While any discussion of Partition tends to focus a lot on the migrations and violence circa 1947, we tend to forget the mayhem that followed in Bengal with a lag. As late as 1950! In Bengal the violence peaked in late 1949 – 1950 unlike in Punjab. Particularly in East Pakistan.

The discussion of these riots and the agreements that ensued in 1950 in TCA Raghavan’s book “The People Next Door” make an interesting read.

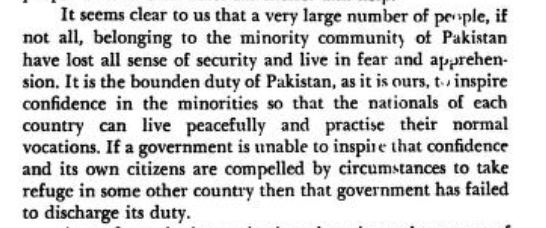

The partition in 1947 had left both sides of Bengal with similar proportions of minority populations. West Bengal had five million Muslims in a population of twenty one million. East Pakistan was left with eleven million Hindus in a population of thirty nine million.

Unlike in the Punjab, a full-fledged ethnic cleansing did not occur in Bengal. Perhaps in part because of the presence of Gandhi in Bengal for a couple of crucial months in 1947. There could be other reasons that can explain why Bengal didn’t start with a blank slate unlike Punjab. I can only think of the Gandhi-factor as of now

The violence festered in Bengal right up to 1950, but it peaked in the month of February that year, particularly in East Pakistan. The violence against Hindus provoked much political unrest in India, causing Nehru to assume stances that seem very hawkish to us today.

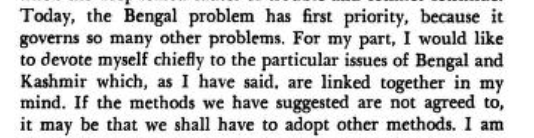

Jawaharlal Nehru addressed the Parliament on Feb 23rd of 1950, expressing outrage at the East Pakistan riots

Then he went on to suggest a possible military action against East Pakistan while concluding his speech – Note the words – “We shall have to adopt other methods”

But then the invasion idea was dropped. It was not just a question of Nehru being pusillanimous. The President of India, Rajendra Prasad, a supposed right winger, wrote a letter to Nehru, suggesting that he drop the idea of attacking / annexing East Pakistan!

I find this curious.

An interesting example of a “conservative” voice in India (Rajendra Prasad) persuading the supposedly more dovish and liberal Nehru to drop the idea of military action against East Pakistan

Another thing that I find curious about this episode is that the very large scale migrations that ensued in early 1950, were mostly undone by the end of the year by reverse migrations, following the Nehru-Liaquat agreement in April 1950.

Between February 7th and April 8th 1950, 1.5 million people crossed the borders! 850K Hindus from East Pakistan to West Bengal, and 650K Muslims from West Bengal to East Pakistan.

The agreement was signed on 8th April 1950, but it did not reverse the migration tide immediately. Between 9th April and 25th July, 1.2 million more Hindus left East Pakistan for India, while only 600K returned back to Pakistan prompted by the agreement. That’s roughly a return-ratio of 1 in 2.

But it appears the ratio was much better for Muslims for exactly the same period (9th April to 25th July) following the treaty. In this timeframe, 450K Muslims left West Bengal for East Pakistan, but 300K returned back. That’s a ratio of 2 in 3.

So it appears the agreement reassured the Muslims more than it did the Hindus. But nevertheless it did prompt Hindus to return back to East Pakistan in larger numbers by the end of the year. A million Hindus had returned back to East Pakistan by December of that year.

One wonders if we could’ve had a more peaceful subcontinent in later decades, had the powers that be sat down and planned a more systematic population transfer, instead of idealistic reassurances to minorities, which did help stall the large scale transfer in the short run, but kept communal tensions simmering for several more decades.

References:

- TCA Raghavan’s “The People Next Door”

- Jawaharlal Nehru’s Speeches, Vol II

The author tweets @shrikanth_krish