This translation was originally published in The Peshawar Review earlier this month. It is an excerpt from my translation of “Sphygmomanometer”, one of the Urdu short stories included in Bilal Hasan Minto’s collection Model Town (Sanjh Publications 2015). The collection consists of linked short stories set in Lahore in the late 1970s and early 1980s — at the beginning of General Zia ul Haq’s martial law. The narrator of these stories is an adolescent boy who comments on the hypocrisies of the adults around him.

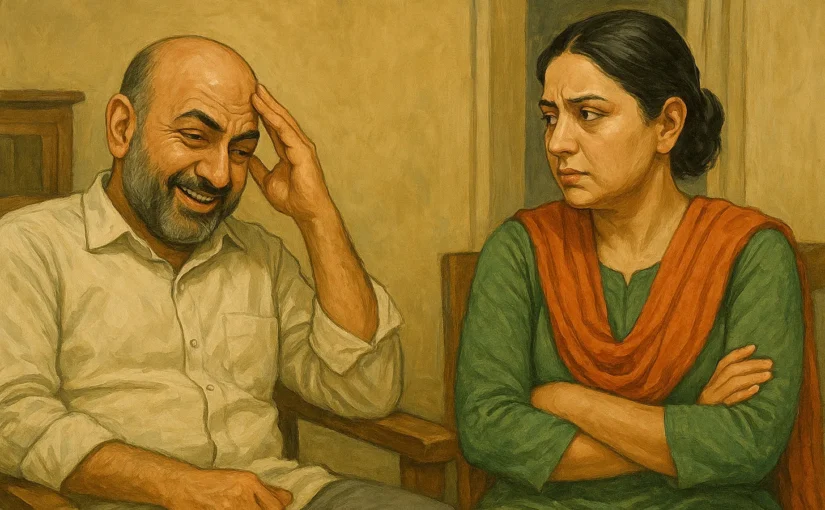

One day, Naveed Bhai hadn’t returned from college by five o’clock. Usually, this wouldn’t have been cause for concern — a slight delay in returning home. But, over the past few days, Naveed Bhai had been behaving in a way that caused Abba to worry that he might be getting involved in something that would land him in trouble with the government of the cartoonish General Zia. Sitting at the dining table one day, Naveed Bhai had said angrily, through clenched teeth, that “we should teach these ignorant student union thugs a lesson.” On hearing this, Abba stared at him and said they had sent him there to study, not to get involved in useless things. Naveed Bhai should go straight to college and come right back. He shouldn’t even think about getting involved in union affairs and getting mixed up with dangerous people. Instead of being quiet after this reprimand, Naveed Bhai started speaking even more loudly:

“They are thugs! Their legs should be broken the way they broke Junaid’s. General Zia is behind them!”

Alarm bells had gone off in Abba’s head once before when Naveed Bhai had said he was going to join an underground group of progressive, pro-democracy students. Abba had only gently rebuked him, saying that future doctors shouldn’t get involved in such nonsense. Student unions were against the law. There was no need to get himself in trouble.

Who knows who he was, poor Junaid, whose legs had been broken. And I didn’t even know what a ‘union’ was but when Abba and Naveed Bhai started arguing loudly, I figured some dangerous people had become members of a student group sponsored by a political party, and now they were hovering around colleges and universities. The party they were affiliated with considered itself the last word on religion, and its sole champion. From Abba and Naveed Bhai’s conversation, I also gathered that these political workers used to beat students and coerce them into obeying strange orders. For example, boys and girls could not walk together on the street. If an emergency forced a boy to talk to a girl, neither of them was to be heard laughing — but such an emergency should never occur. Similar illogical things spewed from their strange minds, like the vomit from Faizan’s mouth. They had always done things like this, on behalf of that criminal general with the cartoon face and never did anything commendable just as that shameless general hadn’t either.

When Abba heard from Naveed Bhai about poor Junaid’s broken legs he became even more worried. Pointing his finger for emphasis, he warned, “Don’t you dare get involved in such things!” Continue reading Sphygmomanometer (Excerpt)–Translation from the Urdu