“Pakistan army remains the only one after WW2 to have carried out a large scale genocide. The comparison to the Nazis is a fact-based one. Mentioning this simple historical fact isn’t “anti-Pakistan”. RNJ

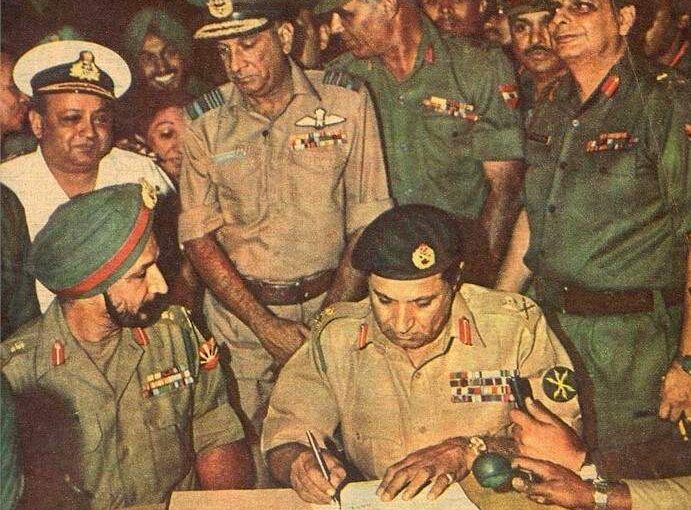

The events of 1971 in East Pakistan involved large-scale violence, mass civilian deaths, displacement, and grave violations of humanitarian norms. These facts are not contested. What remains contested is classification.

The term genocide is not a moral adjective but a legal category. It requires the demonstration of specific intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a protected group as such. Whether the actions of the Pakistan Army in 1971 meet that threshold has been debated for decades by historians, jurists, and international bodies. No international tribunal has issued a binding legal determination on this question.

It is therefore inaccurate to treat the classification as settled fact.

It is also inaccurate to claim uniqueness. Multiple post-1945 cases involve mass killing by state or quasi-state forces, including Cambodia, Rwanda, Bosnia, Indonesia in East Timor, Ethiopia under the Derg, Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, and others. These cases differ in scale, intent, structure, and outcome, but they collectively demonstrate that mass atrocity is not unique to any one army or state.

Comparisons to Nazism further complicate rather than clarify analysis. The Holocaust was a centrally planned, ideologically explicit project of total extermination, executed with industrial precision. Analogising disparate historical events to that case risks collapsing distinct phenomena into a single moral category, which weakens rather than strengthens historical understanding.

This does not absolve responsibility. It delineates it.

Criticism of military institutions, including allegations of political dominance, economic privilege, or abuse of power, is a legitimate subject of inquiry. Such criticism must, however, remain analytically separable from claims about national character or civilisational guilt. States are not monoliths, and neither armies nor populations are uniform actors across time.

The same standard applies across cases. If the use of maximalist language would be considered inappropriate or inflammatory in one national context, it should be treated similarly in another. Consistency is a requirement of serious analysis.

The function of historical discussion is not to allocate collective shame, but to establish responsibility with precision. When legal terms are used loosely, they lose their meaning. When moral language escalates without discipline, it ceases to persuade and begins to polarise.

The appropriate posture, therefore, is neither denial nor rhetorical excess, but restraint. Atrocity should be documented. Responsibility should be apportioned. Language should be exact.

Anything else substitutes heat for clarity.