“The artist is not a special kind of person; rather each person is a special kind of artist” Ananda Coomaraswamy, A pioneer historian of Indian Art and foremost interpreter of Indian culture to the West’.

Ananda Coomaraswamy: The Arts and Crafts of India and Ceylon (1913) not really a review but excerpts from the book. Very readable and not just the art but the religious and philosophical background to art. This and other books by AC are available free, link at end of the post.

Ananda Kentish Coomaraswamy (1877-1947)

Son of Sir Muttu Coomaraswamy the first Ceylon (and South Asian?) Knight and Elizabeth Beeby, who was a Lady-in-Waiting to Queen Victoria. First class honours in Geology and Botany (1900) from University of London. The first Director of Mineralogical Surveys, Ceylon (1903). Doctor of Science degree from the University of London in 1906 for identifying and research on the mineral Thorianite.

In 1905 he founded the Ceylon Social Reform Society. The Society was “formed in order to encourage and initiate reform in social customs amongst the Ceylonese, and to discourage the thoughtless imitation of unsuitable European habits and customs”. He claimed fluency in 36 languages, where his definition of fluency in a language is the ability to read a scholarly article without referring to a dictionary.

AC refused to join the British armed services in World War I and As a result he was exiled from the British Empire and a bounty of 3000

Pounds placed on his head by the British Government and his house was seized. Moved to USA in 1917 together with his extensive art collection, described as ‘among the finest in the Western world’. His entire private art collection was transferred to Boston Museum of Fine Arts, and worked there as Curator and as Visiting Lecturer at nearby Harvard University for the next thirty years until he retired in 1947.

AC’s first book major book Medieval Sinhalese Art was self published. Using his considerable inherited wealth bought the ailing Essex House Press and a small church called Norman Chapel in Broad Campden in Gloucestershire. He used part of the premises as his residence and moved the machinery of Essex House Press to the rest of the building.

Hand printing of the book started in September 1907 and was completed in December 1908. The layout of the book, which is a work of art in its

own right, and the printing of the 425 copies were supervised by him.

(more and much of above from In Appreciation of Ananda Kentish Coomaraswamy)

Excerpts from Ananda Coomaraswamy: The Arts and Crafts of India and Ceylon (1913)

In the first place, almost all Hindu art (Brahmanical and Mahayana Buddhist) is religious. ” Even a misshapen image of a god,” says Sukracharya {ca. 5th century a.d.) “is to be preferred to an image of a man, howsoever charming.” Not only are images of men condemned, but originality, divergence from type, the expression of personal sentiment, are equally forbidden. “(Animagemade) according to rule (shastra) is beautiful,no other forsooth is beautiful.

” the likeness of the seated yogi is a lamp in a windless place that flickers not”{Bhagavad Glta, vi. 19). It is just this likeness that we must look for in the Buddha image, and this only. For the Buddha statue was not intended to represent a man ; it was to be like the unwavering flame, an image ofwhat all men could become, not the similitude of any apparition (nirmanakaya).

A like impersonality appears in the facial expression of all the finest Indian sculptures. These have sometimes been described as expressionless because they do not reflect the individual peculiarities which make up expression as we commonly conceive it.

This ideal is described in many places, typically, for example, in the Bhagavad Gita xi. 12-19 : ” Hateless toward all born beings, void of the thought of I and My, bearing indifferently pain and pleasure, before whom the world is not dismayed and who is not dismayed before the world; who rejoices not, grieves not,desires not; indifferent in honour and dishonour, heat and cold, joy and pain; free from attachment”—such an one is god-like,from attachment”—such an one is god-like,

BhagavadGita is also the chief gospel of action without attachment: change, says Krishna, is the law of life, therefore act according to duty, not clinging to any object of desire, but like the actor in a play, who knows that his mask {persona) is not himself. For this impassivity is not less characteristic of the faces of the gods in moments of ecstatic passion or destroying fury, than of the face of the stillest Buddha. In each, emotion is interior, and the features show no trace of it: only the movements or the stillness of the limbs express the immediate purpose of the actor.

This amazing serenity (shdnti) in moments of deepest passion is not quite confined to Indian sculpture: something very like it, and more familiar to Western students, is found in the gracious and untroubled Maenad furies of the Greek vases, the irresponsible and sinless madness of the angry Bacchae.

|

| Maenad Satyr-Vase 480bc |

There is no more remarkable illustration of the Hindu perception of the relative insignificance of the individual personality, than the fact that we scarcely know the name of a single painter or sculptor of the great periods: while it was a regular custom of authors to ascribe their work to better-known authors, in order to give a greater authority to the ideas they set forth.

This process of intuition, setting aside one’s personal thought in order to see or hear, is the exact reverse of the modern theory which considers a conscious self-expression as the proper aim of art. It is hardly to be wondered at that the hieratic art of the Indians, as of the Egyptians, thus static and impersonal,should remain somewhat unapproachable to a purely secular consciousness.

Much later in origin are the definite Assyrianisms and Persian elements in the Asokan and early Buddhist sculpture, such as the bell-capital and winged lions.

Early Buddhism, as we have seen, is strictly rationalistic, and could no more have inspired a metaphysical art than the debates of a modern ethical society could become poetry. The early Sutras, indeed, expressly condemn the arts, inasmuch as ‘ ‘form, sound, taste, smell, touch, intoxicate beings.” It is thus fairly evident that before Buddhism developed into a popular State religion (under Asoka) there can hardly have existed any “Buddhist art,”

A confusion of two different things is often made in speaking of the subject-matter of art. It is often rightly said, both that the subject-matter is of small importance, and that the subject-matter of great art is always the same. In the first case, it is the immediate or apparent subject-matter—the representative element—that is spoken of; it is here that we feel personal likes and dislikes. To be guided by such likes and dislikes is always right for a practising artist and for all those who do not desire a cosmopolitan experience ; and indeed, to be a connoisseur and perfectly dispassionate critic ofmany arts or religions is rarely compatible with impassioned devotion to a single one.

The paintings of Ajanta, though much damaged, still form the greatest extant monument of ancient painting and the only school except Egyptian in which a dark-skinned race is taken as the normal type.

|

| Ajanta Painting |

|

| Ajanta Painting |

|

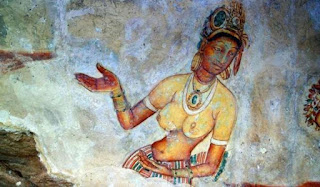

| Painting/fresco, approx 500 AD Sigiriya, Sri Lanka |

When a little later we meet with the excavated chatiya-houses, and, later still, the earliest Hindu temples of the Aryavarta and the Dravidian school, we are again faced with the same problem, of the origin of styles which seem to spring into being fully developed. . It is clear that architecture had not made much progress amongst the Aryans when they first entered India; on the contrary, all the later styles have been { clearly shown to be developments of aboriginal and non-Aryan structures built of wood(posts and beams, bamboo, thatch), the intermediate stages being worked out in brick. The primitive wooden and brick building survives to thepresent day side by side with the work in stone, a silent witness of historic origins. Some of the details of the early stone architecture point to Assyrian origins, but this connection is, for India, prehistoric. How the use of stone was first suggested is a matter of doubt; none ofthe early forms have a Greek character, but are translations of Indian wooden forms into stone; while stone did not come into use for the structural temples of the Brahmans until so late as the 6th century A. D.

The Ceylon Shilpashastras preserve canons of form and proportion for six different types, called by such names as Bell-shape, Heap of rice, Lotus, and Bubble.

|

| Chaitiya Hall (approx 50 AD), Karli, India |

Another most important class of early buildings, and one purely Buddhist, is that of the chaitiya-hall (Buddhist temples).

The prototype perhaps survives in the dairy temple of the Todas. We are well acquainted with the structural peculiarities of the chatiya-halls, from the many examples excavated in solid rock. These have barrel roofs, like the inverted hull of a ship, with every detail of the woodwork accurately copied in stone. The earliest date from the time of Asoka(3rd century B.c.) and are characterised by their single-arched entrance and plain facade.

|

| Toda Hut |

Reservoirs: but it was only notably in Ceylon that there existed conditions favourable to the construction of very large works at a much earlier date. The largest of the embankments of these Ceylon reservoirs measures nine miles in length, and the area of the greatest exceeds 6000 acres (24 sq km). The earliest large tank dates from the 4th century B.C. What is even more remarkable than the amount of labour devoted to these works, is the evidence they afford of early skill in engineering, particularly in the building of sluices: those of the 2nd or 3rd century B.C. forming the type of all later examples in Ceylon, and anticipating some of the most important developments of modern construction. The most striking features of these sluices are the valve pits (rectangular wells placed transversely across the culverts and lined with close-fitting masonry), and the fact that the sectional area of the culverts enlarges towards the outlet, proving that the engineers were aware that retardation of the water by friction increased the pressure, and might have destroyed the whole dam if more space were not provided.but

There is scarcely any Hindu building standing which can be dated earlier than the 6th century a.d. without any trace of historic origins. The explanation of this circumstance is again to be found in the loss of earlier buildings constructed of perishable materials; all the greatarchitectural types must have been worked out in timber and brick before the erection of the stone temples which alone remain. One point of particular interest is the fact that the early temples of the gods, and prototypes of later forms, seem to have been cars, conceived as self-moving and rational beings.

and in another place, the whole city of Ayodahya is compared to a celestial car. The carrying of images in processional cars is still an important featurej of Hindu ritual. The resemblance of the Aryavarta shikhara to the bamboo scaffolding ofa processional car is too striking to be accidental. More than that,’ we actually find stone temples of great size provided with enormous stone wheels (Konarak, Vijayanagar) and the monolithic temples at Mamallapuram (7th century) (fig. 83) are actually called rathas, that is cars, while the term vimana, applied to later Dravidian temples, has originally the same sense, of vehicle or moving palace.

The greatest period of Indian shipbuilding, however, must have been the Imperial age of the Guptas and Harshavardhana, when the Indians possessed great colonies in Pegu, Cambodia, Java, Sumatra, and Borneo, and trading settlements in China, Japan, Arabia, and Persia.

Many notices in the works of European traders and adventurers in the 15th and i6th centuries show that the Indian ships of that day were larger than their own ; Purchas, for example, mentions one met by a Captain Saris in the Red Sea, of 1 200 tons burden, about three times the size of the largest English ships then made (161 1).Many notices in the works of European traders and adventurers in the 151!^ and i6th centuries show that the Indian ships of that day were larger than their own ; Purchas, for example, mentions one met by a Captain Saris in the Red Sea, of 1 200 tons burden, about three times the size of the largest English ships then made (1611).

It is worth while to remark that a good deal of the material used for dagger-handles and similar purposes is not Indian or African ivory, but is known as “fish-tooth,” most of it being really fossil ivory from Siberia. Old examples prove that there used to exist an overland trade in this material. Hippopotamus and walrus ivory may also have found its way to India by land routes.

The great majority of Indians wear cotton garments, and it is from India that all such names as chintz, calico, shawl, and bandana have come into English since the i8th century. Weaving is frequently mentioned in the Vedas. cotton, silk, and woollen stuffs in the epics. Silk was certainly imported from China as early as the 4th century B.C.,

Neither cotton-printing nor dye-painting are Sinhalese crafts. All the finer cloths found in Ceylon appear to be of Indian origin. There is evidence of several settlements of Indian weavers in Ceylon on various occasions.

The Mughal portrait style is scarcely clearly developed before the time of Jahangir (1605 to 1627). At its best it is an art of nobly serious realism and deep insight into~character7 at its worst, it is an art of mere flattery. Two works reproduced here, the Bodleian Dying Man (fig. 169) and the Ajmer portrait of Jadrup Yogi (fig. 170), stand out before all others in their passionate concentration.

(my sbarrkum note; if some one can send link to modern colored images, Jadrup Yogi or Dying Man very welcome)

List of free books by Ananda Coomaraswamy

https://archive.org/search.php?query=Ananda%20Coomaraswamy