In Who We Are and How We Got Here one of the things that David Reich states is that while China consists to a great extent of one large ethnic-genetic group, India (South Asia) is a collection of many ethnic-genetic groups. To some extent, this is not entirely surprising. People from the far south of the subcontinent look very different from people from Kashmir or Punjab.

In Who We Are and How We Got Here one of the things that David Reich states is that while China consists to a great extent of one large ethnic-genetic group, India (South Asia) is a collection of many ethnic-genetic groups. To some extent, this is not entirely surprising. People from the far south of the subcontinent look very different from people from Kashmir or Punjab.

But that’s really not what Reich is talking about. People in Hebei look quite different from people in Guandong. Perhaps less different than a Tamil from a Kashmiri, but still quite different. But these regional differences grade into each other along a cline.

South Asia is different because strong genetic structure persists within regions. Both Tamil and Bengali Brahmins share some distinctive genes with local populations, but genetically they’re still a bit closer on the whole to Brahmins from Uttar Pradesh (I say this because I’ve looked at a fair number of genotypes of these groups). Similarly, Chamars from Uttar Pradesh and Dalits from Tamil Nadu share more with each other than either do with Brahmins from their own regions (though again, Chamars share more with Brahmins from Uttar Pradesh than Dalits from Tamil Nadu, in part because of gene flow from Indo-Aryan steppe pastoralists into almost all non-Munda people in the Indo-Gangetic plain).

When I read Castes of Mind: Colonialism and the Making of Modern India in the middle 2000s it seemed a persuasive enough argument to me. I had read other things about caste during that period, by both Indians and non-Indians. The authors were historians and anthropologists and emphasized the cultural and social preconditions variables shaping the emergence of caste..

When I read Castes of Mind: Colonialism and the Making of Modern India in the middle 2000s it seemed a persuasive enough argument to me. I had read other things about caste during that period, by both Indians and non-Indians. The authors were historians and anthropologists and emphasized the cultural and social preconditions variables shaping the emergence of caste..

The genetic material at that time did not have the power to detect fine-grained differences (classical autosomal markers) or were only at a single locus (Y, or, more often mtDNA). By the middle to late 2000s there was already suggestion from Y/mtDNA that there was some serious population structure in South Asia, but there wasn’t anything definitive.

A full reading of works such as Castes of Mind leaves the impression that though some aspect of caste (broad varnas) are ancient, much of the elaboration and detail is recent, and probably due to British rationalization. The full title speaks to that reality.

A full reading of works such as Castes of Mind leaves the impression that though some aspect of caste (broad varnas) are ancient, much of the elaboration and detail is recent, and probably due to British rationalization. The full title speaks to that reality.

This is one reason I was surprised by the results from genome-wide analyses of Indian populations when they first came out. On the whole, populations at the top of the caste hierarchy were genetically distant from those at the bottom, and the broad pattern of the differences was mostly consistent across all of South Asia.

To give a concrete example, there are “lower caste” groups in Punjab which may have more steppe pastoralist ancestry than South Indian Brahmins. But within Punjab “highest caste” groups still have more ancestry than “lower caste” groups.

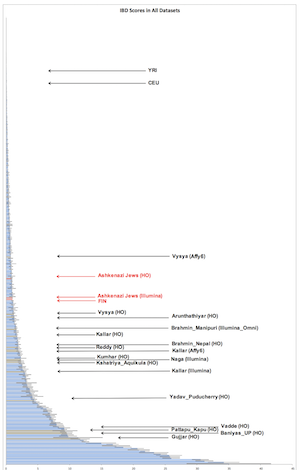

But this wasn’t the most shocking aspect. That was the fact that many castes are genetically quite distant, and anciently so. In a recent paper, The promise of disease gene discovery in South Asia:

We identify 81 unique groups, of which 14 have estimated census sizes of more than a million, that descend from founder events more extreme than those in Ashkenazi Jews and Finns, both of which have high rates of recessive disease due to founder events.

Some of this is due to consanguinity among Muslims and some South Indian groups, but much of it is not. Rather, it’s because genetically it looks like many Indian communities stopped intermarrying ~1,500 years ago. This reduces the effective number of ancestors even in a large population due to increased drift. At a recent conference, an Indian geneticist suggested that this might have something to do with the crystallization of caste Hinduism during the Gupta period. I can’t speak to that, but anyone who has looked at the data sees this pattern.

Some of this is due to consanguinity among Muslims and some South Indian groups, but much of it is not. Rather, it’s because genetically it looks like many Indian communities stopped intermarrying ~1,500 years ago. This reduces the effective number of ancestors even in a large population due to increased drift. At a recent conference, an Indian geneticist suggested that this might have something to do with the crystallization of caste Hinduism during the Gupta period. I can’t speak to that, but anyone who has looked at the data sees this pattern.

To illustrate what I’m talking about, assume ~1% introgression of genes from the surrounding population in a small group. Within 1,500 years 50% of the genes of the target population will have been “replaced.” The genetic patterns you see in many South Asian groups indicates far less than 1% genetic exchange per generation for over 1,000 years in these small groups.

But this post isn’t really about genetics. Rather, I began with the genetics because as an outsider in some sense I’ve never really grokked South Asian communalism on a deep level. Yet the genetics tells us that South Asians are extremely endogamous. It is unlikely that this would hold unless the groups were able to suppress individuality to a great extent. Though people tend to marry/mate with those “like them”, usually the frequency is not 99.99% per generation.

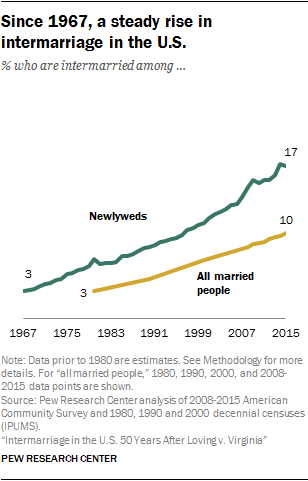

In the United States, things are different. Interracial marriage rates were ~1% in 1960.* This was still during the tail end of Jim Crow in much of the south. Since then the fraction of couples who are in ethno-racial mixed marriages keeps increasing and is almost 20% today. There is still a lot of assortative mating, and ingroup preference. But fractions in the 10-20% range are worrisome for anyone who is concerned about genetic cohesion over a few generations.

In the United States, things are different. Interracial marriage rates were ~1% in 1960.* This was still during the tail end of Jim Crow in much of the south. Since then the fraction of couples who are in ethno-racial mixed marriages keeps increasing and is almost 20% today. There is still a lot of assortative mating, and ingroup preference. But fractions in the 10-20% range are worrisome for anyone who is concerned about genetic cohesion over a few generations.

Though some level of group solidarity exists, explicitly among minorities, and implicitly for non-minorities, individual choice is in the catbird seat today. This was not always so. By the time I was growing up in the 1980s social norms had relaxed, but a black-white couple still warranted some attention and notice. In earlier periods interracial couples had to suffer through much more ostracism from their families and broader society.

In some South Asian contexts, this seems to be true to this day. But unlike the United States the situation is much more complex, with numerous ethno-religious-linguistic subgroups operating in a fractured landscape of power and identity.

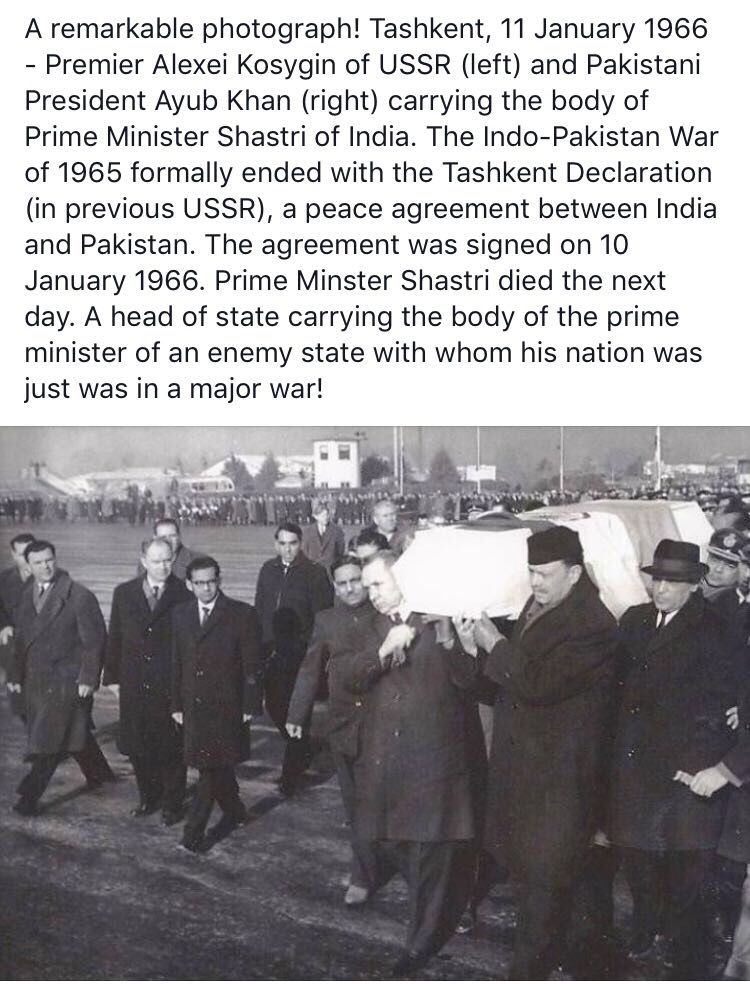

I have wondered in part whether the South Asian fixation on sensitivity and feeling when it came to offense and insult is a function of the strong communal/collective aspect to honor, identity, and decision-making. Muslims outside of South Asia are similar to this, and in the Islamic context the rationale is quite explicit: non-Muslims and heretics are tolerated so long as they don’t challenge the public ethno-cultural supremacy of Islam. For example, atheism is punished less because of deviation from religious orthodoxy and more because it destabilizes public order and is seen as a crime against the state.

The conflicts between Hindus and Muslims in relation to religious parades have their clear analogs to strife between the dominant Catholics and the new Protestant communities in Latin America. But among Hindus the same tendencies crop up in inter-caste conflicts. The sexual brutalization that is sometimes reported of lower caste women by upper castes in parts of the Gangetic plain is a trivial consequence of the power that land-holding upper castes have over all the levers of power over low castes in certain localities. Lower caste men are powerless to defend their women against violation, just as in the American South enslaved black men couldn’t shield their womenfolk from the sexual advances of white men.

Will any of this change? I suspect that economic development and urbanization is the acid that will start to break down these old tendencies and relations in South Asia. It also seems clear that all South Asian communities which are transplanted to the more individualistic West have issues with the fact that collective and communal power is not given any public role, and in a de facto sense has to face the reality that individual choices in mates and cultural orientation are much more viable in the West.

This is particularly important to keep in mind on a blog like this, where many people are reading from South Asia (mostly India) and many are reading in the USA and UK. The conflict of values and signifiers occasionally plays out in these comments! For example, a Hindu nationalist commenter once referred to me as “Secular.” As an atheist, materialist, and someone who is irreligious in terms of identity and affiliation, secular describes me perfectly…in the West. But I was aware of the connotations of the term in India in particular, I told him that in fact, I wasn’t “Secular” in the way he was suggested. The reality is that unlike Indian Americans I don’t take a strong interest in what India does so long as it’s a reasonably stable regime, and so don’t signal my affiliation with Hindu nationalism or anti-Hindu nationalism.

* Latinos were not counted as part of this in 1960, so the rate looking at those numbers is 0.4%. I assume this is an underestimate because of Latinos.