Last week, I shared the first part of my translation of Aasiya, a story from Bilal Hasan Minto’s Urdu short story collection Model Town. Today, I am posting the second part of the story.

Abba and Naveed Bhai were very angry when they heard this story. Because Abba was an advocate of human rights and other similar causes, he said categorically he would report Apa Sughra to the police. Naveed Bhai agreed.

“This is criminal,” Abba had said in English and his use of this admirable language of global importance impressed me very much and drove home the real significance of this incident. Although I was still hesitant to speak English, I had no doubt of its position. Naveed Bhai also spoke it with great fluency. He would often converse even with me in this important language and it is true that I would sometimes respond spontaneously in it.

“She should go to jail,” Naveed Bhai said, putting English to use again.

“Yes. Kot Lakhpat Jail, Lahore,” I concurred straightaway in the same language.

But then Abba himself said we shouldn’t get involved in the matter and also because Apa Sugra was a rude woman, no one should mess with her. They were her daughters; she could do whatever she wanted. We should neither be her friend nor her enemy. We should protect ourselves by staying away from her and only maintain the relationship necessary between neighbors.

“In any civilized country, she would be in jail now,” Abba had said. But Ammi said there was no need for such pointless remarks because we didn’t live in that kind of country. Abba responded that first, what he had said was important and not at all pointless. Second, should one only say things that serve a purpose? If so, why had Ammi looked at one of her rose bushes yesterday and exclaimed what beautiful red roses? She didn’t reply because she normally didn’t consider such remarks from Abba worthy of consideration. This remark — about the civilized country — led to others that were mostly in praise of various other countries of the world. For example, if one traveled westwards, it was certain one would pass through many civilized countries with clean roads, white people, and fast trains, some of which ran underground. Ammi said “When you people praise someone, you make them out to be angels and when you are against them, you portray them as devils. That’s not right.” She said it might be true that such things existed in those countries but people there bathed infrequently, didn’t practice proper hygiene, the women always remained half-naked, and people often got drunk in the evenings. Not just that, they had made places to go in the evenings and drink this lethal liquid. The most unbearable thing was that they cooked food that included the flesh of pigs.

While we were talking over these things, Ismail was serving tea to Ammi and Abba.

“Begum Sahib, there are very tall buildings in England and America — ten- ten stories!”

“Ten-ten stories!” Naveed Bhai mocked him. “Look how surprised he seems, with his eyes popping out. Don’t stay stupid things. Not ten stories, there are even taller buildings there. In America, sixty, seventy, eighty stories are common.”

“Sixty? Seventy?” the teacup trembled in Ismail’s hand.

“And the only reason for that is because they are advanced, civilized people. Something like what Sughra did today couldn’t happen there,” Abba said.

Ismail didn’t quite understand the civilizational differences between the East and the West but he figured that there was something special that enabled trains to run underground and buildings to be built taller than those that existed in our country. And also, that the incident of Apa Sughra and Pari could go some way to explain a few of the differences between East and West.

“No one is saying children shouldn’t be beaten at all. We also beat them, but we don’t nearly kill them,” Ammi said sadly.

Anyway, we said some things like that and fell silent and we didn’t do anything about Apa Sughra’s cruel and disgusting action. But for a while after this incident, whenever Naveed Bhai took Happy out and saw Apa Sughra at the gate, he would say “ush, ush!” hoping that Happy would attack her. But Happy was a quiet, indifferent and tolerant dog. He kept to himself and this irritated Naveed Bhai.

Because Apa Sughra had the base nature I have described, Ammi was startled when Akhtar Auntie mentioned her strange proposal. Ammi tried her best to dissuade her. She asked if Akhtar Auntie knew what she was doing ? For one, those girls, Fari-Pari, were very young, and second, didn’t she know their mother? Akhtar Auntie slapped a hand to her forehead in sorrow and said she was helpless; her son had gone crazy and was insisting he would only marry one of those girls, Fari or Pari, it didn’t matter which, but one of the two.

Ammi asked why? What happened to make Captain Faraz obsessed with Fari-Pari who, if nothing else, must be ten or twelve years younger than him? Akhtar Auntie said a strange madness had taken hold of Faraz. Ever since the prospect of his marriage was mentioned, he had been saying he would marry a very pious woman who observed purdah and looked very pure. She had scolded him, asking if women not observing purdah — like her, his mother — couldn’t be pure? And then the last time he was home he saw Fari-Pari in their burqas returning from school. Since then, he had been pointing out what pious girls lived in our neighborhood, only a house away, walking home along the street across from us. Now there wasn’t any need to go far and he would just marry one of them.

Akhtar Auntie also said she had tried to reason with Faraz, pointing out that the mother of those girls was a witch but it didn’t make any difference to him. On learning of the incident of the stick being impaled in Pari’s head, instead of changing his mind about making this kind of mad woman his mother-in-law, he was even more impressed with how firm and high-principled she must be, and what good morals her daughters must possess. How virtuous they must be. He felt only such girls could truly serve their husbands and fulfill their wifely duties with bowed heads. He also said one could only imagine how girls brought up so well would raise their own children and what examples of excellent character the children would turn out to be.

Abba opined that people had begun to think such weird things under the influence of General Zia’s constant Islamic sloganeering and because Faraz was a soldier, he was even more susceptible. Ammi wasn’t sure if it was right for Abba to make fun of someone’s search for a pure woman. Was Faraz’s desire really to be denigrated?

“You seem to be implying there is something wrong with Faraz wanting to look for a decent girl,” Ammi said.

“Nothing wrong, not at all,” Abba said.

“So then? What’s wrong with him liking Fari-Pari?”

“Ha, ha ha! You’re the real innocent one. Ha ha ha!”

“Oh ho! Don’t make fun of me! Tell us what’s the problem if Faraz says he likes Fari-Pari. What’s wrong with that? Other than their being the daughters of a witch like Sughra.”

“Well, that’s no problem,” Abba said. “Those poor girls should not be punished because their mother is a monster. Actually, they should be given a medal for not saying anything about their mother’s cruelty and bearing her blows as well.So no, that isn’t a problem.”

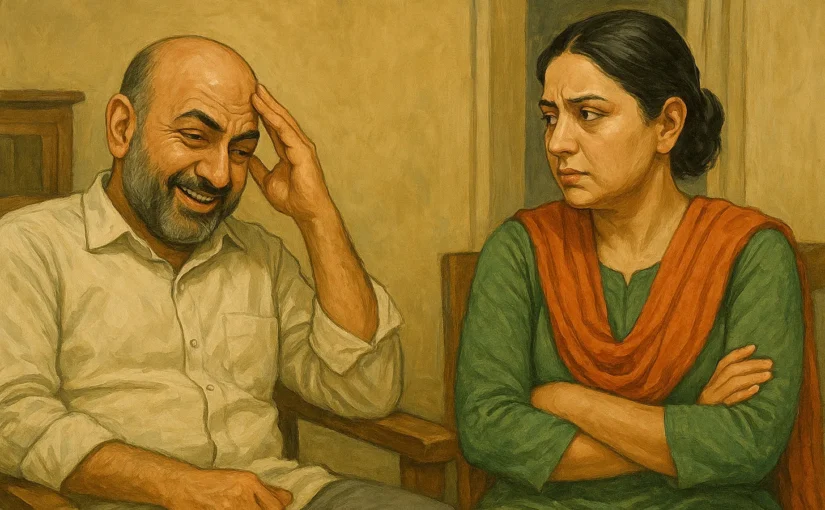

“Then tell us why you are finding fault with Faraz’s choice. Why?” Ammi was now getting upset with Abba for not clearly telling her his point of view. Although he was enjoying this Socratic discourse, not giving her a clear answer and engaging her in considering what the problem might be in Faraz liking Fari-Pari, Ammi’s cup of patience was about to run over.

“First, we should find out what decency and good morals are,” Abba said. “Is it defined anywhere that if a person is this way he is decent and if he is that way then a scoundrel?” Abba tried to move forward with the Socratic dialogue.

“Ok, anyway,” Ammi said in exasperation, “Whatever anyone is, pure or not, I can’t do anything. The problem is that now Akhtar wants me to accompany her to Sughra’s house with Faraz’s proposal, so I’ll have to go.”

“Yes, you are trapped,” Abba said.

“I am badly trapped,” Ammi grumbled. “I will have to go to that witch’s house. Why does Akhtar want to drag me along? It’s not like I’m Sughra’s friend. It just so happens she lives next door. Whenever I see her at the gate, I try to avoid talking to her.”

Ammi’s exasperation was justified. If you need to convey a proposal of marriage, you should go by yourself or take along a relative — an elder, for it is well-known that because they are old and worldly-wise, they should be included in such affairs so they can give good advice and point out important things if others miss them. So you take an elder if you want but why would you ask a neighbor to go with you for a marriage proposal? Just because you’re going to a neighbor’s? But perhaps another reason was that Akhar Auntie was scared of Apa Sughra and she didn’t want to take along a relative, especially an elder, because she didn’t know what might happen at that horrible woman’s place. She didn’t want to be embarrassed in front of her relatives or elders.

“But it seems you will have to go,” Abba said, laughing, as if he found this very amusing. “Akhtar has trapped you.” He added with another laugh. “Now, let’s see what Sughra does to you.”

There was no way out. Ammi owed Akhtar Auntie a favor. This was the same poor Akhtar Auntie who had brought Captain Faraz over to help when General Zia’s military regime had arrested Naveed Bhai for his political activities. Ammi thought if she had to go through this trial, there was no point in delaying, so she called Akhtar Auntie and said they should go the next day. Akhtar Auntie agreed immediately. She was relieved. “Yes, let’s go tomorrow because I just dyed my hair two days ago.”

Ammi suggested she phone Sughra to let her know the two of them would come the next day but Akhtar Auntie said there wasn’t any need. One could visit neighbors without informing them in advance. But Ammi could tell her if she wished. Why should Ammi tell her? The proposal was Akhtar Auntie’s and wasn’t it enough that Ammi was going with her on this distasteful venture. But now it was clear that Akhtar Auntie was afraid of Apa Sughra and wanted to use Ammi as the intermediary. And this despite the fact that there was military rule and she was the mother of an army captain.

Those who are interested can read the final two parts here:

Manto’s stories are always sad

Just to clarify that this story is not by Sadaat Hasan Manto but by Bilal Hasan Minto. Apparently, they are related in some way.

Bilal Hasan Minto’s short story collection “Model Town” is set in Lahore’s Model Town neighborhood in the late 1970s. The narrator is an adolescent boy observing adults around him during the beginning of the Zia era.

Oh yes ok