Category: Uncategorized

Why Hinduism is not inchoate paganism

An individual, who I have come to conclude is a troll after further comments (they are banned), mentioned offhand that Hinduism and/or Hindu identity is reactive Islam and the British, and that its origins are in the 19th century. This is a common assertion and presented recently by one of our podcast guests. I myself have entertained it in the past. It’s not prima facie crazy.

An individual, who I have come to conclude is a troll after further comments (they are banned), mentioned offhand that Hinduism and/or Hindu identity is reactive Islam and the British, and that its origins are in the 19th century. This is a common assertion and presented recently by one of our podcast guests. I myself have entertained it in the past. It’s not prima facie crazy.

But I have come to conclude that this is not the right way to think about it. Or, more precisely, it misleads people on the nature of the dynamic of Indian religious identity and its deep origins. This is why I think Hindus themselves self-labeling ‘polytheists’ or ‘pagan’ can mislead people. Not because these are offensive terms. People can refer to themselves however they want. But these terms have particular relational resonances with other groups, periods, and peoples.

One can point to al-Biruni’s external observations about Indian religion, or Shijavi’s personal opinions in his correspondence, to make a case for Hinduism and Hindu identity (using both terms to avoid troll-semantic ripostes) being older than the 19th century. But this is not the argument that is strongest to me. I have spent many years and books reading about the cross-cultural emergence of religious identity, and its change, in places as diverse as Classical Rome, post-Arab conquest Iran, and 7th century Japan, to name a few places. Many of these places and times had local religious cults and practices. In all of these places, they were assimilated and absorbed into the intrusive “meta-ethnic” religion. In Rome, Tibet, and Japan, the religion had major initial setbacks, but eventually, the meta-ethnic “higher religion” came back and captured the elite.

In the modern world, we see massive Christianization, and to a lesser extent Islamicization, in Sub-Saharan African. The traditional religions persist, in particular in West Africa, but history is clearly against them. Importantly, most of the religious change occurred after the end of colonialization.

The relevance of this is clear. The Indian subcontinent would be an exception for all these above cases if the vast majority of people were unintegrated animists with only local religious cults. The precedent from Europe and the world of Islam is that Brahmins and a few other pan-Indian groups (e.g., Jains) would persist as religious minorities, while the vast majority converted to the newly introduced meta-ethnic religion.

The relevance of this is clear. The Indian subcontinent would be an exception for all these above cases if the vast majority of people were unintegrated animists with only local religious cults. The precedent from Europe and the world of Islam is that Brahmins and a few other pan-Indian groups (e.g., Jains) would persist as religious minorities, while the vast majority converted to the newly introduced meta-ethnic religion.

Kashmiri Brahmins are just like other Kashmiris

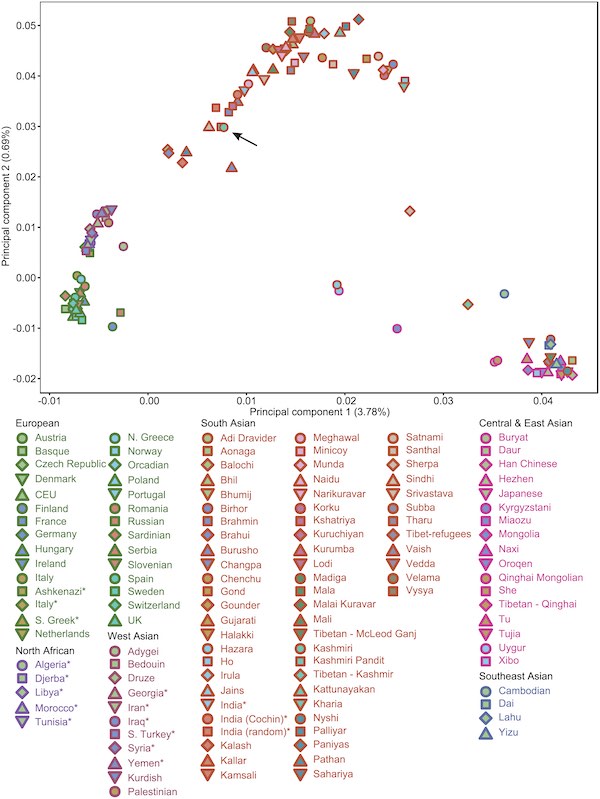

I think I’ve posted this before, but it was a while ago before we had so many readers. In this paper they took 15 random Kashmiris from the Valley, and compared them to various populations. The plot below, as well as admixture analysis in the paper, shows no daylight between the Pandit samples and generic Muslim Kashmiris.

This is not to say Pandits are not an endogamous community and were not before the Islamicization of Kashmir. But, it is to say that in their overall genome their origins are exactly the same as other Kashmiris. This is in contrast to many parts of India in regards to Brahmins, though the “stylized fact” seems to be the further north and west you go, the smaller the genome-wide difference between Brahmins and non-Brahmins will be. This seems to comport with the idea that Brahmins are intrusive to the south and east in a way they are not to the north and west.

Finally, the data from ancient DNA is strongly suggestive of “AASI-reflux” across north and west South Asia after 3000 BC. See my post The Aryan Integration Theory (AIT).

Endogamy and assimilation: Parsis in India

The Guardian has a long piece about Parsis, The last of the Zoroastrians. The author is the child of a Parsi mother who married a white Briton. Though he brings his own perspective into the piece, I appreciated that he did not let it overwhelm the overall narrative. The star are the Parsis themselves, not his own personal journey and viewpoints.

The Guardian has a long piece about Parsis, The last of the Zoroastrians. The author is the child of a Parsi mother who married a white Briton. Though he brings his own perspective into the piece, I appreciated that he did not let it overwhelm the overall narrative. The star are the Parsis themselves, not his own personal journey and viewpoints.

In relation to the Parsis, there are two aspects in the Indian context that warrant exploration

– high levels of cultural assimilation

– high levels of cultural separateness

These seem strange outside of India, but they make sense within India. The Zoroastrian priests who migrated to what became Gujurat integrated themselves into the local landscape as an endogamous community. From a genetic perspective, the best overview is “Like sugar in milk”: reconstructing the genetic history of the Parsi population:

Among present-day populations, the Parsis are genetically closest to Iranian and the Caucasus populations rather than their South Asian neighbors. They also share the highest number of haplotypes with present-day Iranians and we estimate that the admixture of the Parsis with Indian populations occurred ~1,200 years ago. Enriched homozygosity in the Parsi reflects their recent isolation and inbreeding. We also observed 48% South-Asian-specific mitochondrial lineages among the ancient samples, which might have resulted from the assimilation of local females during the initial settlement. Finally, we show that Parsis are genetically closer to Neolithic Iranians than to modern Iranians, who have witnessed a more recent wave of admixture from the Near East.

The major finding is that most of the ancestry, on the order of 75%, of Indian Parsis is generically Iranian. On the order of 25% is “indigenous”, probably Gujurati. The fact that the proportion of mtDNA, the maternal lineage, is closer to 50% in both modern and ancient samples, indicates that the mixing with Indians occurred through taking local women as brides. Further genetic investigation in the above paper suggests that this was not a recurrent feature. In other words, once the Zoroastrian community in Gujurat was large enough, it became entirely endogamous.

And yet the Parsis speak Gujurati (or in Pakistan Sindhi and Urdu), and in many ways are culturally quite indigenized.

I bring this up because this portion of the above piece I’ve seen elsewhere:

The small community of Iranian Zoroastrians is even more liberal, allowing female priests, and there are also nascent neo-Zoroastrian movements in parts of the Middle East.

I have read repeatedly that Iranian Zoroastrians are more “liberal” when it comes to the issue of religious endogamy. The term “liberal” indicates innovation. But if you look at the historiography it seems clear that though Zoroastrianism was strongly connected to Iranian-speaking people, it was not exclusive to them. Zoroastrianism was cultivated and encouraged by the Sassanians in much of the Caucasus, and it spread into Central Asia, even amongst some Turkic groups, before the rise of Islam.

Zoroastrianism was not aggressively proselytizing but before 600 A.D. neither was Christianity outside of the Roman Empire. This is not a well-known fact due to the religion’s gradual diffusion to non-Roman societies, such as Ireland and Ethiopia, but before Gregory the Great missions to barbarian peoples were not organized from the Metropole but were ad hoc (the Byzantines eventually began centrally organized missionary activities after 600 A.D., but they were never as thorough or enthusiastic as the Western Christians). Our understanding of Zoroastrianism then may not be clear because the religion went into decline during a transformative period in world history when the religious boundaries and formations we see around us were still inchoate.

The major takeaway from all this is that strenuous Parsi arguments for the ethnic character of Zoroastrianism are a reflection not of their Iranian religious background, but their Indian cultural milieu. Zoroastrian “traditionalists” in India are actually Indian traditionalists, who have internalized an innovation to allow for integration into South Asia. And, I would argue some of the same applies to Indian “traditionalists,” whose cultural adaptations to the “shock” of Turco-Muslim domination resulted in the strengthening of particular tendencies within Indian culture that were already preexistent.

What is indigenous about Indian civilization?

The curry to the right contains potatoes, tomatoes, and chili pepper. All of these are features of Indian cuisine from the last 500 years, as they are New World crops. Unsurprisingly, they were often brought by the Portuguese and spread out from Goa. But, at this point, it’s hard to deny these have been thoroughly indigenized. So this brings me to some questions I have for readers (non-troll answers only, I may start banning people who answer unseriously, since I’m very busy this week and don’t want to waste time with drivel):

The curry to the right contains potatoes, tomatoes, and chili pepper. All of these are features of Indian cuisine from the last 500 years, as they are New World crops. Unsurprisingly, they were often brought by the Portuguese and spread out from Goa. But, at this point, it’s hard to deny these have been thoroughly indigenized. So this brings me to some questions I have for readers (non-troll answers only, I may start banning people who answer unseriously, since I’m very busy this week and don’t want to waste time with drivel):

Continue reading What is indigenous about Indian civilization?

Open Thread – 08/08/2020 – Brown Pundits

I’m traveling with my family a lot this week. Please stay under the control, because if you get out of control I’ll be more kludgey in my response than usual.

Also, to be frank, I would appreciate it if every thread doesn’t devolve into arguments between guys you can imagine whacking off to physical anthropology image plates illustrating racial types from National Geographic in 1930. As they’d say in 1930, everyone beyond Calais is a wog.

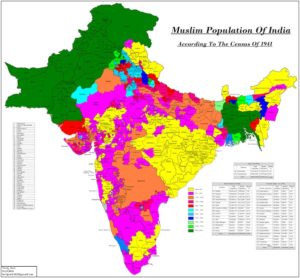

Hindu conversions to Islam in Pakistan

Since many of you are innumerate, I first want to make it clear that Sindh province is 10% Hindu. These Hindus are concentrated mostly in rural areas. As you likely know most elite Sindhi Hindus no longer live in Pakistan. These are poor and relatively powerless people.

This story makes a lot of sense in that context, Poor and Desperate, Pakistani Hindus Accept Islam to Get By:

The mass ceremony was the latest in what is a growing number of such conversions to Pakistan’s majority Muslim faith in recent years — although precise data is scarce. Some of these conversions are voluntary, some not.

News outlets in India, Pakistan’s majority-Hindu neighbor and archrival, were quick to denounce the conversions as forced. But what is happening is more subtle. Desperation, religious and political leaders on both sides of the debate say, has often been the driving force behind their change of religion.

Treated as second-class citizens, the Hindus of Pakistan are often systemically discriminated against in every walk of life — housing, jobs, access to government welfare. While minorities have long been drawn to convert in order to join the majority and escape discrimination and sectarian violence, Hindu community leaders say that the recent uptick in conversions has also been motivated by newfound economic pressures.

As someone who has read a great deal about religious dynamics, this is not subtle, but a very typical. Contrary to some claims, very few conversions to Islam were “forced” in a physical sense. Rather, historically, individuals converted out of self-interest or desperation. Often there were whole communities who make this choice.

A second issue is that there are attempts to present a symmetry between what is happening in India and Pakistan. This story illustrates how no such symmetry exists. Muslims in India are obviously at a disadvantage, but their situation is not analogous to Pakistani religious minorities.

Part of the story here is obviously about the treatment of religious minorities under Islam, which was not out of the ordinary in 1000 A.D., but 1,000 years later is anomalous, insofar as low-grade persecution is common. But it is also a story about the lack of Hindu solidarity with these people who were literally “left behind” as the Lohannas decamped for Mumbai.

Belief and Reclamation

For eons, ascetics and wanderers would journey to the sacred snow-clad Himalayas to test the fires of their belief. Where the skies met the earth and the heavens met the material world, humans met enlightenment; and their discoveries would cascade down the subcontinent. These beliefs would be ossified by ritual and rite, and a culture would engulf the land between the great Himalayas and an endless ocean – India, that is Bhārata.

And it is this legendary journey from the foothills of the Himalayas to the tip of the subcontinent that a civilizational epic takes place – the Rāmāyana. On August 5th, 2020, the ancient song of Valmiki will echo in the villages, in the cities, in the deserts, the fields, the jungles, the mountains, the waters, and especially in the minds of those who believe. A civilization will enact its long-awaited reclamation.

A better commenting system

Readers have been posting stuff about better commenting-systems. I want to keep WordPress because I don’t have time/energy to run a new CMS.

In the comments below put up your suggestions, pros and cons.

I WILL DELETE OFF TOPIC COMMENTS.

Ram temple

Thanks to readers of this weblog I know something is going on with Ayodha in India today. Two stories I read.

First, Slate, a liberal American publications, Why a Giant Hindu Deity Is Appearing in Times Square on Wednesday.

Second, Al Jazeera, India: Modi to lay Ayodhya temple foundation to push Hindu agenda.

I don’t know much beyond superficiality on this topic. Curious about other pieces.