Google’s plan to talk about caste bias led to ‘division and rancor’:

In April, Thenmozhi Soundararajan, the founder and executive director of Equality Labs — a nonprofit that advocates for Dalits, or members of the lowest-ranked caste — was scheduled to give a talk to Google News employees for Dalit History Month. But Google employees began spreading disinformation, calling her “Hindu-phobic” and “anti-Hindu” in emails to the company’s leaders, documents posted on Google’s intranet and mailing lists with thousands of employees, according to copies of the documents as well as interviews with Soundararajan and current Google employees who spoke on the condition of anonymity because of concerns about retaliation.

Soundararajan appealed directly to Google CEO Sundar Pichai, who comes from an upper-caste family in India, to allow her presentation to go forward. But the talk was canceled, leading some employees to conclude that Google was willfully ignoring caste bias. Tanuja Gupta, a senior manager at Google News who invited Soundararajan to speak, resigned over the incident, according to a copy of her goodbye email posted internally Wednesday and viewed by The Washington Post.

A few points

– This is a big deal in the US right now because a few clueless progressive foundations gave money to Equality Labs. I say clueless because these foundations and granting institutions have zero ability to evaluate the plausibility of systemic caste bias in the US. They probably thought it sounded like a bad thing they should work against, so they funded Equality Labs. Once Equality Labs got its money, it was going to find systemic caste bias, because that’s its raison d’etre.

– The journalists who are reporting that “rising Hindu nationalist movement that has spread from India through the diaspora has arrived inside Google, according to employees” are clueless, and driven along by self-serving sources or their own biases. This particular reporter, Nitasha Tiku is an Ivy League-educated Indian American who has worked in online media (mostly tech journalism) for over a decade. She, like other Indian American reporters, has the right appearance and familial origins to cover a story like “caste in America’s Indian immigrant communities” in the eyes of her editors. But most of these people are not really culturally fluent enough to understand any of the subtleties or nuances of Indian caste, so they fall back on uncritically relaying their source’s talking points, or platitudes and cliches. These people are American, not Indian.

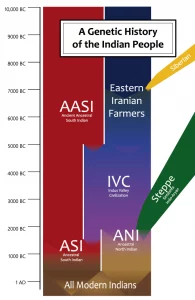

– Obviously, caste and jati are huge issues in the Indian subcontinent, and they are socially relevant institutions that have an impact on your life course. But that is not the case in the US. Indian Americans do come from caste backgrounds, though only 1% come from Dalit family backgrounds (again, it’s weird saying you are a “Dalit American” so almost no Amerians know what a Dalit is). But many Indian Americans raised in the US are very vague about their caste (with exceptions, if you are an Iyer or Mukherjee you pretty much know), and many of them grew up in predominantly non-Indian social environments. The kinship/jati networks that smooth the social functioning of Indian society doesn’t exist in the US. There are partial exceptions with Gujuratis who run family businesses, but these are a minority, and many of the children of successful Gujurati businesspeople in the US still go into professions where their world is mostly not Indian. What is really going with “Diversity, Equity and Inclusion” oriented interrogation of caste in the US is that they want to transpose the black-white model of oppressed and oppressors on a different group so as to organize a “progressive stack rank” of virtue/privilege.

– Though Indian Americans of the 1.5 and 2nd generation are prominent culturally and politically, the vast majority of Indian Americans in the US are immigrants, born and raised in India. Most actually arrived after the year 2000! People like Sundar Pichai or Parag Agrawal are socioculturally quite distinct from Neera Tanden or Kal Pe. Indian American Brahmins and Bainyas who barely have any understanding what this caste identity is may be willing to take on the role of “oppressors” so as to obtain performative self-flaggelation points, but it seems that immigrants, who often struggled to gain a foothold in the American economy and society, are not as eager to engage in this behavior. Especially when they are more aware of the reality of caste and jati in the subcontinent.

– There are nepotistic networks among Indians in tech. I’ve heard multiple people (Indian immigrants) talk about the “Telugu mafia.” But these are not the same as what you would see in India as explicitly related to jati. There are networks connected to schools that everyone went to, or a unicorn that a bunch of early employees cashed out of, etc. It’s the typical thing you see in business in general, where relationships go a long way. But there’s no systemic exclusion of Dalits or lower class people because there are hardly any Dalits in the US, and Indian Amerians are strongly selected for skills, education and higher socioeconomic status in the immigration system. I dislike pointing to prejudice to explain things, but the same sort of dynamics you see in the “Paypal Mafia” when it happens with Indian immigrants seems to be depicted as caste-clannishness by outsiders.

– I am not optimistic that DEI will not include caste in its categories of oppression and marginalization. In 5 years I think it is quite likely that a young white women in HR will be evaluating the caste-jati status of brown-skinned applicants to companies to make sure that the subcontiental employee pool is “diverse.”