There emerged a question in the comments below as to what was “brown” or “desi”?

There emerged a question in the comments below as to what was “brown” or “desi”?

Ah, the old demarcation problem! Since there is no “Pope of Brownness” we can all offer our opinions. I take a “liberal” and “broad” view.

There are children adopted from India in the United States who are as physically South Asian as anyone. But often they were raised as English-speaking American Christians. Though many attempt to reconnect with “their culture”, the reality is that their family is the family who adopted them. Their culture is the culture in which they grew into adulthood. But, because of the way they look people make assumptions about them. Perhaps people are racist against them as South Asians.

Despite their involuntary cultural alienation from all things South Asian, I have a difficult time thinking that these kids are not brown. Especially if they so want to identify as such.

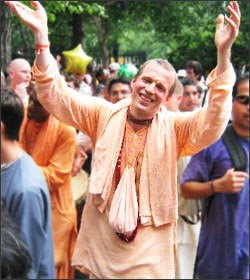

In contrast, you have the case of people of various races who convert to religions with a South Asian provenance or were raised in those religions. Imagine someone whose parents convert to Hinduism, and raise them in India, but they are half Japanese and English American. They don’t “look” Indian. Brown. Or desi. But if they are raised in India, and practice a form of Hinduism, and speak Indian languages, I have a hard time saying that they don’t have a right to “claim” being desi or brown.

There are obviously many other cases. But I wanted to present these two as opposing and inverted instances, as I think they are the boundary conditions of what desi or brown identity is. People can say what they want about themselves. They could be an Iyer raised in Chennai who claims that they’re really not Indian or desi. Or, someone could be a Russian Karelian who is devoutly Orthodox who claims they Indian. I suspect most of us would think that this is nonsense. To be brown or desi does have boundaries.

But we can make the boundaries crisp and tight. Or broad and loose. For example, to assert that to be desi one has to be a believing and practicing Hindu who is racially South Asian would be a narrow definition.

Or, we can make them broad.

As an American, a broad definition works best for me. My children may not speak a South Asian language, worship Hindu gods, or look particularly “Indian.” But of their eight great-grandparents, four of them were born in British India. They have some claim I think to that heritage and identity, if not as strongly as those genuinely encultured.

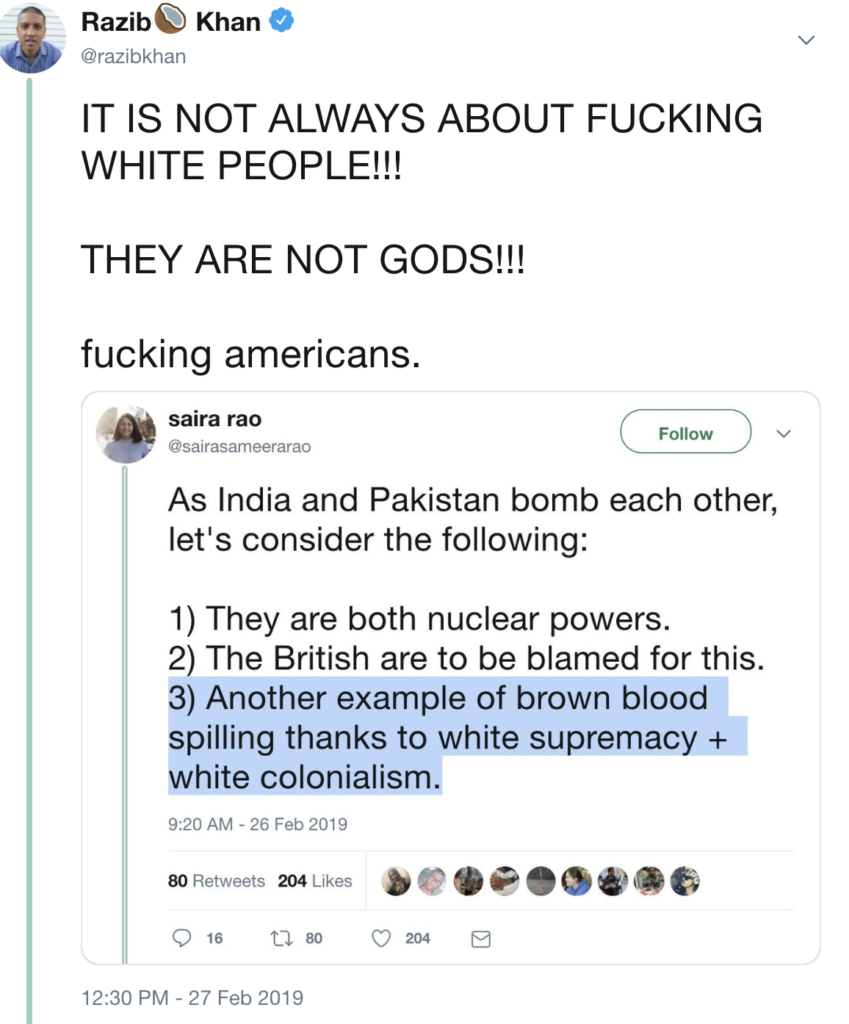

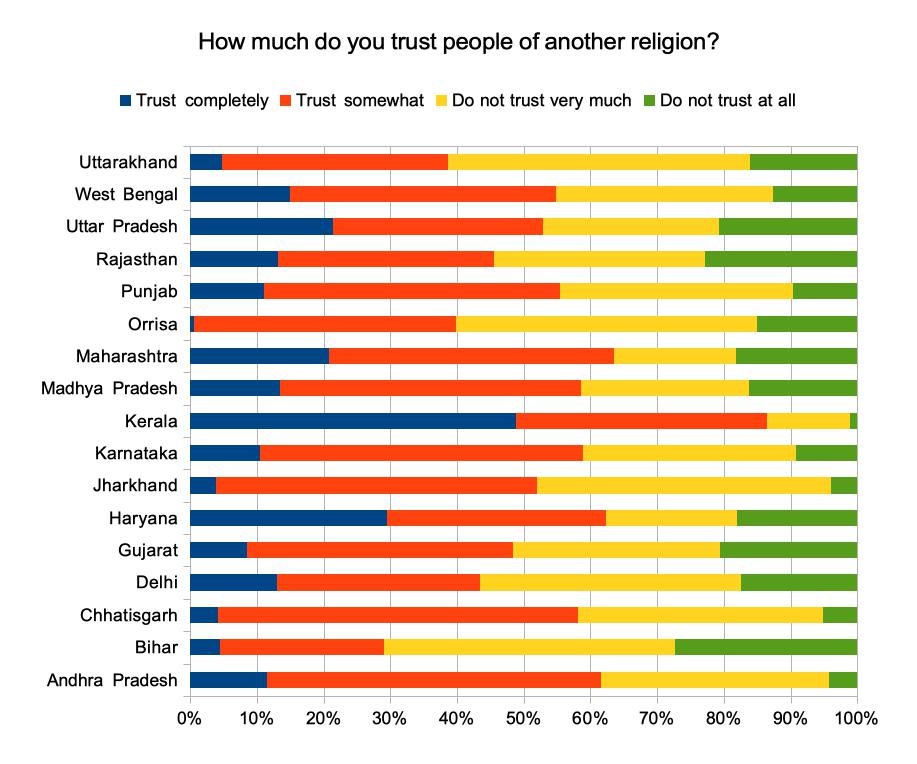

Over at my other weblog, The blood on brown hands is a legacy of all of history. Basically, a long essay where I fire broadsides at reductive postcolonialism in the context of Indian history and communal divisions. The motivation was straightforward: twitter is not really good to outline more subtle or detailed perspectives. But, it is a good platform for people to pepper you with many, many, questions.

Over at my other weblog, The blood on brown hands is a legacy of all of history. Basically, a long essay where I fire broadsides at reductive postcolonialism in the context of Indian history and communal divisions. The motivation was straightforward: twitter is not really good to outline more subtle or detailed perspectives. But, it is a good platform for people to pepper you with many, many, questions.

Another BP Podcast is up. You can listen on

Another BP Podcast is up. You can listen on

There emerged a question in the comments below as to what was “brown” or “desi”?

There emerged a question in the comments below as to what was “brown” or “desi”?