At my other blog, The Decline Of Genocide And The Rise Of Rents. One of the comments is from someone with an Indian name:

The problem with the whitewashing of the islamic invasions of India is that first, nobody does that with the christian invasions of sub saharan Africa and even more so, central and South America and secondly, the genocides did not stop in the past.

I wonder how much of what the author wrote applied to the European conquests of central and south america where the aim was clearly to slaughter and convert.

Since the commenter is parochial, they don’t know about the Spanish Black Legend, which was an Anglo-Protestant propaganda effort to argue that the Catholic Spaniards were particularly cruel and evil. The reality is that the aim was to convert, but, it was also to turn the indigenous peasantry into sources of rents for the Spaniards, who were keen on living like aristocrats in the New World. The demographic collapse of the indigenous population prevented some of that and necessitated the importation of African slaves.

Since the commenter is parochial, they don’t know about the Spanish Black Legend, which was an Anglo-Protestant propaganda effort to argue that the Catholic Spaniards were particularly cruel and evil. The reality is that the aim was to convert, but, it was also to turn the indigenous peasantry into sources of rents for the Spaniards, who were keen on living like aristocrats in the New World. The demographic collapse of the indigenous population prevented some of that and necessitated the importation of African slaves.

Why was there a demographic collapse? It wasn’t really the Spaniards killing the native people in large numbers (in fact, the conquest of America occurred with the large-scale cooperation of indigenous allies). Rather, it was disease, as outlined in Charles C. Mann’s 1491. If you look at the comment about, you will notice a peculiar contradiction in the idea that one would want to “slaughter and convert.” Winning souls usually entails keeping them alive!

Henry Kamen’s Empire: How Spain Became a World Power, 1492-1763, the author outlines the contrasting case of what has become the Phillippines. Here Spaniards and mestizos were a tiny minority, and the indigenous peoples were the overwhelming majority, with a large number of Chinese engaging in trade. Why the difference? Because the Spaniards did not bring disease that were particularly impactful on the people of the Phillippines, and on the contrary, tropical climates in Asia were not healthful for Europeans. The mortality rate for the Dutch East India Company in Batavia was incredibly high, as Southeast Asia served as a great mortality maw for young men from the Netherlands and Germany for generations.

Henry Kamen’s Empire: How Spain Became a World Power, 1492-1763, the author outlines the contrasting case of what has become the Phillippines. Here Spaniards and mestizos were a tiny minority, and the indigenous peoples were the overwhelming majority, with a large number of Chinese engaging in trade. Why the difference? Because the Spaniards did not bring disease that were particularly impactful on the people of the Phillippines, and on the contrary, tropical climates in Asia were not healthful for Europeans. The mortality rate for the Dutch East India Company in Batavia was incredibly high, as Southeast Asia served as a great mortality maw for young men from the Netherlands and Germany for generations.

The contrast with Africa is the most extreme. Fatal disease meant that the European presence in Sub-Saharan Africa was constrained to isolated fortifications and trading center on the coast for centuries. The reason Africa was “dark” was that even after all this time much of it was unexplored into the 19th century. If you look at biographies of the “Arab slave traders” from this period you will observe that many were of predominant black African ancestry. The primary, but not exclusive, reason for this difficulty of conquest and domination was malaria. The introduction of quinine opened up the continent to Europeans and resulted in the scramble for Africa.

Though some European missionaries did come to continent with colonialism, in most places mass Christianization occurred after the end of European rule. It was driven by native Christians and often spread fastest among groups that were located adjacent to Muslims. Christianity was seen as a bulwark of the native culture against Islam,* which Vodun and other indigenous beliefs exhibited little resistance (it is a peculiar fact that “public paganism” persists in West Africa, but not in East Africa, where tribal religions are much more rural and marginal phenomenon).

What can this tell us about India? As I have posted at length, it testifies to the power and strength of native Indian religious ideas and systems. Though Hindus say they are “pagan”, they are not pagan like African pagans. Or pagans like the people of highland Southeast Asia, or the New World. Or Classical Antiquity. Muslim rulers dominated the region around Delhi from 1200 to 1770, but 80-90% of the people in the region remained non-Muslim at the end of this period!

And yet 30% of subcontinental people are now Muslim. They are concentrated on the margins, in the far west and far east. What does this tell us?

A standard model presented is that slaughter and mass-killings resulted in the shift of religion at the point of the sword. Were Muslims particularly brutal in the west and the east? More brutal in eastern Bengal than western Bengal? More brutal in southeast East Bengal than northern East Bengal?

The idea of an exceptionally violent and brutal occupation is promoted and encouraged by many factors. First, many Muslims in the past and even actually like the idea that the Turks and Mughals were particularly vicious and zealous. The Turks themselves had an interest in portraying themselves as such ghazis converting pagans at the point of the sword. For Hindus, the conversion of marginal, liminal, and low caste communities to Islam of their own free will is not something one would want to address, because it points to “push” factors within Hindu society. Defection says something about the group from which you defect.

Finally, there is the reality that the Muslims did engage in forms of cultural genocide. The destruction of temples, the selective targeting of the religious, the imposition of an alien Persian high culture, are all true things that occurred in a Hindu India.

Note: I may just delete a lot of comments on this post if they don’t meet my standard. Just warning.

* The attraction of highland Southeast Asians to Christianity has the same tendency: they see it as a bulwark against absorption into lowland Buddhist culture.

Recently on Twitter someone asked why people of subcontinental backgrounds who leave Islam don’t refamiliarize themselves with the religion of their ancestors. One response could be “well actually, my ancestors weren’t really Hindu…” I think this is a pedantic dodge. In places like Iraqi Kurdistan and Tajikstan some people from Muslim backgrounds are embracing a Zoroastrian identity.

Recently on Twitter someone asked why people of subcontinental backgrounds who leave Islam don’t refamiliarize themselves with the religion of their ancestors. One response could be “well actually, my ancestors weren’t really Hindu…” I think this is a pedantic dodge. In places like Iraqi Kurdistan and Tajikstan some people from Muslim backgrounds are embracing a Zoroastrian identity.

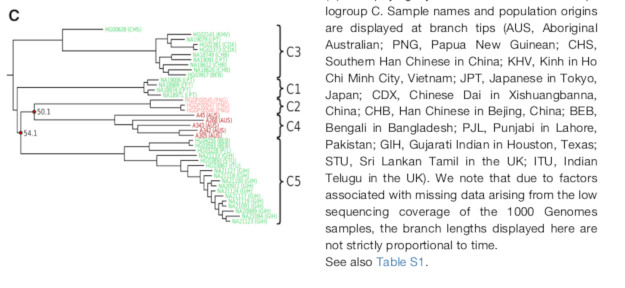

They asked for my opinion. I agree with many of the aspects of the piece. There is something of an attempt, in my opinion, to downplay the coercion and violence that were part of the expansion of many Y chromosomal lineages, groups of males, ~4,000 years ago. In fact, the author of the above piece probably overestimates the fraction of Aryan mtDNA in India; most West Eurasian lineages in South Asia are probably from West Asian, not the Sintashta.

They asked for my opinion. I agree with many of the aspects of the piece. There is something of an attempt, in my opinion, to downplay the coercion and violence that were part of the expansion of many Y chromosomal lineages, groups of males, ~4,000 years ago. In fact, the author of the above piece probably overestimates the fraction of Aryan mtDNA in India; most West Eurasian lineages in South Asia are probably from West Asian, not the Sintashta.