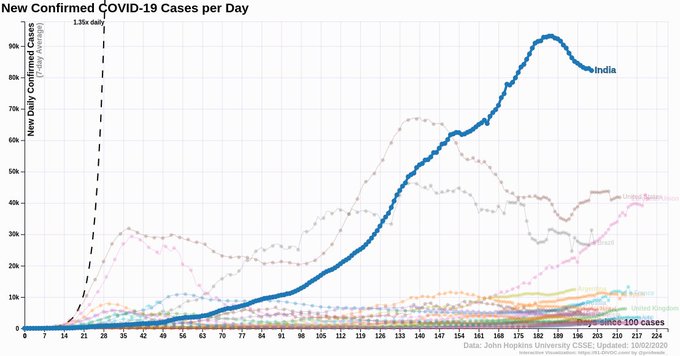

What’s going on in India with COVID-19? Both deaths and cases are now plateauing. Since India is really many nations, this might just be major population centers recovering, even if there are lots of local outbreaks?

Category: Uncategorized

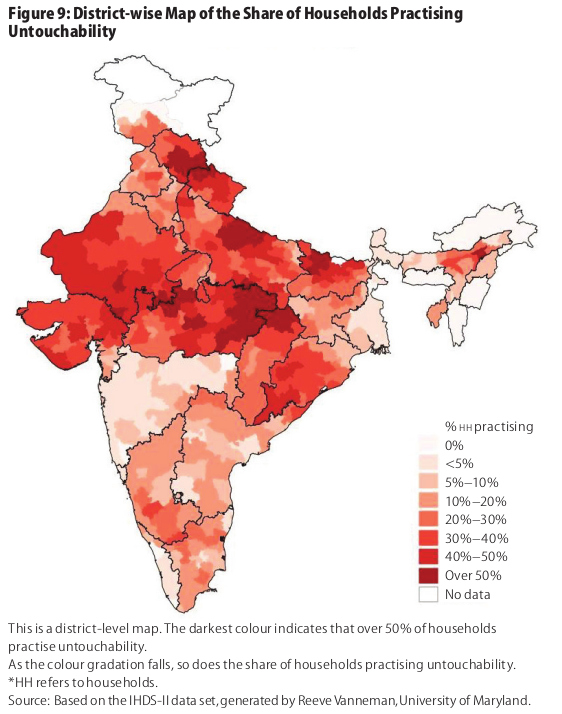

The practice of untouchability by district

I found the above map from Alice Evans. It’s from a paper, The Continuing Practice of Untouchability in India.

The regional patterns turn out to be the most striking. More than education, income, or caste status. You can even see the outline of states, which is indicative of the impact of regional governments on policy and culture.

The Ambition of the Emirates

For a large part of history, the inhabitants of the Arabian peninsula were on the fringe in the rise and fall of empires. They alternated raiding and trading as this wheel of fire rolled on across the dunes. But eventually, the Arabian caravan would be equipped with both sword and word to make haste across the Old World in a relentless raid that would change both history and humanity.

Yet just as quickly as the prized Arabian horses would gallop into newly conquered lands, the Arabs would soon scatter leaving their language, faith, and the prestige of their roots behind in strange lands. Tribalism trumped their newfound unity and the Arabs would once again retreat into their wildernesses and pilgrimages.

That is until wealth erupted from its wastelands. The old elites of the Middle East would now return from their desert exile to begin another round of a game of thrones.

Globalization!

So what is this? What to make of this?

We’re in the 21st century, aren’t we.

Some tidbits on the state of United States in 1800

The United States today is the 3rd most populous country on earth with 330MM people. We all know that the first European settlements in North America began circa 1600. But what did the eastern seaboard look like, some 200 years later in 1800 – a good twenty four years after the Declaration of Independence?

To understand America some 200 years ago, one of the best books to read is Henry Adams’s History of the Administrations of Jefferson and Madison. The period covered is from 1800 to 1816. But let’s focus on Chapter 1 of the work – that discusses the physical state of US in 1800.

In 1800 the whole of United States (i.e. the 13 states, and not the whole continent) had 5.3 MM persons. To put that in perspective, the US in 1800 when Jefferson took office had fewer people than the city of Bangalore today. The figure of 5.3MM is relative to the 15MM who lived in the much much smaller British Isles the same year, and the 27MM people in the French Republic post revolution. Out of 5.3MM, about a fifth were African slaves. So the free white population was about 4.5MM. This excludes the native American population (on whose population I can’t readily find estimates in the book or elsewhere).

Nearly all of this 5 MM was concentrated along the Atlantic seaboard and the 13 original states. Barely about 0.5MM lived beyond the Alleghany mountains of Pennsylvania and had made their way to territories westward like Ohio and Kentucky.

Travel was mostly through land for getting to the interior regions even on the eastern seaboard. And land travel as one would expect was pretty expensive and very very long.

Let’s take the cities of New York and Boston – separated by some 220 miles – a distance covered in about 4 hours by car today. Back in 1800, the Boston to New York journey was a 3 day affair, despite the existence of a “tolerable highway” in Adams’s words. There were apparently stage-coaches from NY that departed to Boston thrice a week carrying passengers and mail. So it’s not just about the 3 day long journey but also the infrequency of travel options. Just thrice a week.

Let’s take NY to Philadelphia – two towns separated by 100 miles (and a 2 hour cab drive today). Back in 1800, the stage-coach ride from NY to Philadelphia took the “greater part of two days” in Adams’s own words. The journey between Baltimore and Washington DC (the country’s capital then as now) was a perilous one in 1800 – as there were forests to traverse. These two towns are barely an hour’s drive from each other today.

Let’s see what Adams has to say about housing in 1800 US –

“Fifty or a hundred miles inland more than half the houses were log-cabins, which might or might not enjoy the luxury of a glass window. Throughout the South and West houses showed little attempt at luxury; but even in New England the ordinary farmhouse was hardly so well built, so spacious, or so warm as that of a well-to-do contemporary of Charlemagne.”

Back in 1800, it used to take 16 days for a mail to reach Lexington Kentucky from Philadelphia – two towns separated by 650 miles. A mail from Philadelphia to Nashville took 22 days.

How large were the great cities of US in 1800 –

- Philadelphia – 70,000 people

- New York – 60,000

- Boston – 25,000

So Philadelphia was no larger than a midsized town like Liverpool (also 70K) in England. London to put things in perspective had 1 million inhabitants in 1800.

For those familiar with NYC, here’s an interesting tidbit from Adams on how the city was back in 1800 – “the Battery was a fashionable walk, Broadway a country drive, and Wall Street an uptown residence”!!

So this was the state of US, a good 200 years after the European first settled it! That’s a long long time. Even after 200 years, two third of the American population was within 50 miles of the Atlantic seaboard!

Adams’s take on the state of US presided over by Jefferson is very sobering. It tells us how difficult “progress” is, and how much of a long haul just about everything was all over the world, before the railroad and the steam engine (particularly in the absence of waterways).

Also this chapter underscores the sheer physical challenge posed by the American continent – a far greater challenge than say Western Europe where the sea is within a couple of hundred miles of most parts.

It also helps explain why North America was so uninhabitable and backward for millennia despite being colonized by man as early as 15,000BC. Even the highly civilized Eurasian man could barely bring himself to move away from the seaboard after spending 200 years on the continent.

The author tweets @shrikanth_krish

On Indians in East Africa

The Indian diaspora is said to be over 30 million. While the popular tendency is usually to talk of the diaspora in the West (which is recent in formation), Indians have played a far more important role in East Africa if we take a long historical view of the past 150 years

Thomas Sowell’s very fine book “Migrations and Cultures” is an eye-opener in this respect as it sheds a great deal of light on the Indian engagement in Africa since the middle of 19th century. This short post dwells briefly on the Indian contributions in East Africa (particularly Uganda / Tanzania / Kenya) drawn mainly from Sowell’s work.

Let’s take the Tanzanian island outpost of Zanzibar off the African east coast. While the Indian presence in Zanzibar today is not much to write home about, this island was one of the first African territories to be settled by Indians. There was a phase in history when Zanzibar was practically run by Indians. In 1860, a report mentioned – “All the shopkeepers and artisans at Zanzibar are natives of India”!

The numbers of Indians in Zanzibar weren’t great. Only about 5000 in the 1860s. But nearly all foreign trade was conducted by them. As of 1872, an American trader owed Indian financiers in the Island $2MM and a French firm owed these financiers at least $4MM.

While in mid 19th century, Indian presence was largely in Zanzibar and some coastal areas of East Africa, the interior was opened up when the British constructed the great railroad that connected Mombasa port in Kenya to Lake Victoria in Uganda in late 19th century. 16000 laborers were involved in the construction of this great pioneer Railway project. Of which 15000 were Indians.

What’s interesting is that these coolies were pretty expensive compared to the indigenous African labor. Yet the expensive indentured Indian labor from thousands of miles away was preferred as they were more valuable and productive than locally available African labor. The railroad construction proved the trigger for much of the Indian migration to the African mainland – particularly Kenya and Uganda. Much of the migration was from Gujarat.

The Indian settlements in these parts were a momentous event in Africa’s long history. In Sowell’s words, the Indian shops in East Africa were the first commercial retail establishments ever encountered by these African villages in their entire history. The Indians in East Africa were the first to import / sell cereal. Sowell credits them for “transforming East Africa from a subsistence and barter economy into a money economy” in the late 19th / early 20th century.

As an example Taxes in Uganda until late 19th century were paid in kind. Starting in 20th century they were paid in money and the currency was rupees!

In 1905, a report in Kenya declared – “80% of the present capital and business energy in the country is Indian”. In 1948, Indians owned over 90% of all cotton gins in Uganda. In the 1960s, when the Indian population peaked in Uganda, their share of the population was about 1%. But as per some estimates the “Asian” contribution (mostly Indian) to the national GDP ranged from 35% to 50%.

In 1952, there were twice as many African traders as Indian traders in Uganda, but the Indian traders did 3 times as much business as the Africans! Despite Govt regulations which hampered Indians from setting up shops (again as per Sowell).

Resentment against Indian dominance eventually got a lease of life when most of the East African countries became independent in the 60s and 70s. The dictator Idi Amin’s expulsion of most Ugandan Indians in the early 70s was a notorious episode at the time when the Asian population in Uganda dropped from 96K in 1968 to ~1000 in 1972.

The case in Kenya was not very different from Uganda. Indians dominated the Kenyan economy. Yet post Kenyan Independence, the pressures to “africanize” meant that the Asian (mostly Indian) numbers in Kenya dropped from 176K in 1962 to 25K in 1975.

Today Indians play a more marginal role in the region than they once did. .While we tend to diss imperialism a lot, we sometimes forget that imperialism was also a driver of such unlikely inter-continental migrations which brought commercial culture to hitherto unexplored regions.

Political independence to the region did not work out very well for the enterprising Indian diaspora. The Indian businessman who had played a large role in building these economies was driven out of it, with little gratitude.

The story of Indians in East Africa is a much unheralded one, that ought to be celebrated more in India, and must be taught in Indian textbooks. This was not a political colonization driven by kings. This was a mission undertaken by hard working ordinary Indians who shone with their probity, enterprise and sweat.

All the more reason to celebrate and commemorate it.

The author tweets @shrikanth_krish

Open Thread – 9/26/2020 – Brown Pundits

I have mixed feelings about casting Dev Patel as Gawain. Though my feelings are not strong, they are similar to my feelings about casting white actors as non-Europeans in the past: you get over it, but it takes away from verisimilitude.

Please make sure that you subscribe to the podcast (there are links to various platforms on the main website at the link). We don’t always post show-notes due to being busy.

Brahmanism Versus Brahminism

Yes – read the title twice.

Was inspired to write this due to Gaurav’s interesting post on Brahmanical Patriarchy. Note – I am a non-Brahmin Hindu.

I’ve always been pretty aware of the difference between Brahman – a word for the metaphysical supreme Godhead/substance in Hinduism and brāhmin – the priestly caste in the varna system. But many times, I see people using the 2 interchangeably as if they are one and the same. Ditto for Brahmanism and Brahminism.

Now if you’ve followed my writing, you know I’m pretty critical of academic takes on Hinduism and academia in general. I generally think both Brahmanism and Brahminism are frankly bullshit IYI terms coined by outsiders and unfortunately adopted widely nowadays.

However, Gaurav’s take on “Brahmanism” (all Hindu practices & rituals which have a basis in scriptures like the Vedic Canon, Puranas/Itihasa, Sutras/Shastras as Brahmanism) is a fair description to me of core Vedic or Hindu thought. A Hinduism rooted to the Upanishadic Brahman that contrasts (but more or less doesn’t clash with) many local or Agamic traditions. A tradition that really does bind the diversity of Hinduism together by common roots and cause. I’d prefer to call it Vedic Dharma or Vedic religion (because I don’t like the Brahman/brahmin casual mixing) but that’s beyond the point.

Onto Brahminism – now this is a term I loathe. To my knowledge, this term was coined by Jesuit missionaries visiting India to convert heathens to the one true faith. These days, the term is honestly just a cover for Brahmin bashing and even more so Hinduism bashing. Brahminism = Brahmanism = standard and core Hindu faith and customs. Basically, the shtick is, all of Hinduism is for and by Brahmins and is solely used as a tool for oppression. If that core description of Vedic (or according to them – Brāhmin) thought and ritual is scrapped away, the link of diverse Hindu traditions is gone and an ideological balkanization occurs. This is a very pretty picture if you’re in opposition to Hinduism. See the monstrosity that is Dravidianism for an example today.

A casual scroll through social media will have people criticizing innocent/non-harmful Hindu rituals and customs such as doing puja for a puppy or vegetarianism and label them as “Brahminical/Brāhmin OPPRESSION!” Yet many of these practices have nothing to do with Brāhmins in this day and age or even in the past (depending on time and geography of course).

While I agree that ending caste discrimination should be a paramount cause of Hindu sampradays and Hinduism in the present, the “Brāhmin Boogeyman” is increasingly just a cover for criticizing Hinduism as a whole and removing agency/tradition/history from non-Brahmin Hindus.

On language diversity in India – North vs South

Language remains a bone of contention within Indian discourse, and much of it surrounds the North Indian insistence on Hindi (more specifically Khariboli, the high prestige dialect of Hindi spoken traditionally in the region around Delhi) versus the Southern insistence on lingual diversity and the immense pride in regional lingual traditions (be it Tamil, Kannada or Telugu)

But the fundamental divide is this –

Lingual diversity in North India is significantly lower than in the Deccan, which creates fundamental differences in the attitudes towards lingua franca like Khariboli

Roughly 450 million people from Bikaner to Jamshedpur speak similar tongues Yet the 60 million people in Karnataka can barely follow the 70 million people in TN

The reason Khariboli in my view established itself as the primary lingua franca of the North Indian plain is because the differences across the various languages spoken from Panipat to Gaya were not as massive to start with. Clearly smaller than the differences between say Telugu and Tamil.

But why is that? One obvious proximate reason –

South had regional polities unlike North where Empires spanned the whole Indo-Gangetic plain, driving greater homogeneity in the spoken Prakrits.

But what are the underlying reasons for the greater political unity of North India?

-

- The Northern terrain is more uniform, unlike South which is a plateau. Also the nature of the terrain varies a lot down south. E.g. Tamil Nadu is clearly a plain, while neighboring Kerala is hill country and Karnataka is an elevated plateau. This perhaps limited social intercourse of people in ancient times.

-

- In the North we have the great Ganges river. The Ganga-Jamuna river system unites the land, linking the whole expanse of land through maritime commerce. South has no such single river system but separate provincial rivers like Krishna, Godavari in AP, Kaveri in Karnataka and TN.

-

- North India was setted earlier by the Indo-Aryans. Its proto-historical period can be conservatively dated to 1500-1000 BCE. In contrast, Southern India emerges out of pre-history much later towards the beginning of the Common era. The earlier settlement meant that the Gangetic plain is significantly denser and also uniformly dense. E.g. UP’s density is over 800 per sq. km, while Bihar is at 1100. Whereas in the South, there is greater variation in population density. Tamil Nadu is at 550 per sq.km, Kerala is 800+, while Karnataka and Andhra are significantly less dense (around 300).. The higher and more uniform density up north perhaps contributed to a more homogeneous lingual culture.

But the last hypothesis is unsatisfactory. It leaves us with the question – Why didn’t the less dense and more isolated parts of North India (Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh evolve distinct regional cultures? Having said that, it must be noted that the relatively denser parts of these two states – Malwa and Mewar are culturally closer to the Gangetic mainstream culture than other parts of these provinces where we do see greater variation in dialect (E.g. Marwar)

I feel the vastly different levels of lingual diversity between the Northern plains and Deccan impact how the discourse is conducted today on the issue of Hindi and Khariboli.

The “typical” North Indian argument underrates the diversity down south. And hence goes like this –

Hey. We are Braj, Avadhi, Bhojpuri speakers. We don’t mind our differences, and have chosen to embrace Khariboli as the “standard” tongue. Why can’t you southerners do so as well?

The “typical” South Indian argument overstates the lingual diversity up north.

Hey..why are you guys adopting Khariboli without resistance. Why have you guys given up on Braj, Avadhi, Bhojpuri? Get a spine!

Both sides in my view get it wrong. Northerners understate lingual diversity down south. Southerners overstate lingual diversity up north. This is at the root of most culture wars around language

The author tweets @shrikanth_krish

Dammed it you dont: The hydraulic origins of the divergence between the Raj, India and Pakistan

Historians have put forth the the idea that complex political states originated as ‘hydraulic empires’, a need for ancient societies to manage vast water systems. Governments have evolved from their ancient origins to do a lot more beyond managing water. However, we shall see in this post that attitudes towards water can lead to important differences in the evolution of spatially and temporally adjacent political entities.

In terms of hydrology and geology, there are striking contrasts between the Indo-Gangetic plain and peninsular India. The Indo-Gangetic plain is drained by perennial rivers, fed by both Himalayan glaciers and monsoonal precipitation. Peninsular India, on the other hand, is drained only by monsoon-fed seasonal rivers. Geologically, the Indo-Gangetic plain is blessed with alluvial soil which is both fertile and holds groundwater. Peninsular India is composed of harder rocks, which leads to more runoff and less groundwater retention. Water has always been a much harder challenge in peninsular India than the Gangetic plain.

The British Raj and its successor state of India, had vastly different attitudes towards the hydro problems of peninsular India. However, the Raj’s successor state of Pakistan never had to deal with the water challenges of peninsular India. Pakistan remained agriculturally more productive per worker than India till 2017. India had to construct 5264 medium and large dams (compared to Pakistan’s 150) to overtake Pakistan on that count. A side effect was an advanced industrial and technical base.

We first discuss the dam policy of the British Raj, which is known for its investments in railways and canals. A striking rarity in the Raj’s impressive portfolio of grand infrastructure projects are mega dams. It is not that the British did not build significant water-works in India, but these were overwhelmingly barrages and canal irrigation projects. And the absence of large dams was not due to a lack of technical expertise, indeed, elsewhere in the empire, (notably Canada and Australia), British engineers pioneered the techniques that underlie the construction of modern, large scale dams.

So what explains the Raj’s dam reluctance in their richest canvas ? It is likely that the politics of British India underlies the inhibition towards dams. The centre of gravity of the British Indian empire was the Indo-Gangetic plain. It was the most populated region, the region which produced the most recruits for the British Indian army and the region they really needed to manage. And this region did not need dams. The large dams the British built were mainly in deep South India, the largest dam there was a project conceived by the king of Mysore, Krishnaraja Wodeyar.

The modern day Republic of India found itself in a very different political situation. The elites of peninsular India were organized and had the numbers to match their Gangetic counterparts. Prime minister Nehru, although Gangetic, was deeply influenced by the economic philosophy of the Soviet Union. At the time, the Soviet Union was a master of building mega dams. A massive dam building project ensued, all across India. In the Gangetic plain, this meant increased agricultural yields, but in peninsular India, the dams were a game-changer. Vast tracts of land in Madhya Pradesh were brought under productive cultivation. Interior Maharastra developed a sugarcane belt. Gujarat has become a leader in cotton, tobacco and groundnuts.

Equally important, dams made large cities viable outside the Gangetic plain. Dams and their reservoirs are the only reason the nascent urban centres of peninsular India (Mumbai, Pune, Ahmedabad, Bengaluru and Hyderabad) could become the dynamic mega-cities they are today. In contrast, Gangetic plain cities continue to get their water from the perennial rivers that they are set on (Delhi-Yamuna, Lucknow-Gomti, Patna-Ganges, Kolkata-Hooghly and so on).

It is conceivable that the extreme importance of large dams and water management structures pushed India’s post-independent elites to invest heavily into engineering education. The public and private enterprises in charge of dam construction, irrigation boards, and hydroelectric machinery provided employment for the labour produced by these elite institutes. These projects thus serviced the needs and aspirations of both urban elites and the vast rural voting masses.

On the other hand, Pakistan’s situation was quite different. With the exception of Islamabad, Pakistan’s cities get their water in the same way Gangetic Indian cities do, surface water and ground water. Developing state-of-the-art water management technology was never an imperative for the Pakistani elite.