I have been too busy (or wasting too much time on twitter) to write much, but I think we should promote some essays from other sites when they look interesting. Here is one I saw today: David Berlinski reviews Pankaj Mishra’s latest book of essays. You can read it in full on this link.

(my own, less erudite and much more rant-like takedown of Mishra and his brand of “tailor made for Western and Westernized Liberals” shtick can be found here) . (my own summary of Pankaj in that rant: With Pankaj, the safest bet is that he is “not even wrong”. Good for virtue signaling. Useless for any other purpose.) You can also read a review of sorts I wrote about Pankaj in 2014 that also tries to clarify where I am coming from in this topic)

A few excerpts:

PANKAJ MISHRA is an Indian journalist, novelist, and travel writer; he is widely appreciated as a scold. Written between 2008 and just the other day, the sixteen essays comprising Bland Fanatics were published variously in The Guardian, The London Review of Books, the New Yorker, The New York Times, and The New York Review of Books. Readers seeking ideological exuberance must look elsewhere. The essays are themselves unified by a common rhetorical strategy, if not a common rhetorical subject, in which Mishra reveals that he knows something that others do not. “It had long been clear to me,” he writes, “that Western ideologues during the Cold War absurdly prettified the rise of the ‘democratic’ West.”

What I didn’t realise until I started to inhabit the knowledge ecosystems of London and New York is how evasions and suppressions had resulted, over time, in a massive store of defective knowledge about the West and the non-West alike. Simple-minded and misleading ideas and assumptions, drawn from this blinkered history, had come to shape the speeches of Western statesmen, think tank reports and newspaper editorials, while supplying fuel to countless log-rolling columnists, television pundits and terrorism experts.

Living on hot air, logrolling columnists, like certain abstemious yogis, do not generally require fuel, although they may require logs; and a knowledge ecosystem suggests nothing so much as a child’s terrarium: wood, water, weeds, worms. Never mind. Readers will get the point. They could hardly miss it. In hanging around London and New York, Mishra encountered a good many dopes.

No doubt…

… THE ESSAYS IN Bland Fanatics, if intelligent and brisk, are also imperfectly argued and badly written. Realities are brutal, falsehoods blatant, notions reek, prejudices are entrenched, binaries pop up here and there (eager, I am sure, to escape gender confinement), crime rates skyrocket, adventurers are bumptious, history is blinkered, delusions climax, despotisms are ruthless, and, if breasts are not being bared, chests, at least, are being thumped. Mishra is also a writer unwilling to savor the niceties of attribution. The wonderful phrase “closing time in the garden of the West” appears three times in two essays, welcome relief from the clump of Mishra’s habitual clichés. It is due to Cyril Connolly. That “every document of civilization is also a document of barbarism” is due, in turn, to Walter Benjamin. Mishra has appropriated the phrase and its mistranslation into English.

Continue reading David Berlinski Reviews Pankaj Mishra

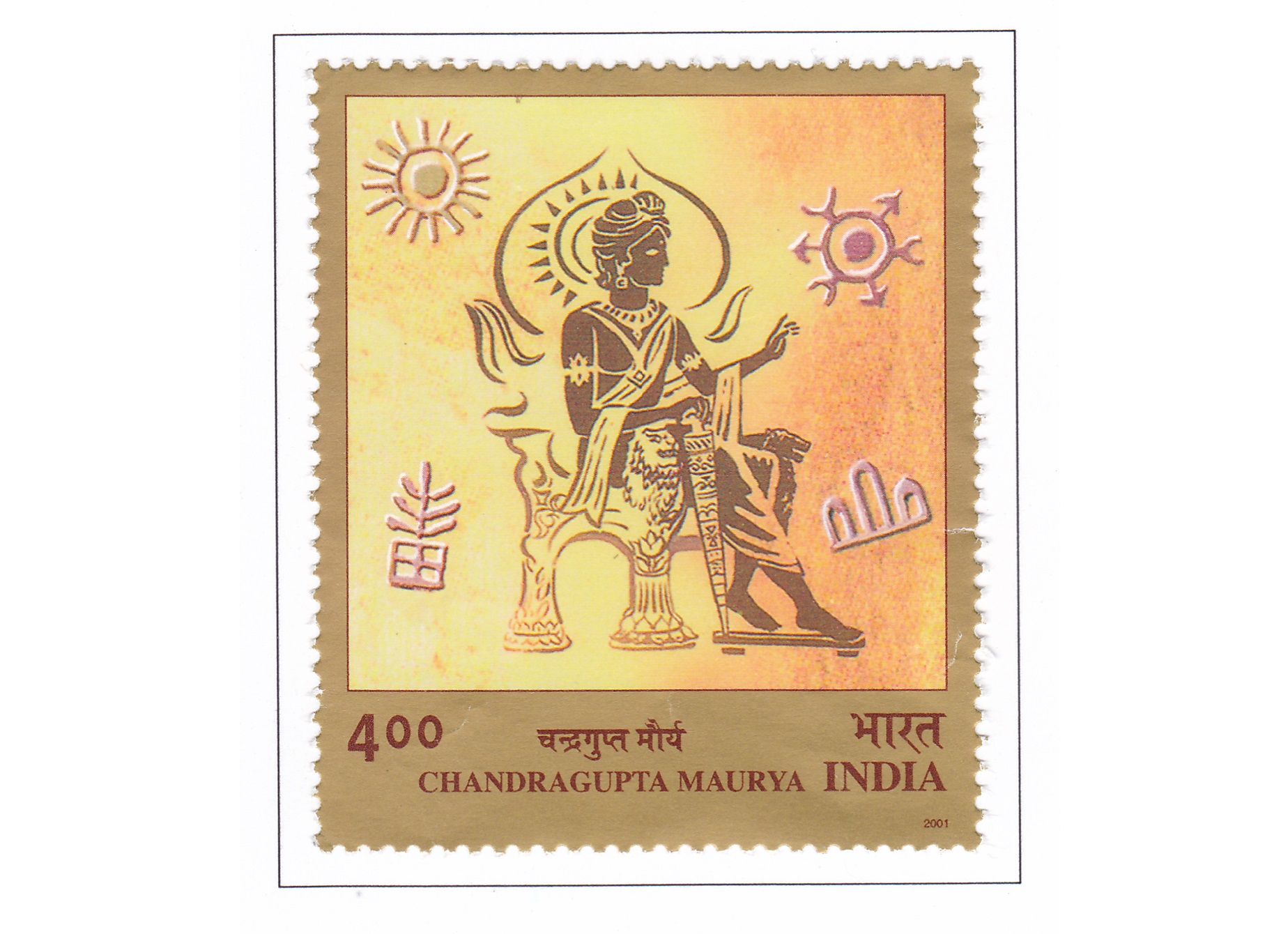

Gold coin of Chandragupta I with his wife Kumaradevi

Gold coin of Chandragupta I with his wife Kumaradevi