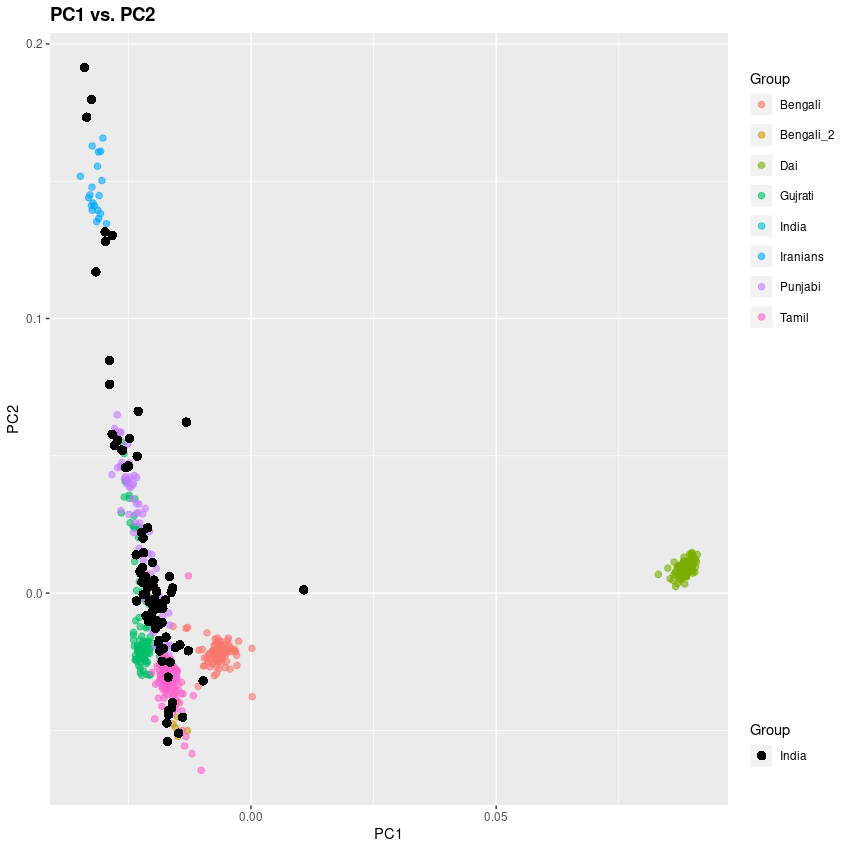

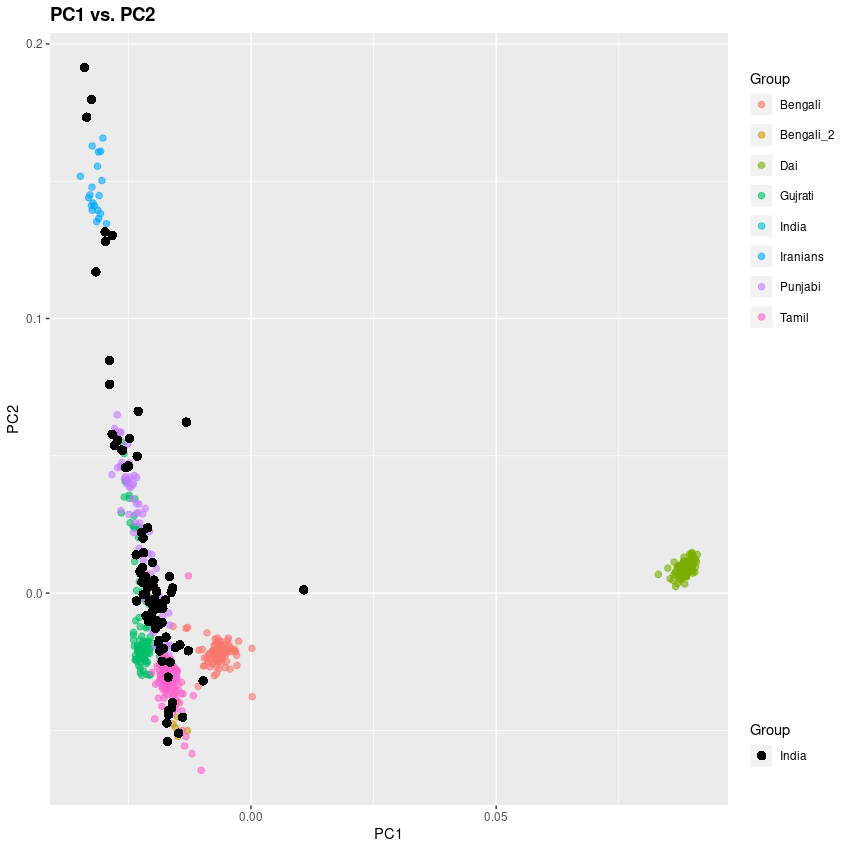

I have a bunch of samples of people who say their four grandparents were born in India from DTC companies. I plotted them on 1000 Genomes with a focus on India. No Southern Dalits in the same for sure.

I have a bunch of samples of people who say their four grandparents were born in India from DTC companies. I plotted them on 1000 Genomes with a focus on India. No Southern Dalits in the same for sure.

What is the difference between introspection and self-hatred? Introspection brings reflection, intention, and evolution. Self-hatred brings rumination, doubt, and rot. One is essential, the other is extinction.

Engagement of either shift one’s fate. From the roots of mentality grow branches of thought, blooming into flowers of action and eventually the fruits of result. Nowhere is this more clear than the night and day of the Indian elite.

The ancient elites of India wrote eternal tomes of meditation that built the bedrock of a civilization that has seen the best and worst of humanity, outlasting every peer and power. Their art and literature emanated confidence, beauty, and advancement. While sure of themselves, they had no qualms integrating new ideas from abroad or from home. Diversity was strength, and challenge was opportunity.

Their descendants today are devolution incarnate – Kali Yuga realized. An unending anguish for the approval of outsiders, self-flagellating of even the most innocent of traditions, and an obsessive compulsion for mediocrity are the trickle-down that these elites have given Indians since independence.

While trivial bashing of them is enjoyable, I want to get to the meat of their minds as well as what these minds have yielded.

What causes the exceptional self-loathing of these elites? The mania of knee-bending and the need to constantly look outwards for validation? The ability to be stupendously arrogant towards their birthright to rule yet despise their roots? Continue reading The Self-Hating Prophecy of Indian Elites

Two BP Podcasts, one after another. You can listen on Libsyn, Apple, Spotify, and Stitcher (and a variety of other platforms). Probably the easiest way to keep up the podcast since we don’t have a regular schedule is to subscribe to one of the links above!

You can also support the podcast as a patron. The primary benefit now is that you get the podcasts considerably earlier than everyone else. This website isn’t about shaking the cup, but I have noticed that the number of patrons plateaued a long time ago.

First, I talk to Karol Karpinski. Karol lived in Dhaka for two years in the mid-2010s. Most of our conversation was around economics since he is an economist, but he also mentions his brush with the tragic events of the Dhaka Isis attack.

Second, to Abhinav Prakash on the farmer protests. Mukunda joins in. Abhinav’s view is that this is basically a rentier class strike.

25% of humans live in the Indian subcontinent. 18.5% live in China. Together that’s 43.5% of the world’s population in the two great Asian civilizations. Not a trivial number in the 21st century, especially in a nascent multipolar world.

25% of humans live in the Indian subcontinent. 18.5% live in China. Together that’s 43.5% of the world’s population in the two great Asian civilizations. Not a trivial number in the 21st century, especially in a nascent multipolar world.

And yet the two societies often lack a deep awareness of each other, as opposed to an almost pathological fixation on the West, and in India’s case the world of Islam.

Indians are clearly geopolitically aware of China. Obsessed even. But aside from cultural exotica (e.g., the Chinese “eat everything”), there seems to be profound ignorance.

This is illustrated most clearly when I hear Indian intellectuals aver the proud continuous paganness of their civilization. Setting aside what “pagan” means, and its applicability to the Hindu religious tradition, the key here is a contrast with the world to the west, which was impacted by a great rupture. The people of Iraq have a written history that goes back 5,000 years, but the continuity between ancient and modern people of the region is culturally minimal. Modern inhabitants of Bagdhad know on some level that their ancestors were Sumerian, but for most of them their identity is wrapped up in their religion and the lives of the Prophet and his family, or for Christians that of Jesus.

This is illustrated most clearly when I hear Indian intellectuals aver the proud continuous paganness of their civilization. Setting aside what “pagan” means, and its applicability to the Hindu religious tradition, the key here is a contrast with the world to the west, which was impacted by a great rupture. The people of Iraq have a written history that goes back 5,000 years, but the continuity between ancient and modern people of the region is culturally minimal. Modern inhabitants of Bagdhad know on some level that their ancestors were Sumerian, but for most of them their identity is wrapped up in their religion and the lives of the Prophet and his family, or for Christians that of Jesus.

This is not the case with the majority of Indian subcontinental people, whose religious traditions and cultural memory go back further, literally to the Bronze Age at the latest. The foundational mythological cycles which define Indian culture probably date to 1000 to 1500 BC. During this time Kassites ruled Babylonia, and the Assyrians were coming into their own. Until modern archaeology, these people were only names in the Bible or in Greek historians.

But this is not only true of India. These Chinese also look to the Bronze Age Shang dynasty, and in particular, the liminal Zhou, to set the terms of their modern culture. The ancient sage kings, who likely predate the Shang, are also held in cultural esteem.

Does any of this matter? I don’t honestly know. I’m American, not India or Chinese. But perhaps it might help on some level if these two civilization-states could understand and accept that they share in common having extremely deep cultural roots apart from the revelation of the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob.

Going to interview Tim Mackintosh-Smith today for the Brown Pundits podcast. He’s the excellent author of Arabs: A 3,000-Year History of Peoples, Tribes, and Empires.

Going to interview Tim Mackintosh-Smith today for the Brown Pundits podcast. He’s the excellent author of Arabs: A 3,000-Year History of Peoples, Tribes, and Empires.

I’ve posted a podcast with Karol Karpinski for patrons. Karol was stationed in Dhaka with the World Bank, and we talk about his experiences (which includes unfortunate proximity to the outbreak of ISIS-related violence in Bangladesh).

Remember the Brown Pundits reddit channel. It’s starting to finally take off. The link is always at the top-right.

The Barua Buddhists of Bengal are often said to be indigenous and continuous practitioners of the Buddhist religion among ethnic Bengalis. That is, they descend from the Buddhist communities of Bengali that flourished during the Pala period, and went into decline during the Muslim period, to disappear on the whole. The claim here is to indigenous status.

The Rohingya, in contrast, often make assertions that they are deeply rooted in Arakan. And, they disavow identification as Bengalis. Their language is clearly closely related to that of Chittagong, and it is not usually written in the Bengali alphabet.

Though I am open to being disproven, over the years in my research on the “Barua”, it seems that in the vast majority of cases these “Bengali Buddhists” descend from Tibeto-Burman people who adopted the Bengali language (or a Bengali-related dialect) and settled in and around Bengalis. They are concentrated in the far Southeast of Bangladesh, and often the boundary between themselves as the Theravada Buddhist Chakma, who retain tribal identity but now mostly speak Bengali, is fluid. The Barua are now Theravada Buddhists, which is the tradition of Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia, and not ancient Bengal.

So basically what I’m saying is this: Buddhist tribal people from the east have assimilated into a Bengali identity, and claimed indigeneity through asserting affiliation with the small Barua ethno-religious group. Meanwhile, in Arakan, peasants who migrated over the last few hundred years from southeast Bengal, have rejected assimilation into the Bengali identity, unified around the standard high culture dialect, and created something distinct.

Woke brown girls with middle class/upper class dads who say they h8 white bois but only date white bois. pic.twitter.com/GelvYxbhcH

— BIMBO_UBERMENSCH (@bimboubermensch) December 3, 2020

Another BP Podcast is up. You can listen on Libsyn, Apple, Spotify, and Stitcher (and a variety of other platforms). Probably the easiest way to keep up the podcast since we don’t have a regular schedule is to subscribe to one of the links above!

You can also support the podcast as a patron. The primary benefit now is that you get the podcasts considerably earlier than everyone else. This website isn’t about shaking the cup, but I have noticed that the number of patrons plateaued a long time ago.

You can also support the podcast as a patron. The primary benefit now is that you get the podcasts considerably earlier than everyone else. This website isn’t about shaking the cup, but I have noticed that the number of patrons plateaued a long time ago.

In this episode, Akshar, Mukunda, and Razib discuss Pakistani and Indian nationalism with Araingang, a well-known Pakistani American nationalist on the internet. We talk about the influence of Sarvakar, the Pakistani focus on West Asia, and the inchoate nature of Pakistani nationalism.

I’m on the road now, so this is prescheduled. Hope Americans had a good Thanksgiving.

For those who are asking, I’m keeping the Patreon because I allocate it to Brown Pundits related costs (hosting podcasts, recording software, etc.). I will be cross-posting some, but not all, podcasts from my paid Substack.

This blog post was triggered by a Twitter exchange with Akshay Alladi where he questioned why I identify with the label liberal. A lot of people have – on this blog as well as on Twitter or in person have labeled me a Hindutva liberal or closet Sanghi (from the left) or a Hindutva rebel, yet I personally don’t feel comfortable with those labels. Maybe it is positive tribalism on the Saffron side or parochial wokism on the left.

Akshay also referred to me in his blogpost about Liberalism vs Conservatism and I promised I would also come up with an elucidation of my position. Before I go into attempts at formulating my position, a fair warning – I am not a particularly deep thinker on matters of philosophy and do not have an intellectual bent. I get bored with long essays and books about philosophy and religion, it’s the interactions of these abstract ideas with politics, people, and histories (as an art/science) that interests me than the ideas themselves.

It is fair to get some personal biases (which may appear contradictory) I hold out of the way

I would like to explain my identification with liberalism in three progressive strains.

Roots and Personality:

The TED talk by Jonathan Heidt is also a good watch on this topic. The presentation points to a study about how liberals rate Harm/Fairness higher than Authority/In group loyalty/ Purity. In those 5 fields, I would firmly identify as a liberal. Yet I am partial to a moral relativistic framework for roots of human morality over morality which claims to be self-evident (Maybe with the exception of the Golden Rule).

I don’t hold purity and especially ritual purity as an important virtue. In general more accepting of things that make me uncomfortable. I am less certain and more flexible in my views and positions. Whether or not this is a liberal quality (or just an outcome of uncertainty and skepticism) is debatable, yet it makes me more open to the opinions I don’t hold or find unpalatable. Additionally Atheism, rejection of traditional wisdom when in the conflict in the Zeitgeist puts one on the liberal side in the liberal-conservative divide in many cases.

However, if it’s the uncertainty that makes me liberal, it’s the cynicism that pulls me slightly on the conservative side. I do not believe that the extremes to which liberal democracies have gone in Europe – wrt Capital punishment, Human rights are either pragmatic or even “humane”.

While the above argument is reasonable, I feel it misses the point that the context and the stage of society one find themselves in, as a determinant of one’s position on the Liberal v Conservative scale. Hence I would go supplement the above moorings with the following context.

Indian society:

Even before my engagement with Politics of Liberalism and Conservatism, I have always intuitively associated with liberalism than conservatism. Being a radical atheist, a guilt-ridden savarna and a wannabe feminist has meant that in my family and friend circle I was always the most “Progressive” voice – of course, this is in comparison to more conservative voices.

While there are many things in Indian society worth conserving, it’s the adverse effects of these very things that bother me. The idyllic Indian village is home to both the best and the worst that Indian culture has to offer. One of the good things being the social safety net offered by caste and kin connections and the worst being the rigid institution of caste and sexism which is rampant in such settings. For example – I would not wish to conserve the Indian Joint family – in my worldview that structure has more cons than pros in the 21st-century world we live in. And more importantly, these caste and kin networks are anathema to individual rights and freedoms. If the concepts of personal space and privacy are considered important, one of the ways to achieve this would be loosening the bonds of caste and kin networks.

As Indian society currently stands on balance I would want the society as a whole to progress even if it means sacrificing some things that are good on their own. The conservative position here would be to encourage focusing on conserving traditions while interacting with modernity. The debate between Tilak and Agarkar, Gandhi, and Ambedkar are wonderful examples of such strife in our history, and I would in both cases firmly identify with Agarkar/ Ambedkar’s position. (Though I admire Tilak and Gandhi).

As alluded to in my post on Brahmanical Patriarchy. I personally abhor the traditional treatment of women by religion. In the comment thread, Srikanta K noted the slippery slope that leads from critiques of Brahmanism from Women’s’ rights POV, could lead to the destruction of tradition or demonization of brahmins. My position is exactly the opposite, I focus on the same issue with a different slippery slope, the one which our societies have actually witnessed in history. I can jettison traditions when they conflict with my morality or worldview – even these very traditions may have a net positive impact on society.

However, this position depends vastly on the current state of Indian society I find myself in. From what I know of British and Western societies – I would be markedly less “liberal” if I were in those societies. In other words, I might want to conserve the society the west was a few years ago instead of wanting an identity-focused woke revolution.

Indian Politics and Personalities (Litmus tests):

Complimentary to this would be how one related to national politics, issues, and personalities. A year ago I read the Gita Press and the Making of Hindu India. It is not only a fascinating window into the extraordinary life of Hanuman Prasad Poddar but also a compilation of how Indian leaders responded to the writings, thoughts, and work of Gita Press and Poddar. Gandhi, Rajendra Prasad, Sardar Patel, and even Lal Bahadur Shashtri (along with numerous others) are referenced in the book as having a positive outlook towards the Gita press initiative and reciprocally the Gita press was positive towards these individuals. Conspicuous by their absence are Nehru and Savarkar, while Ambedkar is given somewhat harsh treatment by Gita Press – especially the magazine Kalyan. Incidentally, the three Indian thinkers whose thoughts I relate to most are Nehru, Ambedkar, and Savarkar. While this is a weird group to look up to, but the modernist and rationalist (may I say Liberal ?) zeal in all these individuals that most appeals to me today. The fusion of these thinkers might create a good ideological role model in my thoughts. Personally, I would be most at home with a political outfit that takes Nehru’s liberalism with a pinch of Savarkar’s reformist and nationalist zeal while sticking to the constitutional democracy based on a hotch-potch of western models that Ambedkar held dear and all the while being particularly skeptical of Islam as a religion.

While I don’t deny that India is an ancient civilization (Dharmic for a lack of a better term), in its current Avatar, India is a nation-state of the Westphalian model, and though there may be flaws in this model IMO this model is vastly superior to all previous models known to this land or any land for that matter. Not to go all Niall Ferguson here, but I am partial to the view that the rise of the Western civilization is not just correlated with Western models of governance and economy (classical liberalism) but a consequence of it.

Another way to look at this question could be like a Y/N Test on current issues. Some current polarizing issues and my stance on them as follows:

On balance, based on the above issues, my position would be firmly liberal on the liberal vs conservative scale. This is not an accurate assessment in a broad sense, but a consolidation of the above thoughts in a much-needed context. Without context, these labels are mere abstractions, and hence not very useful and not necessarily transferable in a different context. In a state with a just and efficient rule of law, I would probably not identify with liberalism as much, for, in such a state, the tools and mechanisms for the needed change in society can be achieved more easily. But I am not living in such a state and hence would be firmly a Liberal.

Postscript :

I would not be very liberal with comments that arent constructive and civil.