Congratulations (Sriram, Ansun, Gokul, Ashwin)

Indian-Americans Sriram Hathwar of New York and Ansun Sujoe (top) of Texas

shared the title after a riveting final-round duel in which they nearly

exhausted the 25 designated championship words. After they spelled a

dozen words correctly in a row, they both were named champions.

The past eight winners and 13 of the past 17 have been of Indian

descent, a run that began in 1999 after Nupur Lala’s victory, which was

later featured in the documentary “Spellbound.”

Earlier,

14-year-old Sriram opened the door to an upset by 13-year-old Ansun

after he misspelled “corpsbruder,” a close comrade. But Ansun was unable

to take the title because he got “antegropelos,” which means waterproof

leggings, wrong.

Sriram entered the final round as the

favorite after finishing in third place last year. Ansun just missed the

semifinals last year.

They become the fourth co-champions in the bee’s 89-year history and the first since 1962.

“The competition was against the dictionary, not against each other,”

Sriram said after both were showered with confetti onstage. “I’m happy

to share this trophy with him.”

Sriram backed up his status as

the favorite by rarely looking flustered on stage, nodding confidently

as he outlasted 10 other spellers to set up the one-on-one duel with

Ansun. The younger boy was more nervous and demonstrative, no more so

than on the word that gave him a share of the title: “feuilleton” the

features section of a European newspaper or magazine.

“Ah,

whatever!” Ansun said before beginning to spell the word as the stage

lights turned red, signaling that he had 30 seconds left.

Although they hoisted a single trophy together onstage, each will get

one to take home, and each gets the champion’s haul of more than $33,000

in cash and prizes.

Gokul Venkatachalam of Missouri finished third, and Ashwin Veeramani of Ohio, was fourth.

The Hin-Jew conspiracy begins to take shape

To update the Two Nation Theory: their maximum villain-enemies are our maximum hero-friends and vice versa.

……

To his Israeli partners, Modi’s profile

as an opponent of Muslim extremism—a perceived common enemy,

particularly in the wake of the 2008 terrorist attacks in Mumbai—only

made him more appealing.

Surveys

by the Israeli Foreign Ministry have found that Indian support for

Israel is higher than in any other country polled, beating out even the

United States. “Rural Indians see Israel as an agricultural superpower,”

said Shimon Mercer-Wood, Southeast Asia desk officer at the Israeli

Foreign Ministry. “Urban India sees Israel as a leader of innovation and

entrepreneurship.”

……….

It is actually high time that Israel and India take the partnership to the next level in the civilian domain (military links are already strong).

Technology wise India needs Israel..desperately. But (as we imagine) a country with one billion friends is what Israel needs India far more, in particular in the coming days as the Boycotts, Divestment and Sanctions campaign picks up steam in the West.

In the near future, it may well be that the European doors will close. Anti-semitism is right now rampant and deadly across the continent and is likely to accelerate as the Left-Islam alliance grows in strength. In the mean-time India under the Hindu Brotherhood will be shining brightly (welcome sign: swastika?)

At the same time we wish Palestine and Kashmir to remain peaceful (it will never be resolved because their sacred ground is ours as well).

It is beyond pathetic (but understandable) that people cannot see beyond their artificial communities…..all of them .

……..

Israelis who have met Narendra Modi, India’s newly elected prime

minister-designate, gush about him and what he means for Israel. At a

recent event at the Institute for National Security Studies, in Tel

Aviv, he was described in glowing terms: “outgoing”; “assertive”;

“extremely, extremely clever”; and “very tachles, very direct,

very Israeli.”

Among the calls Modi received congratulating him on his

win last week was one from Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu,

who told

his cabinet at their weekly meeting that Modi had replied by expressing

the desire to “deepen and develop economic ties with the state of

Israel.”

….When Modi, the head of the Hindu nationalist BJP party, is sworn in

as prime minister on Monday, he will become the only Indian premier to

have ever visited the Jewish state. He has close relationships with

Israeli business leaders, and his landslide victory has left many

anticipating the possibility of a great leap forward in Indian-Israeli

relations—and with it, a billion new customers and allies.

Israel’s relationship with India has long been a quiet affair, with a

lot going on behind the scenes, but not much happening in public.

Though India voted to recognize Israel in 1950, successive governments

in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s avoided public ties with Jerusalem,

partly to appease India’s large Muslim minority and partly out of a

desire to avoid alienating Arab allies. India didn’t establish official

relations with Israel until 1992, making it the last non-Arab,

non-Muslim country in the world to do so.

Despite this, commercial ties, technology sharing, space exploration,

and military cooperation between the two countries have all grown

vigorously in recent years. Bilateral trade has shot up from less than

$200 million in 1992 to almost $4.4 billion in 2013 (not including

weapons sales, which account for billions more). The growth in bilateral

trade has been driven largely by precious stones and by defense

spending. The exception is in Gujarat, the state where Narendra Modi has

served as chief minister for the past 13 years.

In Gujarat, Israeli industry was not only welcomed by Modi but actively pursued. Huge tenders for a semiconductor plant , a new port , and a desalination plant

were awarded to Israeli bidders. Israeli agriculture, pharmaceutical,

alternative energy, and information technology companies have flourished

there. This isn’t incidental: Modi’s campaign was based on replicating

his economic success in Gujarat on a national scale, and much of that

success was tied up with Israel.

In Gujarat, Modi emphasized privatization and small government. He

opened financial and technological parks, brought in foreign investment,

and cracked down on corruption. Under his administration, the state’s

economy expanded by more than 10 percent annually. In 2010, in Modi’s third term in office, Forbes named Gujarat’s largest city, Ahmedabad, as the third-fastest growing city in the world.

Modi’s career was nearly derailed in 2002 when riots broke out in

Ahmedabad; an estimated 1,000 Muslims were killed by Hindu radicals

during the violence. Modi’s government was accused of not doing enough

to stop the massacre, and while Modi was cleared of any wrongdoing by

the Indian Supreme Court’s Special Investigation Team in 2009, he was banned

from visiting the United States over his role in the violence—a

circumstance that drove Modi to develop relationships with other foreign

partners, particularly Israel and Japan, instead.

In 2006, Modi accepted an invitation to visit Israel for an

agricultural technology conference. The five-day trip sparked an ongoing

relationship; Modi began encouraging partnerships with Israeli

ministries and advised his constituents to study Israeli agricultural

and water-management systems.

To his Israeli partners, Modi’s profile

as an opponent of Muslim extremism—a perceived common enemy,

particularly in the wake of the 2008 terrorist attacks in Mumbai—only

made him more appealing.

Modi’s BJP has often been supportive of Israel. Though diplomatic

relations between New Delhi and Jerusalem were first officially

established under the dominant Congress Party in 1992, it was during the

last BJP coalition government, between 1999 and 2004, that the

relationship blossomed. India’s Foreign Minister Jaswant Singh, of the

BJP Party, visited Israel in 2000, and in 2003 Ariel Sharon became the

first Israeli leader to visit India.

According to a report in the International Business Times,

Modi has suggested that he may make the first official state visit by a

sitting prime minister to Israel during his term of office. His timing

is impeccable: The Indian public seems especially well primed for a

closer alliance with Israel as well.

Surveys

by the Israeli Foreign Ministry have found that Indian support for

Israel is higher than in any other country polled, beating out even the

United States. “Rural Indians see Israel as an agricultural superpower,”

said Shimon Mercer-Wood, Southeast Asia desk officer at the Israeli

Foreign Ministry. “Urban India sees Israel as a leader of innovation and

entrepreneurship.”

…

In the last few months a string of cooperative anti-terror agreements

was signed between the two countries; negotiations over a Free Trade

Agreement are ongoing. One of the largest Indian business delegations

ever to visit Israel will be attending the MIXiii conference in Tel Aviv this month. But Modi’s victory has the potential to send these efforts into overdrive.

….

“Modi likes Israeli Chutzpah,” said a senior member of the AgileTree

investment company who has dealt personally with him in Gujarat for

years and asked to remain anonymous because of continuing business

operations with both major parties. “If only a fraction of what happened

in Gujarat will happen in India as a whole, the state of Israel will be

one of the biggest beneficiaries.”

……

Link: http://www.tabletmag.com/jewish-news-and-politics/173767/modi-israels-new-best-friend

….

regards

29 May 1953 (on top of the world)

I

banged out a brief message on my typewriter for a Sherpa to take down to

the Indian radio station first thing next morning. SNOWCON DITION BAD . . .

ABANDONED ADVANCE BASE . . . AWAITING IMPROVEMENT. It meant, as the

Indian radiomen would not know, …that Everest had been

climbed on May 29 by Hillary and Ten-zing.

There is one parochial

grievance (a familiar one). The Western (UK) Press really needs to make

more of a decent effort to give credit to the “”natives” and not grasp

it all for Queen and Country. How many people know that it was

Rakhaldas Bandopadhyay who discovered Mohen-jo-Daro and also Jagadish

Chandra Bose who invented the radio (not Marconi- it took IEEE-

Institution of Electrical and Electronics Engineers – about 100 years to

correct the record)? Similarly it was Radhanath Sikdar, (described in Wiki as an Indian mathematician and surveyor from Bengal), was the first to identify Everest as the world’s highest peak in 1852 (Sir George Everest was the Surveyor General of India, who preceded Andrew Waugh- the man who officially made the announcement).

Finally, in March 1856 he announced his

findings in a letter to his deputy in Calcutta.

Kangchenjunga was declared to be 28,156 ft (8,582 m), while Peak XV was

given the height of 29,002 ft (8,840 m). Waugh concluded that Peak XV

was “most probably the highest in the world”.

Peak XV (measured in feet) was calculated to be exactly 29,000 ft

(8,839.2 m) high, but was publicly declared to be 29,002 ft (8,839.8 m)

in order to avoid the impression that an exact height of 29,000 feet

(8,839.2 m) was nothing more than a rounded estimate. Waugh is therefore wittily credited with being “the first person to put two feet on top of Mount Everest”.

A few more micro-details. Sir Edmund Hilary (20 July 1919 – 11 January 2008) is obviously the inspiration for Captain Keith Mallory, the hero of the Guns of Navarone authored by Alistair MacLean. His mate Tenzing Norgay (late May 1914 – 9 May 1986), was born Namgyal Wangdi, in Tengboche, Khumbu in the foot-hills of Everest. He was a Nepalese Buddhist [ref. Wiki]

…….

Not

many modern adventures, at least of the physical, peaceable kind, ever

achieve the status of allegory. One was, of course, that

ultimate feat of exploration, that giant step for all mankind, the

arrival of Apollo 11 upon the moon. The other was the first ascent of Mount Everest.

It was allegorical in many senses.

The mountain stood on one of the earth’s frontiers, where the Himalayan

range separates the Tibetan plateau from the vast Indian plains below.

The adventure was symbolically a last earthly adventure, before

humanity’s explorers went off into space. The expedition that first

climbed Everest was British, and a final flourish of the British Empire,

which had for so long been the world’s paramount power. And as it

happened, the news of its success reached London, the capital of that

empire, on the very morning a new British queen, Elizabeth II, was being

crowned in Westminster Abbey. Almost everything meant more than it had a

right to mean, on Everest in 1953.

It did not always seem so at the

time. When those two men came down from the mountaintop, all one of them

said was: “Well, we’ve knocked the bastard off.”

The mountain was bang on the line

between Tibet and Nepal, two of the world’s most shuttered states, but

during the 19th century the British, then the rulers of India, had

regarded them as more or less buffer states of their own empire, and had

seldom encouraged exploration.

….

Everest had first been identified and

measured from a distance, when a surveyor working far away in Dehra Dun,

in the Indian foothills, had realized it to be the highest of all

mountains, and in 1856 it had been named after Sir George Everest,

former surveyor general of British India. It was known to be holy to the

people living around it, it looked celestial from afar, and so it became

an object of tantalizing mystery, an ultimate geographical presence.

Nobody tried to climb it—certainly

not the Sherpa people who lived at its foot—until 1921, when a first

British expedition was allowed to have a go. Between the two world wars

five other British attempts were made. All went to Everest via Tibet,

attacking the northern side of the mountain, but after World War II,

Tibet was closed to foreigners, and for the first time climbers

approached the mountain from the south, in Nepal. By then the British

Raj had abdicated, and in 1952 a Swiss expedition was the first to make a

full-scale attempt from the Nepali side. It failed (but only just). So

there arose, in the following year, a last chance for the British, as

their empire lost its vigor, its power and its purpose, to be the first

on top.

The empire was fading not in

despair, but in regret and impoverishment. The British no longer wished

to rule the world, but they were understandably sad to see their

national glory diminished. They hoped that by one means or another their

influence among the nations might survive—by the “special relationship”

with the United States, by the genial but somewhat flaccid device of

the Commonwealth, or simply by means of the prestige they had

accumulated in war as in peace during their generations of supremacy.

revived fortunes upon his daughter, the future Queen Elizabeth II, who

would accede to the throne in June of the following year. All was not

lost! It might be the start, trumpeted the tabloids, of a New

Elizabethan Age to restore the dashing splendors of Drake, Raleigh and

the legendary British sea dogs.

With this fancy at least in the

backs of their minds, the elders of the Royal Geographical Society (RGS)

in London, who had organized all the previous British expeditions to

Everest, made their plans for a final grand-slam assault upon the

mountain. The British had long thought that if it was not exactly their

right to be the first on the top of the world, it was in a way their

duty. Everest wasn’t in the British Empire, but it had been within a

British sphere of influence, as the imperialists liked to say, and so

they considered it a quasi-imperial peak. As early as 1905, Lord Curzon,

the inimitably imperial viceroy of India, had declared it “a reproach”

that the British had made no attempt to reach that summit of summits;

nearly half a century later the British public at large would have been

ashamed if some damned foreigners had beaten them to it.

So it was an emblematically powerful

expedition that the RGS sponsored this time. It had a strong military

element—most of its climbers had served in the armed forces. Most had

been to one of the well-known English private schools; several were at

Oxford or Cambridge. Two were citizens of that most loyally British of

the British dominions, New Zealand. One was from Nepal, and therefore

seemed a sort of honorary Briton.

Himalayan experience, and professionally they included a doctor, a

physicist, a physiologist, a photographer, a beekeeper, an oil company

executive, a brain surgeon, an agricultural statistician and a

schoolmaster-poet—a poetic presence was essential to the traditional

ethos of British mountain climbing. Astalwart and practiced company of

Sherpa mountain porters, many of them veterans of previous British

climbing parties, was recruited in Nepal. The expedition was, in short,

an imperial paradigm in itself, and to complete it a reporter from the

LondonTimes, in those days almost the official organ of

Britishness in its loftiest measures, was invited to join the expedition

and chronicle its progress.

The leader of this neo-imperial

enterprise was Col. John Hunt, King’s Royal Rifle Corps, a distinguished

mountaineer, one of Montgomery’s staff officers in World War II, and an

old India hand. The reporter from The Times was me.

Three men, in the end, came to

dominate the exploit. Hunt himself was the very incarnation of a leader,

wiry, grizzled, often wry and utterly dedicated. Whatever he was asked

to do, it seemed to me, he would do it with earnest and unquenchable

zeal, and more than anyone else he saw this particular task as something

much grander than a sporting event. As something of a visionary, even a

mystic, he saw it as expressing a yearning for higher values, nobler

summits altogether. He might have agreed with an earlier patron of

Everest expeditions, Francis Younghusband of the RGS, who considered

them pilgrimages—“towards utter holiness, towards the most complete

truth.” Certainly when Hunt came to write a book about the adventure, he

declined to talk about a conquest of the mountain, and simply called it

The Ascent of Everest.

The second of the triumvirate was

Tenzing Norgay, the charismatic leader of the Sherpas with the

expedition, and a famously formidable climber—he had climbed high on the

northern flank of Everest in 1938, on the southern flank in 1952, and

knew the mountain as well as anyone. Tenzing could not at that time read

or write, but his personality was wonderfully polished. As elegant of

manner as of bearing, there was something princely to him. He had never

set foot in Europe or America then, but in London later that year I was

not at all surprised to hear a worldly man-about-town, eyeing Tenzing

across a banquet table, say how good it was to see that “Mr. Tenzing

knew a decent claret when he had one.” When the time came for Hunt to

select the final assault parties, the pairs of climbers who would make

or break the expedition, he chose Sherpa Tenzing for one of them partly,

I am sure, for postimperial political reasons, but chiefly because he

was, as anyone could see, the right man for the job.

His companion to the summit was one

of the New Zealanders, emphasizing that this was a British expedition in

the most pragmatic sense—for in those days New Zealanders, like

Australians and even most Canadians, thought themselves as British as

the islanders themselves. Edmund Hillary the beekeeper was a big, burly,

merry, down-to-earth fellow who had learned to climb in his own New

Zealand Alps but had climbed in Europe and in the Himalayas too. He was

an obvious winner—not reserved and analytical like Hunt, not

aristocratically balanced like Tenzing, but your proper good-humored,

impeturbable colonial boy. There was nobody, I used to think, that I

would rather have on my side in the battle of life, let alone on a climb

up a mountain.

The expedition went like clockwork.

It was rather like a military campaign. Hunt took few chances in his

organization, and tested everything first. He’d brought two kinds of

oxygen equipment to the mountain, for instance, and climbers tried them

both. Camps established on the mountain flanks enabled men to haul

equipment up in stages, and when they were sick or overtired during

those three months on the mountain, they went down to the valleys to

rest. Two pairs of climbers made final assaults. The first team, Thomas

Bourdillon and Charles Evans, turned back 285 feet from the top. It was

late in the day, and the exhausted climbers saw the final approach as

too risky. Nobody was killed or injured on the 1953 British Everest

Expedition.

Everest was not the most difficult

mountain in the world. Many were technically harder to climb. Once more

it was a matter of allegory that made its ascent so wonderful an event.

It was as though down all the years some ectoplasmic barrier had

surrounded its peak, and piercing it had released an indefinable glory.

It was Ed Hillary the New Zealander who said they’d knocked the bastard

off, but he meant it in no irreverent sense—more in affectionate

respect. For myself, cogitating these mysteries in the course of the

expedition, and gazing at the spiraling plume of snow that habitually

blew like a talisman from Everest’s summit, agnostic though I was I did

begin to fancy some supernatural presence up there. It was not the most

beautiful of mountains—several of its neighbors were shapelier—but

whether in the fact or simply in the mind, it did seem obscurely nobler

than any of them.

Everest 1953, I fear, did much to

corrupt all this. Nationalists squabbled with a vengeance for the honors

of success on the mountain, and Tenzing in particular was the subject

of their rivalries. He was Asian, was he not, so what right had the

imperialists to call it a British expedition? Why was it always Hillary

and Tenzing, never Tenzing and Hillary? Which of them got to the top

first, anyway? All this came as a shock to the climbers, and even more

to me. When it came to such matters I was the most amateurish of them

all, and it had never occurred to me to ask whether Hillary the

Antipodean or Tenzing the Asian had been the first to step upon that

summit.

I was not, however, an amateur at my

trade. Just as the physiologist had been busy all those months

recording people’s metabolisms, and the poet had been writing lyrics,

and the cameraman had been taking pictures, so I had been active sending

dispatches home to The Times. They went via a cable station in

Kathmandu, the capital of Nepal. There was no road to Kathmandu from the

mountain. We had no long-distance radio transmitters, and certainly no

satellite telephones, so they went by the hands of Sherpa

runners—perhaps the very last time news dispatches were transmitted by

runner.

It was 180 miles from the mountain

to the capital, and the faster my men ran it, the more I paid them. The

journey was very hard. The best of them did it in five days—36 miles a

day in the heat of summer, including the crossing of three mountain

ranges more than 9,000 feet high. They very nearly broke the bank.

I kept a steady stream of dispatches

going, and I was not at all surprised to find that they were often

intercepted by rival papers and news organizations. I did not much care,

because they generally dealt more in description or surmise than in

hard fact, and were couched anyway in a fancy prose that no tabloid

would touch; but I did worry about the security of the final,

all-important message, the one that would report (or so we hoped) that

the mountain had actually been climbed. This I would most decidedly

prefer to get home without interference.

Fortunately, I had discovered that

some 30 miles from our base camp, at the foot of the mountain, the

Indian Army, keeping a watch on traffic out of Tibet, had established a

radio post in touch with Kathmandu. I arranged with its soldiers that

they would, if the need arose, send for me a brief message reporting

some important stage in the adventure. I resolved to keep this resource

in reserve for my final message. I could not, however, afford to let the

Indians know what such a message contained—it would be a secret hard to

keep, and they were only human—so I planned to present it to them in a

simple code that appeared not to be in code at all. A key to this

deceitful cipher I had sent home to The Times.

The time to use it came at the end

of May, and with it my own chance to contribute to the meanings of

Everest, 1953. On May 30 I had climbed up to Camp 4, at 22,000 feet in

the snow-ravine of the Western Cwm, a valley at the head of a glacier

that spills out of the mountain in a horrible morass of iceblocks and

crevasses called the Khumbu Icefall. Most of the expedition was

assembled there, and we were awaiting the return of Hillary and Tenzing

from their assault upon the summit. Nobody knew whether they had made it

or not.

As we waited chatting in the snowy

sunshine outside the tents, conversation turned to the forthcoming

coronation of the young queen, to happen on June 2—three days’ time; and

when Hillary and Tenzing strode down the Cwm, and gave us the thrilling

news of their success, I realized that my own moment of allegory had

arrived. If I could rush down the mountain that same afternoon, and get a

message to the Indian radio station, good God, with any luck my news

might get to London in time to coincide with that grand moment of

national hope, the coronation—the image of the dying empire, as it were,

merging romantically into the image of a New Elizabethan Age!

And so it happened. I did rush down

the mountain to base camp, at 18,000 feet, where my Sherpa runners were

waiting. I was tired already, having climbed up to the Cwm only that

morning, but Mike Westmacott (the agricultural statistician) volunteered

to come with me, and down we went into the gathering dusk—through that

ghastly icefall, with me slithering about all over the place, losing my

ice ax, slipping out of my crampons, repeatedly falling over and banging

my big toe so hard on an immovable ice block that from that day to this

its toenail has come off every five years.

It was perfectly dark when we

reached our tents, but before we collapsed into our sleeping bags I

banged out a brief message on my typewriter for a Sherpa to take down to

the Indian radio station first thing next morning. It was in my

skulldug code, and this is what it said: SNOWCON DITION BAD . . .

ABANDONED ADVANCE BASE . . . AWAITING IMPROVEMENT.

It meant, as the

Indian radiomen would not know, nor anyone else who might intercept the

message on its tortuous way back to London, that Everest had been

climbed on May 29 by Hillary and Ten-zing. I read it over a dozen times,

to save myself from humiliation, and decided in view of the

circumstances to add a final two words that were not in code: ALLWELL, I

wrote, and went to bed.

It went off at the crack of dawn,

and when my runner was disappearing down the glacier with it I packed up

my things, assembled my little team of Sherpas and left the mountain

myself. I had no idea if the Indians had got my message, had accepted it

at face value and sent it off to Kathmandu. There was nothing I could

do, except to hasten back to Kathmandu myself before any rivals learned

of the expedition’s success and beat me with my own story.

But two nights later I slept beside a

river somewhere in the foothills, and in the morning I switched on my

radio receiver to hear the news from the BBC in London. It was the very

day of the coronation, but the bulletin began with the news that Everest

had been climbed. The queen had been told on the eve of her crowning.

The crowds waiting in the streets for her procession to pass had cheered

and clapped to hear it. And the news had been sent, said that

delightful man on the radio, in an exclusive dispatch to The Times of London.

ascent’s big anniversary? Not at the queen’s London gala. Hint: For

decades he has aided the Sherpas.

they have it just right. Yes, he has had lucrative endorsement gigs

with Sears, Rolex and now Toyota (and has led expeditions to the South

Pole and the source of the Ganges).

mostly devoted himself to the Sherpas, a Tibetan word for the roughly

120,000 indigenous people of mountainous eastern Nepal and Sikkim,

India, since he and Tenzing Norgay, the most famous Sherpa of all,

summated Mount Everest 50 years ago. “I’ve reveled in great adventures,”

Sir Edmund, 83, says from his home in Auckland, New Zealand, “but the

projects with my friends in the Himalayas have been the most worthwhile,

the ones I’ll always remember.”

Hillary and the Himalayan Trust,

which he founded in 1961, have helped the Sherpas build 26 schools, two

hospitals, a dozen clinics, as well as water systems and bridges. He

also helped Nepal establish SagarmathaNational Park to protect the very

wilderness that his ascent has turned into the ultimate trekking and

climbing destination, attracting 30,000 people a year.

His love of the area is tinged with

sadness. In 1975, Hillary’s wife and youngest daughter were killed in a

plane crash while flying to one of the hospitals. “The only way I could

really have any ease of mind,” he now recalls, “was to go ahead with the

projects that I’d been doing with them.” (A grown son and daughter

survive; he remarried in 1989.)

History’s most acclaimed living

mountaineer grew up in rural New Zealand too “weedy,” he says, for

sports. But heavy labor in the family beekeeping business after high

school bulked him up for his new passion—climbing. Impressive ascents in

New Zealand and the Himalayas earned him a spot on the 1953 Everest

expedition. Hillary was knighted in 1953, and he graces New Zealand’s $5

note and the stamps of several nations. Yet he works hard to debunk his

heroic image. “I’m just an average bloke,” he says, albeit with “a lot

of determination.”

It’s of a piece with Hillary’s

modesty that he would rather talk about his partner Tenzing, a former

yak herder who died 17 years ago. “At first he could not read or write,

but he dictated several books and became a world ambassador for his

people.” What Hillary admires about the Sherpas, he adds, is their

“hardiness, cheerfulness and freedom from our civilized curse of

self-pity.”

To hear him tell it, climbers are

ruining Everest. Since 1953, 10,000 have attempted ascents: nearly 2,000

have succeeded and nearly 200 have died. Hillary concedes that Nepal, a

very poor country, benefits from the permit fees—$70,000 per

expedition—that climbers pay the government. Still, he has lobbied

officials to limit the traffic. “There are far too many expeditions,” he

says. “The mountain is covered with 60 to 70 aluminum ladders,

thousands of feet of fixed rope and footprints virtually all the way

up.”

Hillary plans to celebrate the

golden anniversary of the first ascent in Kathmandu, he says, with “the

most warmhearted people I know.”

…….

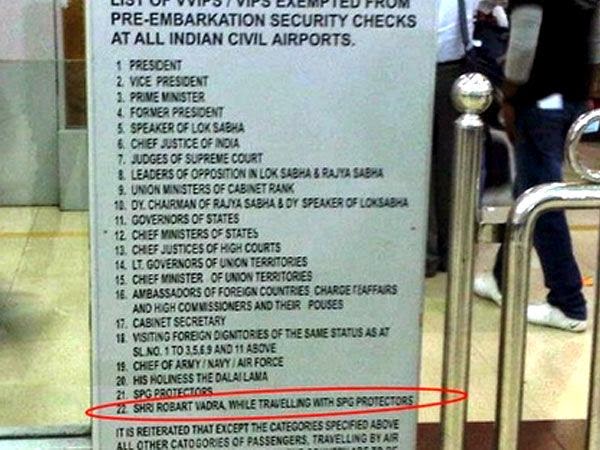

The banana republic strikes back

RV is famous for having said that he was a mango man in a banana

republic. Now that he is truly an Aam Admi, he should be also thoroughly

investigated for his sources of wealth. Let the witch hunt begin (we use the word advisedly). (For those who are not familiar with Hindi, we observe an teacher who is fed up with a troublesome student. Asked about his ambition in life, the student replies: I want to be a son-in-law)

Also there is a lot of push-back from Congress and elsewhere about the (educational) qualifications of the cabinet ministers. Here is one comparison the sycophant army may want to think about (Ashok Khemka has been the main man behind the effort to unearth corruption linked to Robert Vadra and his associates, he has been harshly treated just for doing his job):

……

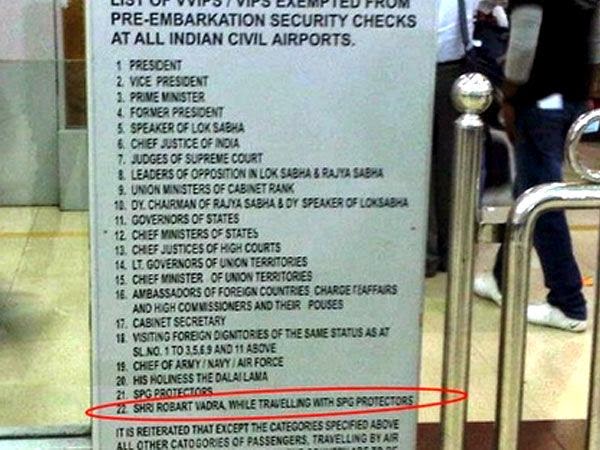

With the Gandhi family out of power, son-in-law Robert Vadra may lose his exalted exempt-from-frisking-at-airports status.

After taking over as aviation minister of Friday, Ashok Gajapathi Raju

Pusapati said that “security should be meaningful not ornamental” in

reference to Vadra who is the only individual named in the list of

dignitaries exempt from security checks at airports. All others on that

list are high constitutional positions with Vadra being the only

individual.

“It is for the home ministry to see the threat

perception of individuals. But generally, by and large, Indians should

go through security checks,” Raju said.

The Bureau of Civil

Aviation Security has 30 positions on the exempt list which begins with

the President of India and goes upto special protection group

protectees. The only individual listed in that list (on number 31) is

Robert Vadra, Sonia Gandhi’s son-in-law.

Last week, the Air

Passengers’ Association of India had written to aviation secretary Ashok

Lavasa why was Vadra getting this special privilege that is reserved

for Constitutional authorities only. The list of exempt people is

displayed prominently at all airports and the inclusion of Vadra’s name

in it led to many people writing to the Association, asking it to take

up the matter with the government.

regards

Left must exit, stage left (says “real India”)

One may say that this is the key difference between India and Pakistan, where the Leftists could not get a strong enough foot-hold (there was a stronger faction in the East – Bangladesh – which faced the fury of the Army in 1971).

Strangely enough the Left also stopped the Far Left in its tracks. In the 1960-1970s when Bengal was being torn apart by violence, the Left fought off the Naxalites in collaboration with the infamous Siddhartha Shankar Ray of the Congress. (Ray would be later deputed to troubled Punjab and he teamed up with KPS Singh Gill to stop the Khalistani movement in its tracks).

Even more strange was the action of the CPI (Communist Party of India, not to be confused with its evil twin, the CPIM) during the dark days of the Emergency. The Communists aligned with Mrs Gandhi, supposedly with the backing of Moscow.

Hartosh Singh Bal (in a write-up before the election results was announced) looks at the reason(s) why the Left has essentially faded from the Indian scene, when it was dominant even a decade ago (and occupied the principal king-maker role in the area of coalitions, even to the extent of co-supporting govts with the aid of the BJP).

………………….

Left, but by the time of her 6 March interview with Arnab Goswami on Times Now,

the third front that the Left parties had been working assiduously to cobble

together since June 2013 had already displayed enough evidence of falling apart

without any help from her.

While the seat-sharing agreement with Jayalalithaa’s

All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam had come apart at the last minute, Naveen

Patnaik’s Biju Janata Dal in Orissa had paid no heed to the possibility of an

alliance, and Nitish Kumar’s Janata Dal (United) in Bihar had agreed to a

tie-up only with the Communist Party of India, snubbing the principal Left

party, the Communist Party of India (Marxist).

CPI(M), the CPI, the All India Forward Bloc and the Revolutionary Socialist

Party—to partner with these regional leaders was made even more humiliating by

the fact that many of them had supported the BJP in the past.

Jayalalithaa, in

particular, shares a strong rapport with the party’s prime ministerial

candidate, Narendra Modi. Given that the regional parties could end up

supporting the BJP again after the election, the Left was in effect willing to

run the risk that its votes could eventually shore up Modi.

climbdown, most regional figures had come to the conclusion that, for the

present, what mattered was maximising their share of seats in parliament, and

that there was no need to oblige the Left, which is no longer in a position to

exert the kind of influence it once did in any alliance that involved the

Congress.

Under these circumstances, soon after Mamata chose to tell Goswami

that she was willing to support Jayalalithaa as prime minister, Jayalalithaa

reciprocated with a phone call, opening up the possibility that if the

post-election scenario permits, a fourth front without the Left may have more

chances of taking shape than the third front being shaped by the Left.

gets—worse, even, than 2009, when the third front it had espoused alongside

Mayawati had been marginalised. In contrast, in 2004, the Left parties had

stitched together a series of tactical alliances that not only ensured the unexpected

defeat of the Vajpayee-led NDA, but also made them key players in the

subsequent UPA-I government.

While a Marxist would undoubtedly claim that the

contrasting scenarios were but the product of a difference in material

conditions (if Mamata Banerjee can be so termed) it is difficult to avoid

examining the role of the respective individuals guiding the Left under these

different circumstances—Harkishan Singh Surjeet and Prakash Karat.

together a workable alliance owed much to Surjeet, the then general secretary

of the CPI(M). One of the few communist leaders of significance from north of

the Vindhyas, Surjeet also had a personal rapport with almost every important

political leader outside the Hindu Right. The two failures, however, took place

under the guidance of Prakash Karat, a Marxist theoretician with little

experience of electoral politics, who does not even enjoy the goodwill of all

his colleagues within the CPI(M) politburo.

shortly after his death in 2008, his protégé Sitaram Yechury, who has always

harboured ambitions of becoming the party’s general secretary, chose to end a

piece, titled with some deliberation as ‘Comrade Surjeet—the True Marxist,’

thus:

At

the Deoli concentration camp in the 1930s, Surjeet was there along with other

legendary Communist figures like B.T. Ranadive, Dr G. Adhikari and P.C. Joshi.

To keep themselves amused, they would take bets with each other. Surjeet

boasted that he could consume a ser of ghee—a thought, which the others baulked

at—the ghee was somehow smuggled in and Surjeet consumed it in one go, only to

have the other three stay awake sitting by his side the whole night fearing

that he would now meet his end.

Surjeet

woke up in the morning, and with his lota went into the khet (field) and

returned to tell his comrades, that “urban Communists will have to work very

hard to understand real India”—a lesson that remains relevant even today.

seem, words are weighed with great care within the CPI(M). Yechury may have

included himself among the urban communists, but it was not lost on anyone

within the party who the actual target of this veiled barb was.

successor has considerable merit. The handover of power in the CPI(M) from

Surjeet to Karat in 2005 was not just a transfer of power across generations,

but also across attitudes. Karat enjoyed the support of the vast mass of the

cadre in the CPI(M), a party that has always emphasised adherence to Marxist

doctrine. But as subsequent events have shown, this doctrinaire approach is out

of step with the requirements of electoral politics, which had shaped Surjeet’s

vision.

the party in directions not amenable to its own cadre because he was among the

nine “navratanas” of the CPI(M), who formed the party’s politburo after

a split from the CPI in 1964. His entry into active politics dated back to

1930, when he joined Bhagat Singh’s Naujawan Bharat Sabha—which even then

required that its members not have anything to do with communal bodies, or

parties which disseminated communal ideas—and took part in the independence

movement. He subsequently fought and won two elections for the Punjab Assembly.

the formation of coalitions and alliances, Surjeet had the stature of an elder

statesman both within the party and outside it. His worldview had been shaped

by the partition of Punjab, and he abhorred communal politics—whether of a

minority, such as the kind preached by the radical Sikh leader Bhindranwale, or

of a majority, as espoused by the BJP. In national politics, as far as he was

concerned, keeping the BJP out of power was the Left’s main objective.

theoretician, a student of the Marxist academic Victor Kiernan in Edinburgh. He

returned to India in 1970 to join the party, where he became closely associated

with another “navaratna,” the then general secretary of the party P

Sundaraiyya, who resigned from his post in 1975 because of the CPI(M)’s

“revisionist” tendencies. Sundaraiyya was forced to go underground after the

CPI(M) split from the CPI in 1964, and then again in 1975 after the imposition

of the Emergency.

Delhi unit in the early 1970s, Karat participated in student politics while

studying at Jawaharlal Nehru University, before being elected to the CPI(M)’s

Central Committee in 1985, and then to its politburo in 1992. These roles

confined him to working within the party, and he was mostly uninvolved with the

larger politics of the country till he took over from Surjeet in 2005.

inherited Sundaraiyya’s view that the party needed to maintain an equidistance

from the BJP and the Congress. This view had led him, in 1996, into marshalling

the party’s young guard to block Jyoti Basu’s ascension to prime ministership

when a coalition government came to power with outside support from the

Congress. First HD Deve Gowda and then IK Gujral took over as prime minister

for brief periods, before the BJP came to power in 1997.

UPA-I that allows us to see what was lost in 1995 from the Left’s point of

view. In 2004, with Surjeet still in charge, while the CPI(M) and, to a lesser

extent, the CPI were considerably strengthened by strong showings in their home

turfs of West Bengal and Kerala, they also made a number of tactical alliances

with regional parties such as the DMK in Tamil Nadu, which added to their tally

of seats. The influence of the resulting Left Front on the UPA government was

visible in a number of ways, including the passing of the legislation that

resulted in the NREGA.

heed to the practical necessities of politics after he took over as general

secretary of the CPI(M) in 2005. By the time the Left’s alliance with the

Congress broke down in 2008, over the Indo–American nuclear deal, personal

relations between Karat and the UPA leadership had deteriorated to the extent

that their only communication was taking place through newspaper interviews—a

situation that would have been inconceivable when Surjeet was in charge.

Equally inconceivable would have been the fact that the Left was eventually

marginalised because Mulayam Singh Yadav came to the rescue of UPA-I, something

he would have never done if Surjeet was in command, given their personal

relationship.

the alliance as a setback. For the 2009 elections the Left managed to stitch

together another alliance, which included Mayawati. This alliance seemed

certain of being an influential factor in any government that would be formed,

but the Left had not taken into account Mamata Banerjee’s Trinamool Congress.

Her party won 19 seats and, in alliance with the Congress, was able to oust the

CPI(M) from West Bengal in the ensuing assembly polls in 2011.

leave Karat with no say in UPA-II, it also saddled him with fresh problems

within the party. Faced with economic challenges within the state, the Bengal

unit of the CPI(M), under Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee, had in the mid 2000s already

adopted an industrial policy that was far more pro-market than had ever been

envisaged before by the party.

which hail largely from Kerala, blamed those policies for the defeat, the

Bengal unit took the line that the doctrinaire stand over the nuclear deal had

pushed the Congress into an alliance with Mamata, which eventually led to the

Left’s defeat in the state. Unlike Surjeet, Karat was seen as an interested

party in this war, given his support within the Kerala unit. As a result of

this internal strife, the CPI(M) increasingly resembles two regional parties

with very different economic visions, held together by a central authority that

is getting weaker.

electoral tally of the Left parties, which together won 24 seats in 2009, the

CPI(M) and the CPI had sought state-specific alliances with several regional

parties. All of these alliances have come undone. In Tamil Nadu the Left asked

the AIADMK for two seats each for the CPI(M) and the CPI, a comedown from the

three each offered to them by the DMK in 2004. But given that there was little

the Left was bringing to the table, Jayalalithaa, much like Naveen Patnaik in

Orissa and Nitish Kumar in Bihar, seems to have calculated that the best

strategy for each party in the forthcoming elections is to fight for seats

independently and await the poll results, which could throw up any number of

possibilities.

on its own, the Left faces another unexpected challenge. In past elections, it

regularly picked up a number of isolated seats outside Kerala and West Bengal

through the very sort of tactical alliances that have now fallen through. In

these other states, the rise of the AAP provides an alternative choice for many

voters who desire a liberal, left-of-centre option. Unclear though the AAP’s

stance is on so many issues of concern to such voters, the party at least

brings with it new hope and the prospect of change.

the CPI(M) expect that a debacle in the forthcoming polls, which seems

increasingly likely now, will pave the way for the party to elect a new general

secretary at its next congress, due in 2015. But the end of Karat’s term does

not mean his hold over the party will come to an end—in all likelihood his

successor will be someone who meets with his approval.

weakened, the conditions that brought Karat to the fore still exist, given that

the Kerala unit still wields more support within the organisation than the West

Bengal unit. In some ways the very strength of doctrine that keeps the

organisation together is largely responsible for its decreasing electoral

relevance. As a result, if the party chooses another urban, doctrinaire leader

in the mould of Karat to be its next general secretary, as seems likely, there

will be no one happier than the BJP, which would then have truly put the ghost

of comrade Surjeet—and others like him who understood the “real India”—behind

it.

‘Aaj jaane ki zid na karo’

Farida

Khanum is one of the last of the Ghazal greats. She grew up in

Kolkata and has great fondness for the city. The denizens of this city

are known for their musical taste, and they have (naturally) great love for Farida. A

beautiful love story that is reaching its end as the giants exit the stage one by one.

Literary Meet. I met Banerjee—“Mala”—at last year’s KaLaM, and told her I was

making a documentary film about Farida Khanum.

Our conversation took place one

night in a car; we were weaving past rotten old buildings somewhere near the

Victoria Memorial and I was telling Mala about Khanum’s Calcutta connection.

Her older sister, Mukhtar Begum, was a Punjabi gaanewali who had come to

the city in the 1920s to work for a Parsi-owned theatrical company. Within a

few years she had become a star of the Calcutta stage—she was advertised on

flyers as the “Bulbul-e-Punjab” (the Punjabi bulbul)-—and had moved into

a house on Rippon Street.

Khanum herself was born, sometime in the 1930s,

somewhere in these now-decrepit parts.

bring Khanum to next year’s festival. She also asked, in a sort of polite

murmur, “She’s still singing and all?”

“Of course!” I said, mainly to serve

my own interests: I had been looking for a reason—a ruse, really—to bring

Khanum to Calcutta and film her in the locations where she had passed her

childhood.

“Theek hai,” Mala said. “Let

me work on this.”

IT WAS A DIM JANUARY AFTERNOON IN

LAHORE, there was a power outage on Zahoor

Elahi Road, and Farida Khanum had finally woken up….I had come to prepare Khanum for a

concert she was to give in a week’s time in Calcutta, and was trying to engage

her, in this fragile early phase of her day, with innocuous-sounding questions:

which ghazals was she planning on singing there, and in what order?

“Do-tin cheezaan Agha Sahab diyan”

(Two-three items of Agha Sahib’s), she said in Punjabi, her voice cracking. She

was referring to the pre-Independence poet and playwright Agha Hashar Kashmiri.

“Daagh vi gaana jay” (You

must sing Daagh too), I said. “Othay sab Daagh de deewane ne” (Everyone

there is crazy about Daagh)—Daagh Dehlvi, the nineteenth-century poet.

me in appalled agreement, as if I had recognised an old vice of Calcutta’s citizens.

“Te do-tin cheezaan Faiz

Sahabdiyan vi gaadena” (And you can also sing two-three pieces from Faiz

Ahmad Faiz).

“Buss,” she said, meaning it

not as a termination (in the sense of “That’s enough”) but as a melancholy

deferral, something between “Alas” and “We’ll have to wait and see.”

I knew she was nervous about the

trip—the distance, the many flights, the high standards of Bengalis—and to

distract her I removed the lid of my harmonium and held down the Sa, Ga and Pa

of Bhairavi. I was chhero-ing the thumri ‘Baju band khul khul jaye.’

“Farida ji, ai kistaran ai?”

(How does it go, Farida ji?) I asked, all goading and familiar.

aalaap.

“Aaaaaa…” Her mouth was a

cave, her palm was held out like a mendicant’s.

pumped the bellows.

Her singing filled up the room: she

climbed atop the chords, spread out on them, did somersaults.

“Wah wah, Farida ji! Mein

kehnavaan kamal ho jayega! Calcutta valey deewane ho jaangey” (Bravo, Farida

ji! It will be extraordinary! The people of Calcutta will go crazy), I said.

away and making a sideways moue that managed to convey deliberation,

disinterest and derision all at once.

debility of the last three years, which has been accompanied by hospital

visits, physiotherapy and rounds of medication. (Khanum herself had described

it to me in terms of demonic sensations: her foot going numb, a tube entering

her throat, being forced to swallow strange pills and feeling a subsequent

whirling in her head.)

But worse, I had sensed, was the gloom accompanying this

illness—an awareness of the body’s vulnerability that led constantly to thoughts

of mortality, wistful ones not unlike those expressed in Khanum’s most famous

song, ‘Aaj jaane ki zid na karo’:

Waqt

ki qaid mein zindagi hai magar

Chand ghariyan yehi hein jo azaad hain

time’s cage is life, but

Some moments now are free)

The song is set in Aiman Kalyan, also

called Yaman Kalyan, the evening raag prescribed for creating a mood of

romance.

Her ‘Aaj jaane ki zid na karo’ is delivered in this

semi-free vein: her wilful, uneven pacing of the lyrics creates the illusion of

a chase, a constant fleeing of the words from the entrapments of beat. (This

technique, which has the mark of her teacher—the erratic and perennially

intoxicated Ustad Ashiq Ali Khan—bears its sweetest fruit in Khanum’s ghazals,

where strategic lags and compressions in the singing can enhance the pleasures

of a deferred rhyme.)

But what after these outlines have

been described? How to account for the slightly torn texture, the husky tone,

the maddening rass of the voice? And what to do about Khanum’s

devastating deployment of the word “haye” in the phrase “haye marr

jayeingey”? I once heard the Bollywood playback singer Rekha Bhardwaj say,

“Yeh gaana hai hee ‘haye’ pey” (This song is all about the ‘haye’).

I think she is right, in that Khanum’s transformation of that word—from a jerky

exclamation in the original to a dizzying upward glide, a veritable swoon, in

her own version—has made of it a mini-mauzu, or thematic locus, of the

lyric.

truncation in Khanum’s musical trajectory: she has said many times that

Partition, which resulted in the loss of her Amritsar home, signaled the end

of her training and forced her to make compromises—personal as well as musical.

For a few years, while living in the alien city of Rawalpindi, Khanum travelled

regularly to Lahore to sing for radio and act in films. But she failed to make

an impact. Soon she was consumed by marriage, and gave up singing at the

insistence of the industrialist who offered her the securities of a “settled

life.” Later, when she returned to music, she took up not khayal or thumri but

the accessible and mercifully “semi-classical” Urdu ghazal.

IN OCTOBER, three months before the concert in Calcutta, Farida Khanum

moved an audience in Lahore to tears.

This happened at the Khayal

Literature Festival. I was interviewing Khanum, in a session called “The Love

Song of Pakistan,” about her life in music. Adding star power to our panel was

the ghazal singer Ghulam Ali. I had spotted Ali—urbane in black kurta and

rimless glasses—in the audience at the start of the show and asked him to join

us with a spontaneous announcement.

“Farida ji,” I said, switching on

the shruti box I had placed before her. “Could you please, for just a little

bit, sing for us the bandish in Aiman that you learned as a child? Just

a little sample, please.”

This part was rehearsed. I had

suggested to Khanum earlier in the week that she present on stage a “thread” of

Aiman: she could start with a classical piece, then proceed to ghazals and

geets—including the crowd-pleasing ‘Aaj jaane ki zid na karo’—all in her

favorite raag. This would give our session a musical coherence, I had said, and

make it easy to follow.

“Achcha?” she had replied. “Sirf

Aiman karna ai?” (Really? You want to dwell only on Aiman?) She pressed her

lips together, in her inscrutable way. Then, with a mildly warning look, she

said, “Theekai. Ay achcha sochya ai.” (Okay. This sounds like a good

plan.)

Now, onstage, she ceded to my

request for the bandish with an indulging smile. What happened next surpassed

everyone’s expectations. Khanum’s voice, in contrast to her ailing frame, was

robust, full-throated, steady, flexible. Everything she sang glowed with

energy: she unfolded an aalaap, a bandish in teentaal, Faiz’s ghazal ‘Shaam-e-firaaq

ab na poochch,’ Sufi Tabassum’s ghazal ‘Woh mujhse huway humkalam’

and her signature ‘Aaj jaane ki zid na karo.’

She was bringing out the

raag in different forms, showing its familiar movements, making it reveal its

secrets. But she was also compressing a century of cultural evolution:

interspersing the singing with anecdotes about her childhood in Calcutta, the riaz

with her ustad in Amritsar, her post-Partition collaborations with poets

and music directors at Lahore’s radio station, and the fortuitous way in which

she had come to sing ‘Aaj jaane ki zid na karo’ (someone had asked her

to sing it at a mehfil). For the lay Lahore audience, the overall experience—one

of observing a constant or eternal thing (the raag) endure in ephemeral or

perishable forms—was eye-opening, cathartic and extra-musical.

In the case of a singer like Farida

Khanum, her role as a transmitter of djinns is magnified by social and

historical contexts. When she sings ‘Aaj jaane ki zid na karo,’ she is

passing on the cumulus of centuries—the laws of Aiman, according to one legend,

were fixed by Amir Khusro in the thirteenth century—in an accessible,

contemporary form. And the process is made poignant and ironic by our

ignorance: how many of the amateurs who upload videos of themselves singing ‘Aaj

jaane ki zid na karo’ on YouTube and Facebook know what they are really

channelling?

hurdle appeared. I had gone to the GD Birla Mandir, the venue of the show, for

a sound check. There I was told, an hour before the concert, that Khanum would

have to go down several flights of stairs in order to reach the auditorium.

“What are we going to do?” I asked

one of the organisers, a woman in a sari who looked back at me

uncomprehendingly.

Then she said, “Wait.”

Approximately twenty minutes later,

a little before 7 pm, a white car carrying Khanum pulled up to the GD Birla

Mandir. The legendary singer emerged in a pink-and-gold sari, and was led by

helpers and admirers into the foyer. Then the Mandir’s doors closed, and the

foyer emptied.

Khanum, who had only just sat down in a chair, spent the next

few minutes in a state of airborne transport, gripping the chair’s arms and

muttering the lord’s name under her breath, until she found herself seated in

her usual, regal way on a stage decorated with flowers. “Ya Ali Madad”

(Help me, Ali), she said, invoking the prophet’s heir and fourth caliph of

Islam, before the curtain went up.

“Ek muddat ho gayi hai” (It

has been an age), Khanum said, shivering a little but looking serene before her

Calcutta audience, which was comprised of young and old alike. “Innhon ne

kaha aap chalein, buss thhora sa safar hai” (They said I should

go, the journey is not long).

She stuck to the rules: she sang two

ghazals from Daagh, two from Faiz, the thumri in Bhairavi and ‘Aaj jaane ki

zid na karo.’ I had the privilege of sitting next to her on the stage and

holding open the book that contained the words to the songs. I marvelled at her

composure—and, yes, at the soundness of her training—when I saw how she

conducted the audience, the accompanying musicians and the sound technicians

behind the curtain with just her hand-movements and facial expressions. And I

saw—a novice observing a master, a mortal observing a living legend—how she

managed her voice: the expansions in the middle octave, the careful narrowing

at the higher notes, the strategic truncation of words and notes when she was

running out of breath. Occasionally, when I feared she was going to skip a

beat, I found myself clenching the book in my hands and glancing at the

audience for signs of a crisis.

But there were none, because even

the odd anti-climax, when it did occur, was a pleasure.

Link: – http://www.caravanmagazine.in/print/4357

…….

regards

Najma Heptullah- Parsis need help (not Muslims)

Najma Heptullah is no Uncle Tom. However we get the feeling that her priorities (as stated) are quite misplaced. The only way to help Parsis (while respecting the stricter than Brahmin blood-line rules) is to clone more Parsis. Then again, with her medical/biology background she may be able to achieve just that. Bravo!!!

If you have six children it is always important to see what you can

do for the weakest of them. So far as my ministry is concerned, of the

six minority communities the weakest is clearly the Parsis.

Dr Heptullah hails from a distinguished family (grand-niece of Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, cousin of Amir Khan). Heptullah has a Master’s degree in Zoology and a doctoral degree in

cardiac anatomy from the University of Colorado at Denver, in the USA. She has also been the Deputy Chairperson of Rajya Sabha (upper house, Indian Parliament) for 16 years and she is now the Minister of Minority Affairs and the sole muslim member in the Modi cabinet.

What is clear from her comments is that while muslims may not be unfairly targeted by this govt, they will remain invisible, as far as handouts are concerned.

The top demands from the community have been reservations in education and in jobs. These will not be implemented. To be fair, Congress has highlighted these demands many times (during elections), but has never made good on the promises. Also, efforts to introduce reservations for muslims at the state level (except in Tamil Nadu) have been stymied by the Courts.

The problem of reservations is a complex one. A reservation program for minorities will actually work out as a lose-lose proposition for muslims. The advanced minority communities (Christians, Jains, Sikhs) are likely to take disproportionate advantage of this provision. OTOH such a program would be vilified as a policy to appease the muslim vote-bank.

What is more promising (and legal) is a cut-out from the existing OBC reservation quota (4.5% was the Congress plank). Also, Dalit muslims (and Christians) can be made eligible for reservation benefits (this was first only for Hindus, later extended to Buddhists and Sikhs). However, to the extent the reservation pie is fixed, any quota for muslims will be fiercely opposed by the current Hindu beneficiaries.

Unfortunately, for the muslims, it looks like there are going to be only two viable coalitions going forward: (1) OBC + Forward caste team (and in select areas dalits as well) led by the BJP, and the (2) Dalit + Forward caste team led by Mayawati/BSP (which managed to secure the third highest vote percentage this elections (20%) but not a single seat). Neither group requires muslims, and will actually suffer if they are seen to be fishing for muslim votes (it will anger core supporters).

Due to H/M polarization, muslims at present have really no alternative but to vote for the Congress (A, B, C teams). There is also polarization within muslims, the BJP can expect to win the Shia and Bohra vote (these communities are relatively advanced and would not be seeking reservation benefits anyway). Since the “secular” parties do not have to earn the muslim votes, they will promise a lot and forget quickly (which is the case for the last 65 years). If anything, the track record of non-BJP governments in preventing riots is worse than that of the BJP governments.

Finally, as has happened already in Axom and in Kerala (and Hyderabad), there are viable right-wing muslim parties which have the advantage (from a muslim standpoint) of being for, of and by muslims (conservatives). These parties may grow in strength in other parts of India as well (next stop West Bengal, Bihar and Uttar Pradesh). If that happens, the secular parties will be wiped out (in a first past the post system) and BJP will win the mantle of the “natural ruling party” of India.

There are secular solutions to the above problems and a party like the Aam Admi Party should be able to champion such solutions and even win a mandate based on such a charter. A huge, diverse country like India is best represented by some modified form of proportional representation. Also the concept of reservations can be revisited and the targeting of communities can be in terms of economic backwardness.

Dalits and Muslims (the two most disadvantaged groups) are likely to benefit strongly from such arrangement(s). This is then the “social justice” gap that Indian democracy requires fixing (as fast as possible). It is important for the sake of the country that a left-secular organization like the AAP switches off the dramabazi and focuses on building bridges with the voters (which has been badly bruised by the 49-day tenure in Delhi).

It is surprising that Arundhati Roy (who was voted as the leading thinker in the world) has not proposed such (and other) practical measures which will move both secularism and democracy forward. But then as Omar says, it is not clear that the Pankajists will be happy if this actually happened by some miracle. They have found out that throwing stones from the outside is a hugely profitable business, thus it is unlikely that any help will be forthcoming from them any time soon.

………

Minority Affairs Minister Najma Heptullah has said Muslims are too large

in number to call themselves a minority and that it is the Parsis who

need special attention, for they are a “minuscule minority”.

Referring to the issue of Muslim reservation in jobs, she said “there

is no provision in the Constitution for religion-based reservation”.

The matter is in the Supreme Court.

…

“If you have six children it is always important to see what you can

do for the weakest of them. So far as my ministry is concerned, of the

six minority communities the weakest is clearly the Parsis. They are a

minuscule minority that is so ‘ Muslims too many to be called minority,

it’s Parsis who need special attention’ precariously placed that one

needs to take care of their survival. Muslims really are too large in

number to be called a minority community,” the minister told The Indian

Express.

…

She said the very concept of minority and majority is relative and

when talking about minorities it is imperative to understand that it is a

term that encompasses many parameters, including language, apart from

religion. Neither is there a ‘one-size-fits-all’ formula for the welfare

of minorities.

…

The Ministry of Minority Affairs was set up in 2006 in the wake of

the appointment of the Sachar Committee by the then prime minister

Manmohan Singh to look into social, educational and economic conditions

of Muslims in India. Though it caters to all six minority communities —

the latest addition being Jains — Muslims have, since its inception,

been a special focus area for the ministry.

…

Heptullah is yet to get a full lowdown on the ministry’s programmes

and schemes, but one scheme that she is not inclined towards is the

Prime Minister’s 15-point programme for minority concentration areas.

“It was started by Indira Gandhi in 1980 and in these 34 years all that

has happened is that successive prime ministers have merely ‘inherited’

it without any real thrust on implementation. I will have to discuss

with Narendra Modiji whether he really wants to inherit it. It is

striking that it has remained at 15 points all this while without one

addition or deletion which should have happened if there was application

of mind,” she said.

…

Heptullah made no bones about her aversion to the idea of reservation,

maintaining that it cannot be a solution for anything. “I am not in

favour of reservation. I have come this far without reservation. What is

important is positive action to provide level playing field. Once we do

that politically, socially and educationally they will be able to

compete with the rest.”

………………..

Link: http://indianexpress.com/article/india/politics/muslims-too-many-to-be-called-minority-its-parsis-who-need-special-attention/99/

…..

regards

Irom Chanu Sharmila- (Hindu) Terrorist?

She is Gandhian no. 1 of the nation, the captain of a single-woman non-cooperation movement, without any support from any big name or big money.

I never voted as I had lost faith in democracy, but

the rise of the new anti-corruption party, Aam Aadmi Party, changed my

thinking.

She has now expressed interest in meeting with PM Modi. She is very hopeful that her single point request: repealing the Armed Forces Special Powers Act will be granted (we are not hopeful at all, in simple terms the Army has a veto and will exercise it).

Najma Heptullah, the minorities minister and grand niece of freedom fighter Abdul Kalam Azad, has created a firestorm by saying that muslims in India are too large a population to be considered a minority (unlike Parsis). As long as we are in blunt talking mode, we should also acknowledge that Hindus are not one unified block either (unlike what the Hindutva movement would have us believe).

Not only do we have Hindu minorities who face discrimination from the Hindu majority (Bihari migrants in Maharashtra, for example) but some Hindu groups are actually in a state of opposition to actions of the Indian state. Most of these groups are in the North-East and the most prominent amongst them is the United Liberation Front of Axom (ULFA).

……..

An Indian activist who has been on hunger strike for over 13

years said on Wednesday she was pinning her hopes of finally leading a

normal life on new Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

Irom

Sharmila, 42, who is force-fed by a drip through her nose, said she

wanted to meet Modi in hopes of ending the military’s alleged human

rights abuses in her northeastern home state of Manipur.

Escorted

by more than a dozen police officers, Sharmila appeared in a court in

New Delhi in connection with long-running charges against her of

attempting to commit suicide, a crime in India.

Sharmila told a

judge that she wanted a “settled life as others do” but would not break

her fast until a controversial law that covers large parts of restive

northeastern India and Kashmir was repealed

…….

[Ref. Wiki]

November 2000, in Malom, a town in the Imphal Valley of Manipur, ten civilians were

shot and killed while waiting at a bus stop. The incident, known as the

“Malom Massacre,” was allegedly committed by the Assam

Rifles, one of the Indian

Paramilitary forces operating in the state. The victims included Leisangbam

Ibetombi, a 62-year old woman, and 18-year old Sinam Chandramani, a 1988

National Child Bravery Award winner.

who was 28 at the time, began to fast in protest of the killings, taking

neither food nor water. As her brother Irom Singhajit Singh

recalled, “It was a Thursday. Sharmila used to fast on Thursdays since she

was a child. That day she was fasting too. She has just continued with her

fast”

days after she began her strike, she was arrested by the police and charged

with an “attempt to commit suicide”, which is unlawful under the Indian Penal Code (IPC), and was later

transferred to judicial custody. Her health deteriorated rapidly, and nasogastric intubation

was forced on her in order to keep her alive while under arrest.

Sharmila has been regularly released and re-arrested every year since her

hunger strike began under IPC section 309. The law declares

that a person who “attempts to commit suicide … shall be punished with

simple imprisonment for a term which may extend to one year [or with fine, or

with both].”

primary demand to the Indian government is the complete repeal of the AFSPA which has been blamed for violence in

Manipur and other parts of northeast India.

Sharmila had become an “icon of public resistance.” Following her procedural release on 2

October 2006 Irom Sharmila Chanu

went to Raj Ghat, New Delhi, which she said was “to

pay floral tribute to my idol, Mahatma Gandhi.”

October, she was re-arrested by the Delhi police for attempting suicide and was

taken to the All

India Institute of Medical Sciences, where she wrote letters to the

Prime Minister, the President, and the Home Minister. At this time, she met and won the

support of Nobel-laureate Shirin Ebadi, the

Nobel Laureate and human rights activist, who promised to take up Sharmila’s

cause at the United

Nations Human Rights Council.

she invited anti-corruption activist Anna Hazare to visit Manipur, and Hazare sent two representatives to

meet with her.

eleventh year of her fast, Sharmila again called on Prime Minister Manmohan Singh to repeal the law.

October 2013 Amnesty India issued a press release recognising Irom Sharmila as

a “‘Prisoner of Conscience’, who is being held solely for a peaceful

expression of her beliefs.”

also offered to contest Lok Sabha polls by Aam Aadmi Party leader Prashant Bhushan from Inner

Manipur under his party’s banner through Just Peace Foundation (JPF), a

solidarity group supporting Sharmila’s struggle.

rejected Aam Aadmi Party’s offer to contest the Lok Sabha polls and said that

“Though I support AAP, I rejected the offer as I’m just a protester not a

politician.” She also showed her moral support to the party and said

“If I am allowed to vote, I will cast my vote in favour of the AAP which I

am confident will restore the rule of democracy.”

offers on contesting Lok Sabha polls ,a JPF trustee said that “Politics is

not a cup of her (Sharmila) tea and she even called politicians ‘shameless

people’ for failing to scrap AFSPA despite their countless promises.”

she showed willingness to cast her vote and submitted an application

expressing her desire and she mentioned that “I never voted as I had lost

faith in democracy, but the rise of the new anti-corruption party, Aam Aadmi

Party, changed my thinking.” But she was not allowed to cast her vote as

per the law. An Election Commission official explained the reason stating that

under Section 62 (5) of the Representation of the People Act, 1951, a person

confined in jail cannot vote.

……

Link: http://www.dawn.com/news/1109200/13-year-long-hunger-striker-pins-hopes-on-modi

…….

regards

Apprehensively Optimistic

are simply too high for partisanship, and there are certain things that only someone

like Narendra Modi can do on the Indian side – just as only Nixon could go to

China and only Begin make peace with Egypt. I hope Mr. Modi has the wisdom to see this and the courage

to act. On the Pakistani side, Nawaz Sharif is probably better placed to act

towards rapprochement than the previous government of the Pakistan Peoples’ Party, but I’m not sure he has

enough freedom to act. Recent weeks have demonstrated that the strings of power

in Pakistan are still pulled by invisible actors who are ruthless, rigid and unburdened by conscience. However, there is a little

room for hope. Though the Nawaz government was not able to stand up fully to

the assault from the Deep State in the matter of Geo TV, it did not completely buckle

under either. Its surrogates pushed back forcefully – if only verbally – and a

degree of moral support for Geo was orchestrated from the chattering classes.

The clash is far from settled, but if the Nihari Caucus emerges from this with

some sort of settlement (the technical term in Pakistan is “muk-muka”), they

may find the guts to move on the infinitely more important issue of rationalizing

relations with India.

whether the Modi government will have the fortitude to remain rational in the

face of provocations that will surely come their way from both the Pakistani

Deep State and their own right-wing. Only a strong government can resist the temptation to lash out, but

this is the strongest government India has had in decades. I, for one, actually

hope that, during their meeting, the two prime ministers hatched some secret

plots and set some hidden agendas, for in this age of screaming TV pundits, the

surest indication of serious ideas is that they cannot be revealed in public.

A friend asked me how I felt about the outcome of

the Indian elections. My answer was “apprehensively optimistic”.

That’s where we are today. May the apprehensions diminish and the optimism

grow!