheist, and someone who has “no caste” or varna or jati, I’m not very interested in theological arguments as to the origin of these concepts, their validity, and their application. Muslims for example can write 1,000-page books on Tawhid. I don’t care. What I care about is the application of Shariah law upon dhimmis and the heterodox. The rest is commentary.

In the 2000’s I read books such as Nicholas Dirks’ Castes of Mind: Colonialism and the Making of Modern India. The argument and evidence marshaled suggest that the raw materials of the caste system predate the British, but their system of manipulation, organization, and rationalization was critical.

Then, in the period after 2010, I began reading and analyze the genetic data. I was shocked at how clear and distinct varna and jati differences were. My friend Surya Yalamanchili sent me his DNA last year, and I asked him if he was Kamma. He had no idea what that meant, but the genetic evidence seemed persuasive to me from other people he clustered within my private data. He asked his mother, and she said “yes.” He was shocked. I was not.

The conclusion I draw from this, along with patterns such as higher steppe ancestry in “higher varna,” is that there are deep roots and structures to the inequality we see across the Indian subcontinent. It is possible that in fact, the jatis were “separate but equal.” But I doubt that just as I doubt the “peace” Islam imposed upon dhimmis was welcomed on the whole (in some cases, yes). Dalits in particular have very small effective populations. That means their genes show evidence of high levels of inbreeding because of incredibly small marriage networks.

This post is less about what I believe, then trying to understand what you know and believe. The genetic data is something I am familiar with. I work with it. The historical evidence I do not know. Were there Dalit kings? Were there long periods where Brahmins were subordinate as menial servants to Sudra jatis?

I understand that Hindus of a more progressive bent are uncomfortable with the association between caste and their religion and identity. Religion is what man makes it, and so I do not see its connection to Hinduism as necessary, ineluctable, and eternal. But, the impact of caste is so strongly stamped on the genes of so many Indians I cannot brush it away as a detail of history.

An old review I wrote (back in 2002) for the magazine Herald.

” The algorithm is …the second great scientific idea of the West. There is no third.”

This sentence at the very beginning of the book should warn us that this is not going to be science writing in the Asimov vein. Dr. Berlinski once boasted that he can be accused of many things, but shrinking from controversy is not one of them. A professor of mathematics, a novelist, something of a poet and the successful author of “a tour of the calculus”, Dr. Berlinski is also famous for his very public insistence that Darwinian evolution does not add up; that something is missing from the story and the high priests are engaged in a cover-up. In “the advent of the algorithm” he sets out to tell us about the algorithm: “a procedure, written in a symbolic vocabulary, that gets something done step-by-step without the need for any intelligent assistance”. But he ends by questioning the ability of science to explain the mind: the intelligence that fashions and uses these algorithms and infuses them with meaning.

The book begins and ends with Gottfried Leibniz. Between inventing the calculus, imagining the monads and carrying out his diplomatic duties, Gottfried Leibniz also laid the foundations of mathematical logic and the science of computing. He is followed by Guiseppe Peano, Gottlieb Frege, George Cantor and others, till we get to the great David Hilbert and his challenge to mathematicians to show that mathematics is consistent, complete and decidable (in principle, if not in practice). Within a few years, Kurt Godel was able to show that this is not possible. After an explanation of Godel’s revolutionary result, Alonzo Church, Alan Turing, Emil Post, Claude Shannon and others are introduced and the reader learns about the developments in logic and mathematics that form the foundations of our modern digital world.

Berlinski’s explanations of these developments are lucid, even brilliant, and someone with little mathematical knowledge beyond high school should still be able to understand what he is saying. But he does not want to stop at the bare bones of the theories. He is determined to give his readers a hint of the larger import of these matters, and he presses into service a number of stories, asides and literary flourishes. Sometimes the prose is so purple, it throbs and begs to be deflated, but the overall effect is not unpleasant. Here is a typical fragment about Liebniz:

“And then, by some inscrutable incandescent insight, Leibniz came to see that what is crucial in what he had written is the alternation between God and Nothingness. And for this, the numbers 0 and 1 suffice.

Twinkies and Diet Coke in hand, computer programmers can now be observed pausing thoughtfully at their consoles.”

And here are the last days of Hilbert in Nazi Germany:

“Hilbert closed his remarks with words that were later inscribed on his tombstone: we must know. We will know.”

“We realize now that that was the last time those words could have been uttered without irony…the mathematicians who had heard his voice and fallen under his command had scattered, some going to the US or South America or even China, others, for all their sophisticated and intellectual cunning, finding themselves packed in freight cars, grinding their way to some place in the east.”

This powerful and humane sense of history and tragedy is accompanied by an almost wicked sense of humor and an absolute unwillingness to submit to fashionable opinion. The stories and asides are generally delightful, though the author could easily have spared us his own amorous adventures and multiple marriages without any loss to the book. The math is challenging, but not overwhelming and worth the effort to understand it. In the last chapters, he takes on the issue of whether the mind is simply an algorithm, albeit a very sophisticated one? The question is not if the mind uses algorithms or if many of its functions can be reduced to algorithms (it does, and they can). The 300-pound gorilla in the room is consciousness: an algorithm is merely symbols, manipulated according to rules (themselves strings of symbols) but an intelligence creates those symbols and assigns them meaning. When the mind sees, something is seen by someone. Who is this someone who sees? Berlinski knows that even the scientists do not know the answer to that. The attack on scientific monotheism in the last chapters may upset those who suspect that such “attacks from within” will provide ammunition to those who wish to bludgeon us into more extreme monotheisms of their own. But Berlinski believes that doubt has brought us this far, it is too late in the day to stop. All the emperors are naked, why should the emperor of science get special treatment? And so he ends with Heraclitus:

”you could not discover the limits of the soul, not even if you traveled down every road. Such is the depth of its form”