From my Substack:

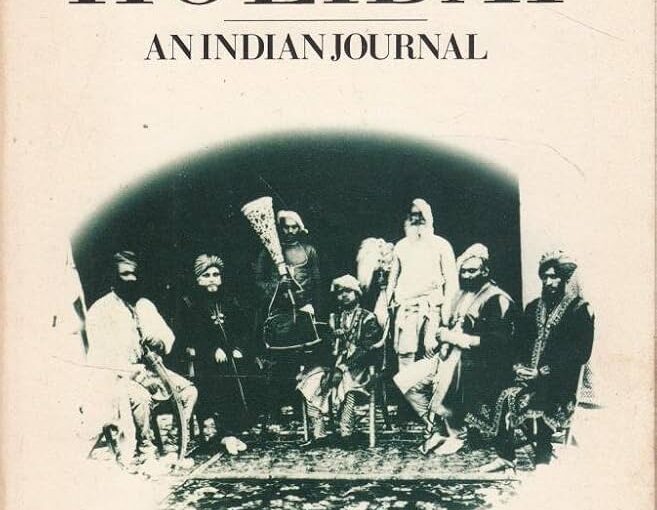

J.R. Ackerley’s Hindoo Holiday–originally published in 1932–tells the story of the five months (December 1923-May 1924) he spent as secretary to Maharaja Vishwanath Singh of Chhaturpur (called “Chhokrapur” in the book). In his “Explanation”, Ackerley describes the Maharaja’s motivations for hiring a private secretary from England. He writes:

He wanted someone to love him–His Highness, I mean; that was his real need, I think. He alleged other reasons, of course–an English private secretary, a tutor for his son; for he wasn’t really a bit like the Roman Emperors, and had to make excuses.

As a matter of fact, he had a private secretary already, though an Indian one, and his son was only two years old; but no doubt he felt that the British Raj, in the person of the Political Agent who kept an eye on the State expenditure and other things, would prefer a label–any of the tidy buff labels that the official mind is trained to recognize and understand–to being told ‘I want someone to love me.’ But that, I believe, was his real reason nevertheless.

In his initial meeting with Ackerley, the Maharaja asks him if he has read certain books as he wants them explained to him. Ackerley writes:

His highness seemed very disappointed. I didn’t know what ‘Pragmatism’ meant, and had read practically none of the authors he named. I must read them at once, he said, for they were all very good authors indeed, and he wished me to explain them to him. He had them all in his library in the Palace; I must get them out and read them… (9)

Later, in the same conversation, the Maharaja wants Ackerley to settle the question of the existence of God. Ackerley writes:

‘Is there a God or is there no God?’ rapped out His Highness impatiently. ‘That is the question. That is what I want to know. Spencer says there is a God, Lewes says no. So you must read them, Mr. Ackerley, and tell me which of them is right (9)

This interaction immediately characterizes the Maharaja and sets the tone for the rest of the book.

One of the noteworthy features of the book is the homoerotic content. Ackerley was openly gay–which was very unusual at the time since homosexual behavior was illegal in the UK. The Maharaja was also homosexual and much of the humor of the book revolves around his attractions to various young men. For example:

This encouraged him, and he reached the subject of friendship as understood by the classic Greeks, and spoke of a book he had in his library which contained some beautiful photographs of Greek and Roman statuary. But now, he said, young men were never wholly beautiful. Some had beautiful faces, but ugly bodies; some beautiful faces and bodies, but ugly hands or feet; some very physically completely beautiful, but these were stupid–and spiritual beauty alone was not enough.

‘There must be beautiful form to excite my cupidity,’ he said.

‘Your what, Maharaja Sahib?’

‘Cupidity. What does it mean?’

‘Lust’

‘But you have Cupid, the God of Love?’… (27)

In his article “Seventy years of Hindoo Holiday” (Himal Southasian 01 October 2002), Hemant Sareen writes:

Many social trends noticeable in today’s India were current in Ackerley’s India: the continuing preference for ‘Indian treatment’ (ayurvedic) over the ‘Western/ European system’ (allopathic), or the pragmatism that makes Babaji Rao, a strict vegetarian, put aside his qualms and administer “Brand’s Essence of Chicken” (his “face puckered with disgust as he uttered these dreadful words”) to his ailing son. Even the disregard for the caste system among the liberal elite, though that has become suspect post-Mandal (1990), is reflected in the book, as is the desire for self-improvement and hunger for education, which are still seen as a means of material and spiritual uplift.

On the flip side, on view are the warped Indian sense of judgement, a morality easily inveigled by expedience and an exaggerated sense of dignity marked by an inclination to servility. Women were the inconsequential gender in the Indian scheme of things, hardly visible. “Don’t notice them! They don’t exist”, an Englishwoman cautions the debutant Ackerley against seeking the company of Indian women. India may be the land of cohabiting opposites: sex with abstinence, snake with mongoose, deification with desecration, modernity with orthodoxy. Hardly an easy picture to understand, but, nonetheless, a true one. Ignoring the evidence of who we Indians are and how we once were impoverishes and diminishes our humanity – perhaps our only significant contribution to the world.

In conclusion, Hindoo Holiday is a lighthearted read that provides insight into a bygone historical era. I would highly recommend it to those who are interested in South Asia.