Since the Ram Janmabhoomi movement, which culminated in the demolition of the Babri Masjid, nothing has polarized Indian politics and society as much the Citizenship Amendment Act. On its own, its fair to assume that CAA is not a particularly insidious piece of legislature, but when it gets combined with National Register of Citizens (NRC) as explained by Amit Shah below, it becomes some to be vary of.

As Amit Shah stated, CAB(A) will be applied before carrying out the process of NRC. In his own words, the refugees(non Muslim migrants) will be granted citizenship and the infiltrators (Muslim migrants – he also referred to them as termites at one instance) will be thrown out or prosecuted (there was some talk of throwing them into the Bay of Bengal).

Its clear to conclude that by refugees – he means Bangladeshi Muslims who reside illegally in India as almost no Muslims from Pakistan and Afghanistan come to India illegally with an intention a better life. (When they do cross the LOC illegally, they’re treated as enemy combatants or terrorists)

The ACT:

The instrumental part of the act reads

any person belonging to Hindu, Sikh, Buddhist, Jain, Parsi or Christian community from Afghanistan, Bangladesh or Pakistan, who entered into India on or before the 31st day of December, 2014 and who has been exempted by the Central Government by or under clause (c) of sub-section (2) of section 3 of the Passport (Entry into India) Act, 1920 or from the application of the provisions of the Foreigners Act, 1946 or any rule or order made thereunder, shall not be treated as illegal migrant for the purposes of this Act

While this amendment to the ACT is seen as problematic, one must point out that large portions of the existing ACT are also extremely problematic – most of which were added after 1955 under various governments at various times. In particular the 1986 amendment (under Rajiv Gandhi) – which meant children born to both illegal immigrants wouldn’t get citizenship. This is seen as a contradiction with the Birthright naturalization (Jus soli ) principle of the Constitution. The 2003 amendment (under Vajpayee) further restricted citizenship to children, when either of their parents is an illegal immigrant.

The 2003 amendment also prevented illegal immigrants from claiming naturalization by some other legal means. So in short with the CAA 2019, this particular amendment (2003) has been annulled for Non Muslims who have come to Indian sovereign land from Bangladesh, Pakistan and Afghanistan.

In other words, the CAA facilitates the imagination of India as the natural homeland of subcontinental Non-Muslims (but not a Hindu Rashtra or Hindu State).

Objective Reasons for opposing the CAA:

Continue reading Citizenship Amendment Act – the straw that broke the camel’s back

Since about 2006 I’ve had to write the same post again and again due to the nature of my audience: religion is not the purview of technically oriented nerds, and technically oriented nerds just don’t “get” it intuitively. This is something that is relevant to me personally, because I am myself a technically oriented nerd, and I just don’t “get” religion.

Since about 2006 I’ve had to write the same post again and again due to the nature of my audience: religion is not the purview of technically oriented nerds, and technically oriented nerds just don’t “get” it intuitively. This is something that is relevant to me personally, because I am myself a technically oriented nerd, and I just don’t “get” religion.

Between 1995 and 2005 I went through a “Richard Dawkins” phase. As it happens, I met Dawkins casually in 1995 at a talk and had been reading his biology works. I was not particularly interested in his religious commentary. Rather, I read books such as

Between 1995 and 2005 I went through a “Richard Dawkins” phase. As it happens, I met Dawkins casually in 1995 at a talk and had been reading his biology works. I was not particularly interested in his religious commentary. Rather, I read books such as

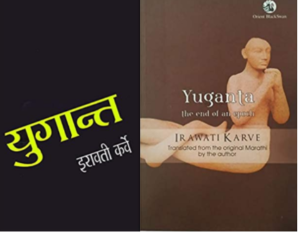

Yugant confronts various versions of Mahabharat analytically and tries to make sense of character arcs and motivations. Intelligently analyzed without religious respect but with literary respect. The motivations of Pandavas for marrying Draupadi as the Royal Queen are very well explained. The literary accounts of chats between Dhritarashtra and Gandhari & those of Draupadi’s death are very well written and move your heart. Krishna (Vasudeva) stands out not only because of the brilliance of his character but the wonderful analysis and the crisp unraveling of his motivations. The Arya (Kshatriya) Dharma is explained in Krishna and Yugant chapters. The author enthralls with deep and intelligent writing in the final chapter that resonates wonderfully even in the 21st-century internet age. The sincere and irreligious comparisons of Mahabharat Era – Arya Dharma to contemporary Hindu religion and other Prophetic Faiths are interesting. Throughout the book, the author refrains from applying current Zeitgeist as a yardstick – something which is refreshing in 21st century polarized analysis and debates which always have political undertones. Even without a direct running story arc – the arrangement of essays offers a wonderful climax – especially Krishna and Yugant chapters. With recent elevation of Heroic Karna in Indian literature and thought, a look back of the character of Karna as seen in 1950s-60s is a pleasant change.

Yugant confronts various versions of Mahabharat analytically and tries to make sense of character arcs and motivations. Intelligently analyzed without religious respect but with literary respect. The motivations of Pandavas for marrying Draupadi as the Royal Queen are very well explained. The literary accounts of chats between Dhritarashtra and Gandhari & those of Draupadi’s death are very well written and move your heart. Krishna (Vasudeva) stands out not only because of the brilliance of his character but the wonderful analysis and the crisp unraveling of his motivations. The Arya (Kshatriya) Dharma is explained in Krishna and Yugant chapters. The author enthralls with deep and intelligent writing in the final chapter that resonates wonderfully even in the 21st-century internet age. The sincere and irreligious comparisons of Mahabharat Era – Arya Dharma to contemporary Hindu religion and other Prophetic Faiths are interesting. Throughout the book, the author refrains from applying current Zeitgeist as a yardstick – something which is refreshing in 21st century polarized analysis and debates which always have political undertones. Even without a direct running story arc – the arrangement of essays offers a wonderful climax – especially Krishna and Yugant chapters. With recent elevation of Heroic Karna in Indian literature and thought, a look back of the character of Karna as seen in 1950s-60s is a pleasant change.