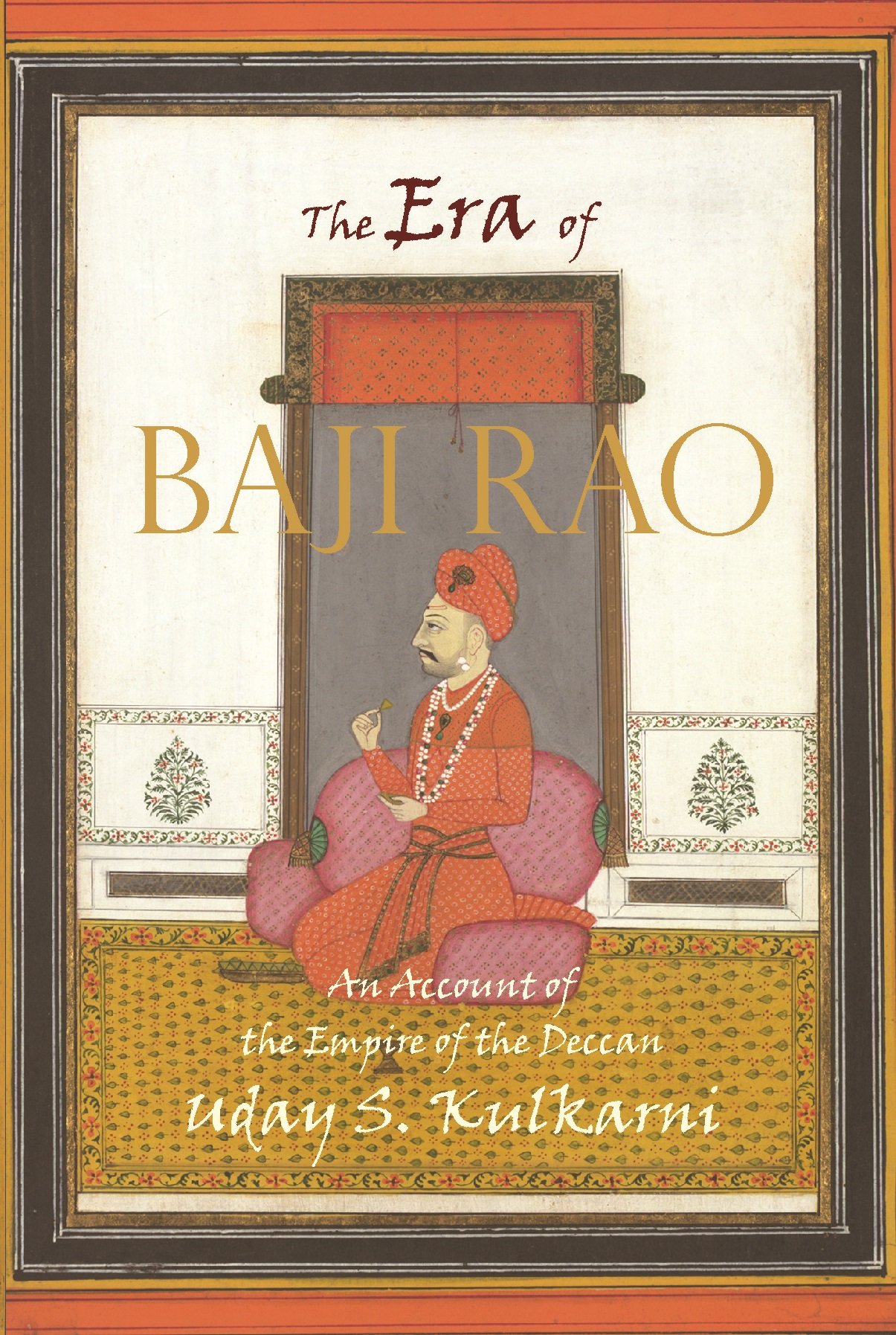

Jadunath Sarkar, the preeminent historian of Maratha history states

The place of Bajirao I in India’s history comes home to us with unmistakable force and vividness when we compare the political situation of this country in the 1740 to that in 1720.

In 1720, Marathas were a small state spread over a few districts in western Maharashtra rife with internal divisions, while by the end of 1740 Marathas were the largest power in the country which covered lands from the Tungabhadra to the Yamuna. This was largely due to the unbeaten generalship of Peshwa Bajirao I. Uday Kulkarni, a Doctor by training, has taken to history writing these last few years and his writing has been a refreshing counter to the narrative-focused history popular in recent times. Dr. Kulkarni goes through the original sources as methodically and systemically as a surgeon would and the result is a crisp, tight book grounded in documents and not a narrative/hagiography held together by the whims of the author.

The tale starts with the Maratha-Mughal war of the late 17th century and ends with the death of Bajirao. The river Narmada or Rewa is the voice of the book as Rewa Uwaach, as Bajirao’s life was witnessed by the river Narmada, from his earliest campaigns to his untimely death. A few relationships and characters from this time period stand out in the book, and I got to know some interesting facets of all these characters and their actions in the book.

The Aurangzeb – Shahu relationship, its genesis, and its implications have been well represented in the book. Whether it was due to remorse, realpolitik, or human nature but Aurangzeb had treated Shahu well in captivity and Shahu’s unwillingness to directly attack the legacy of Emperor Aurangzeb is one of the most under-explored parts of Maratha history. This facet of Shahu can be seen as a constraint on the ambitions of the dynamic Peshwa.

Kulkarni presents the Era of Bajirao as a rivalry between two generals, Nizam-Ul-Mulk – one of the last generals from the time of Aurangzeb &Bajirao. Bajirao’s victories over the Nizam, both military and diplomatic are covered very well in the book.

The author also sheds light on a not very known fact about the life of Bajirao – his troubles with debt. The letters exchanged between Bajirao, Chimaji Appa, Brahmendra Swami, and Shahu Maharaj all point to the constant financial pressure under which the Peshwa operated. The strain between the Emperor and his prime minister over various issues, from financial matters to Bajirao’s conquering zeal are all brought forth.

The Konkan campaigns of the Peshwa, against the Siddis and the Portuguese, take up a considerable amount of the book. Chimaji Appa, the hero of the wars with the Portuguese who has often been ignored by popular imagination gets his due. The episode of Mastani is dealt with without unwarranted speculations or folk gossip. The fascinating character of Brahmendra Swami is always present in the background as Bajirao and co’s spiritual mentor.

Kulkarni also differentiates the ethics & morality of the Marathas – especially under Bajirao and Chimaji from their enemies with examples like Bajirao’s decision of not mauling Delhi and Chimaji’s respectful treatment of the Portuguese (especially women).

Bajirao’s singular quality in Kulkarni’s view is

Flight in the face of a strong enemy was not considered an act of cowardice, it was never the intention of the Maratha troops to give battle in an unfavorable situation. Bajirao’s success lay in his ability to choose when to fight, where to fight (and more importantly) when not to.

The only issue a reader might have with the book is arguably also the book’s strongest quality – the author’s unwillingness to speculate beyond a reasonable point. As a reader, at many places, I felt that I wouldn’t mind going a bit deeper into the motivations and implications of the actions of the book. But all these issues are compensated easily by the treasure trove of letters, accurate maps (with military movements), and illustrations offered in the book. On the whole, I would rate the Era of Bajirao 5/5 and would highly recommend it to anyone interested in Indian history. It is especially a must-read of every Marathi Manoos – given the profound implications, the life of Bajirao had on Maharashtra. It is quite feasible, that without Bajirao’s and Chimaji’s rescue of North Konkan from the Portuguese, we might have even had a Portuguese governed Konkan (like Goa).

Dr. Kulkarni has also written some more books – including the Solstice of Panipat & and a book on James Wales – the Artist & Antiquarian in the time of Peshwa Sawai Madhavrao. His upcoming book – the Incredible Epoch of Nanasaheb Peshwa starts where he left off in the Era of Bajirao. Sadly none of these books are available in digital format and might be difficult to obtain abroad. For those who can’t get their hands on the book, you might be interested in the following for time being.

BAJIRAO PESHWA – THE EMPIRE BUILDER