Recently on Twitter someone asked why people of subcontinental backgrounds who leave Islam don’t refamiliarize themselves with the religion of their ancestors. One response could be “well actually, my ancestors weren’t really Hindu…” I think this is a pedantic dodge. In places like Iraqi Kurdistan and Tajikstan some people from Muslim backgrounds are embracing a Zoroastrian identity.

Recently on Twitter someone asked why people of subcontinental backgrounds who leave Islam don’t refamiliarize themselves with the religion of their ancestors. One response could be “well actually, my ancestors weren’t really Hindu…” I think this is a pedantic dodge. In places like Iraqi Kurdistan and Tajikstan some people from Muslim backgrounds are embracing a Zoroastrian identity.

Iraqi Kurds turn to Zoroastrianism as faith, identity entwine:

In a ceremony at an ancient, ruined temple in northern Iraq, Faiza Fuad joined a growing number of Kurds who are leaving Islam to embrace the faith of their ancestors — Zoroastrianism.

Years of violence by the Islamic State jihadist group have left many disillusioned with Islam, while a much longer history of state oppression has pushed some in Iraq’s autonomous Kurdish region to see the millennia-old religion as a way of reasserting their identity.

“After Kurds witnessed the brutality of IS, many started to rethink their faith,” said Asrawan Qadrok, the faith’s top priest in Iraq’s autonomous Kurdish region.

But to be clear, not all the ancestors of the Kurds were Zoroastrian. Some were Christians. Others were probably Jews. The largest numbers on the eve of the Arab conquest were probably a mix of folk mountain pagan, with a patina of Zoroastrianism among the elites. Additionally, modern Mazdaist Zoroastrianism is only a single stream, and one strongly shaped by its Islamic captivity.

And yet on some level, it makes sense that Kurds convert to Zoroastrianism to reconnect with their ancestral Iranian tradition. It is part and parcel of that tradition. Similarly, people of Muslim subcontinental background turning toward Sanata Dharma is not crazy, even if their ancestors were Buddhist or pagans of some sort.

But there’s a problem with “converting” to Hinduism: modern Hinduism is organized around jatis, and being Hindu means being part of the community, and membership in that community is a matter of birth, not choice. Someone who was raised a Muslim and converts to Hinduism can’t just join one of the many local jatis. Of course, there are devotional sects such as ISKON, but these are exceptions, not the rule.

Obviously the same problem occurs in Islam and Christianity. I have read of converts to Islam who were single talk about the difficulty of finding a spouse since they have no “connections” within the community, and being single as a Muslim convert can be very isolating. But, Islam has within it more of an acceptance, like Christianity, that conversion of individuals is possible and even meritorious. Hindus are more ambiguous and ambivalent.

In the premodern world, Hindu communitarianism was a good fit. But in a more individualistic world, it puts Hinduism at some disadvantage.

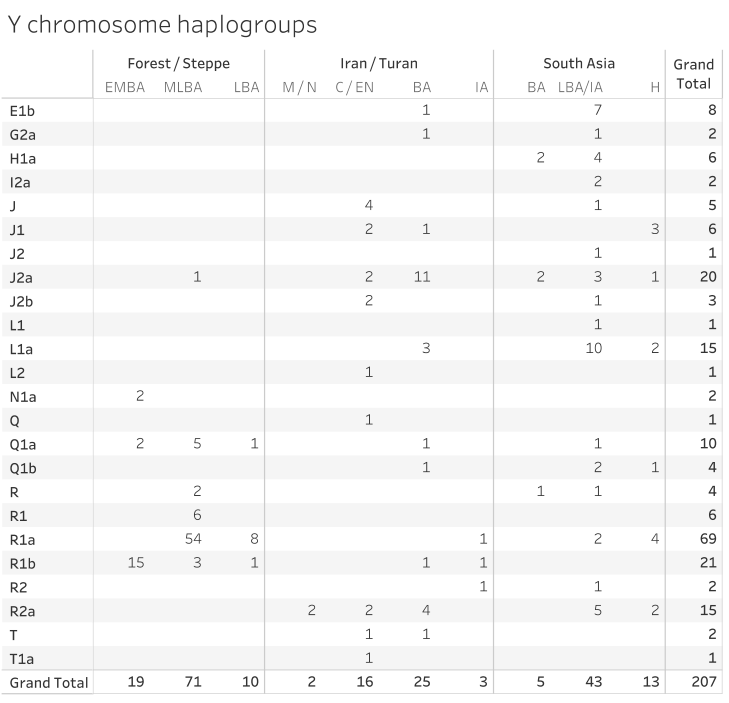

They asked for my opinion. I agree with many of the aspects of the piece. There is something of an attempt, in my opinion, to downplay the coercion and violence that were part of the expansion of many Y chromosomal lineages, groups of males, ~4,000 years ago. In fact, the author of the above piece probably overestimates the fraction of Aryan mtDNA in India; most West Eurasian lineages in South Asia are probably from West Asian, not the Sintashta.

They asked for my opinion. I agree with many of the aspects of the piece. There is something of an attempt, in my opinion, to downplay the coercion and violence that were part of the expansion of many Y chromosomal lineages, groups of males, ~4,000 years ago. In fact, the author of the above piece probably overestimates the fraction of Aryan mtDNA in India; most West Eurasian lineages in South Asia are probably from West Asian, not the Sintashta.

As someone who was raised in the United States as a person of brown complexion, I grew up as an “Indian.” This, despite the fact that the last time any of my ancestors were Indian nationals was before 1947. The main reason is that it is really hard to get people in 1980s America to know what “Bangladesh” was. Yes, there was a famine and a concert in the early 1970s, but this was not very well known. Since I had brown skin, and my parents ate spicy food, it seemed plausible to accept that I was Indian and just “go with it”.*

As someone who was raised in the United States as a person of brown complexion, I grew up as an “Indian.” This, despite the fact that the last time any of my ancestors were Indian nationals was before 1947. The main reason is that it is really hard to get people in 1980s America to know what “Bangladesh” was. Yes, there was a famine and a concert in the early 1970s, but this was not very well known. Since I had brown skin, and my parents ate spicy food, it seemed plausible to accept that I was Indian and just “go with it”.* As a grown adult, with children of mixed background who find my exotic antecedents amusing, I have had to reflect more on the relationship between India and its native religious traditions and identities. Hindus often make the accusation to Indian Muslims and Christians that these religion’s holy sites are elsewhere. In contrast, southern Asia is the locus of “Hindu” spirituality. The sacred geography of Islam in Arabia, the Levant, and for Shia and Sufis more broadly across the Near East (with some expansion in other areas for Sufis, though these are secondary). For Christians, the locus is in the Near East and Europe. But I think this focus on Islam and Christianity takes the eyes off the major prize.

As a grown adult, with children of mixed background who find my exotic antecedents amusing, I have had to reflect more on the relationship between India and its native religious traditions and identities. Hindus often make the accusation to Indian Muslims and Christians that these religion’s holy sites are elsewhere. In contrast, southern Asia is the locus of “Hindu” spirituality. The sacred geography of Islam in Arabia, the Levant, and for Shia and Sufis more broadly across the Near East (with some expansion in other areas for Sufis, though these are secondary). For Christians, the locus is in the Near East and Europe. But I think this focus on Islam and Christianity takes the eyes off the major prize. What does it mean to be Hindu?** I think that it is clear that Hinduism is a precipitation of the indigenous religious traditions of India, a fusion of numerous strands which are quite distinct. As a non-Hindu it is not my role to adjudicate on what is, or isn’t, Hindu, but it seems quite clear that there is something distinct from Islam and Christianity, and that that distinctiveness is usually due to indigenous aspects (some of which were exported through Buddhism out of India). Al-Biruni saw this. Hindus themselves saw this even if they did not think of themselves as a confessional religion.

What does it mean to be Hindu?** I think that it is clear that Hinduism is a precipitation of the indigenous religious traditions of India, a fusion of numerous strands which are quite distinct. As a non-Hindu it is not my role to adjudicate on what is, or isn’t, Hindu, but it seems quite clear that there is something distinct from Islam and Christianity, and that that distinctiveness is usually due to indigenous aspects (some of which were exported through Buddhism out of India). Al-Biruni saw this. Hindus themselves saw this even if they did not think of themselves as a confessional religion. This doesn’t mean that non-Hindu Indians and subcontinentals are not distinctively South Asian. Look at a street scene in Pakistan, and it looks more like New Delhi than Tehran. The people, the color, the foods and density. But for various reasons Pakistanis have rooted their identity in Islam, and this makes identification as subcontinental awkward for many Pakistanis, because Hinduism suffuses subcontinental identity. The word Hindu after all originally just meant Indian.

This doesn’t mean that non-Hindu Indians and subcontinentals are not distinctively South Asian. Look at a street scene in Pakistan, and it looks more like New Delhi than Tehran. The people, the color, the foods and density. But for various reasons Pakistanis have rooted their identity in Islam, and this makes identification as subcontinental awkward for many Pakistanis, because Hinduism suffuses subcontinental identity. The word Hindu after all originally just meant Indian. The point of this post is not to take a particular stance on whether India is or isn’t secular, or should or shouldn’t be secular (whatever that means in India, which is different from the United States). Rather, it’s to acknowledge the “elephant in the room.” Growing up around my parents’ Indian, Pakistani, and Bangladeshi friends, there was always the reality and tension that they had non-subcontinental attachments and identification, in theory. The theory part is made salient by the reality that my parents socialized with Hindu Indians and Bangladeshis (generally Bengali, but not always), but never with Muslims from other regions (the sole exception was when I had an Indonesian best friend, though my parents complained that the Indonesians weren’t very good Muslims anyway so what was the point?). They were foreigners in concrete terms, though there was an abstract brotherhood implied by faith.

The point of this post is not to take a particular stance on whether India is or isn’t secular, or should or shouldn’t be secular (whatever that means in India, which is different from the United States). Rather, it’s to acknowledge the “elephant in the room.” Growing up around my parents’ Indian, Pakistani, and Bangladeshi friends, there was always the reality and tension that they had non-subcontinental attachments and identification, in theory. The theory part is made salient by the reality that my parents socialized with Hindu Indians and Bangladeshis (generally Bengali, but not always), but never with Muslims from other regions (the sole exception was when I had an Indonesian best friend, though my parents complained that the Indonesians weren’t very good Muslims anyway so what was the point?). They were foreigners in concrete terms, though there was an abstract brotherhood implied by faith.

You can also support the podcast as a

You can also support the podcast as a