Disclaimer

Please note I am a dentist — not a geneticist — and I do not claim formal expertise in this field. I have a long-standing interest in history and look to archaeogenetics as one of the best tools available for addressing some of the most enduring questions about South Asian origins and identity.

Credit is due to the many researchers, bloggers, and science communicators who have made this field accessible — including Razib Khan (whom I haven’t met, though he happens to be a fellow Bengali), who’s writing first inspired me to engage deeply with these questions.

I first got into Ancient Indian DNA space when the research from the Rakhigarhi woman’s DNA was published- shedding light on IVC genetics for the first time. Prior to that Indian society had no idea how to scientifically answer questions like whether the “Aryan-Invasion” was real. Everything you heard or read was just some dude’s opinion.

If the Aryan invasion was real didn’t the Indus Valley civilization prove the indigenous but conquered “Dravidians” were the ‘superior’ culture builders and the Aryans were the barbarians?

If they spoke Dravidian languages, did it mean they looked South Indian… and that after the invasion they were all somehow transplanted into the actual South of the peninsula – while the Indus region was taken over by… White people??

These were the conundrums that filled my mind and it was due to the work of some of these excellent pioneers in the genetics field (Shinde, Narasimhan, Reich and Razib) that I went down the rabbit hole of answers.

At some point as more research came out about the Indus people and the genetics of the caste system, there seemed to sprout the idea dimly apparent but visible if you looked – that Dravidians themselves as a language group may not be native to India.

Now I wasn’t completely sold. Like many of you I wonder why it can’t be the other way around.

Why did neolithic Iranians have to come into India – why can’t it be that neolithic northwest Indians went to the Iranian plateau? I don’t have all the answers, and it’ll take a while for all the questions to be settled. Till then I try to keep my biases in check and follow the research.

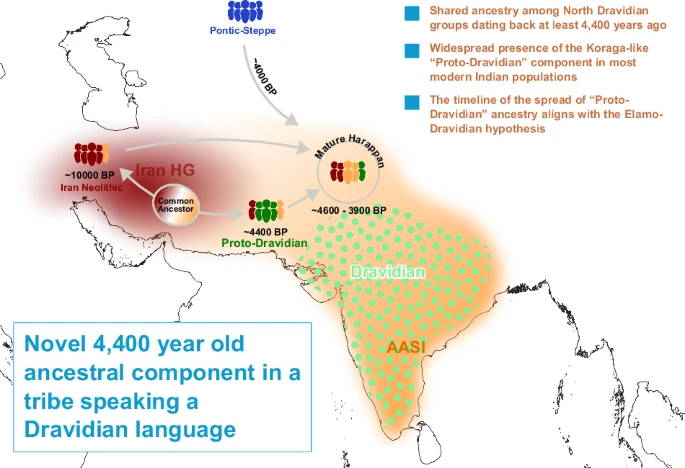

A paper came out in Nature in October shedding light on the possible genetic basis to the origins of the Dravidian language family.

The researchers sampled a small tribe – the Koraga from Southern India speaking a Dravidian language.

Now we all know the main cline of Indians come from Steppe, Indus farmer and AASI in the literature.

New finding from this paper: Proposed fourth ancestral component — which they call “Proto-Dravidian” ancestry — found in the Koraga, which branched off around 2,400 B.C.

The origin of this ancestry seems to lie in the region between the Iranian plateau and the Indus Valley before the arrival of Indo-European languages. It persists in diluted form in many South Asian communities (not just in the tribal population) today, especially Dravidian speaking ones.

The researcher purport this may provide support to the Elamo-Dravidian language family hypothesis, which would provide a common source of languages for all populations derived from Neolithic Iranians back to one of the centres (Zagros) where farming was invented.

What does this research imply about the ancestry of the IVC people and what language they spoke?

What does it imply about the so-called “Indus farmer” component of Indian ancestry?

The Indus farmer as one of the three key sources of Indian ancestry was thought to represent the core ancestry of the IVC.

This study with the Koraga finds a distinct 4,400-year-old branch of the main Neolithic Iranian and not identical to the core “Indus Farmer”. Genetically it’s closer to current Dravidian speaking rather than Indo-Aryan speaking populations.

There might have been two (or multiple) Iranian-related influxes into the subcontinent:

- An earlier, associated with Neolithic spread of agriculture (≈ 7000–5000 BCE → the IVC base population),

- at least one later sub-branch (~2400 BCE) that corresponds to this “Proto-Dravidian” ancestry.

So, the IVC population may have contained multiple Iranian-related sub-lineages, one of which could have seeded the Proto-Dravidian gene pool that persisted in southern India.

The 4,400-year-old date inferred for the Proto-Dravidian ancestry roughly matches the mature-to-late IVC period (2600–1900 BCE).

While genetics can’t “prove” a language, the chronological and geographical overlap adds circumstantial weight to the idea that the language(s) of the IVC were Dravidian or Proto-Dravidian in nature.

Wasn’t the mature period of the IVC already in full swing 4,400 years ago?

The Indus Civilization wasn’t a single static population—it extended from Baluchistan and Sindh up to Haryana and Gujarat, and its regional sub-populations may have had slightly different genetic mixtures.

Local differentiations could easily occur within that 700-year mature phase.

So the “Koraga-like” branch could represent:

- a southern or interior offshoot of the broader IVC population, or

- the southernmost fraction of IVC peoples who moved into peninsular India as the civilization urban centres declined (post-1900 BCE).

What does it suggest about Brahui or Burushaski or Nihali languages; the three “mystery” languages?

Brahui – the case is strengthened for this language to be a relict of an IVC-era language and not a recent back migration from South to North. These speakers genetically have the same ancestral components of the Indo-Aryan speakers around them rather than the amplified “proto-Dravidian” component that you would expect from migrants from the South.

Burushashki – Fits a scenario where it could descend from a pre-Indo-Aryan, pre-Dravidian language of the upper Indus region — maybe a branch of the same broad macro-family that included IVC languages.

– may preserve a northern dialect of the IVC-era linguistic landscape — an (adopted) sister, not daughter, to Proto-Dravidian which survived in a mountain redoubt while Indo-Aryan took over the plains.

Nihali – may descend from one of these pre-Munda, pre-Dravidian forager populations, preserving fragments of a Mesolithic or Neolithic substratum language.

This fits with the new study’s timeline:

- the IVC-Dravidian connection crystallized after 2600 BCE,

- but eastern and central India already had long-established hunter-gatherer cultures with minimal Iranian-farmer input.

Nihali probably represents a pre-agricultural linguistic substrate, not Dravidian or IVC-derived at all — more of an AASI linguistic survivor.

The roots of what became Jati

I won’t go too in depth as the field here is still a lot of theory without definitive answers – this paper taken with Narasimhan (2019) and Shinde (2019) finds that at least 4,400 years ago IVC was already a genetically distinct and relatively stable mix of Iran-related farmer ancestry + South Asian forager ancestry, with internal substructure.

- Significant regional genetic variation between different Indus sites

- Long-term persistence of ancestry profiles — meaning mixing across the entire IVC zone was not completely random.

Does that mean “caste”?

Not strictly in the Vedic sense with Varna, Jati as far as we can see but it could mean that:

- There were endogamous or semi-endogamous groups within the IVC.

- These groups likely corresponded to occupational, regional, or lineage divisions, rather than religious varnas.

- The cultural habit of limiting marriage circles could therefore be much older than the Indo-Aryan social codes that later memorialized it as varna–jati.

- The original social boundaries may be linked to pre-agriculture tribal or kinship identities that were maintained even throughout the period of early urbanization/integration.

We know from the paper: 50,000 years of evolutionary history of India: Impact on health and disease variation – India has long been a reservoir for human DNA.

Old groups are preserved alongside but separate from the new… far longer than other subcontinents where homogenization cause their disappearance.

This was true for archaic hominins living in India before Out of Africa (according to the archaeological record) and continued to be true afterward even through to the coming together of these different groups as they built the first cities.

————————————————–

This paper does not settle the origins of the Dravidian languages or linguistic identity of the IVC.

It’s my first article so if people want to share feedback – please feel free and keep it respectful – thanks. If there is interest I have more ideas planned like the history of endogamy in South Asia and the intersection across culture, politics and identity from the perspective of a second generation Indian (West Bengal) Australian.

Warm Regards,

Dr Rajorshi

welcome.

To me, there is more than a bit of… “reading tea leaves” aspect to all this theorizing. Is it inaccurate to point out that this type of ‘proto-Dravidian’ hypothesizing ultimately is based on, bottomline, small sample-sets, and the conclusions are essentially speculative?

Hi,

The first study on this topic was released in 2024 ,

Look up : Human Y chromosome haplogroup L1-M22 traces Neolithic expansion in West Asia and supports the Elamite and Dravidian connection.

Their trace is in the diagram. For me it isn’t settled either but too many pieces falling into place to ignore.

On the Indian side more research to parse out movements and history of AASI populations is on its way.

Fine article;

We had mentioned something like this on the IVC podcast 2-3 years ago.

IVC clearly was multi-lingual – and the signs/script may be encoding a common link language of sort.

So in a sense – South Indians who appear enriched in IVC may actually have this Proto Dravidian ancestry and not the IVC ancestry seen in North and east. Subtler changes like these can only be found with Ancient DNA from Daimabad Jorwe cultures or from further south in Vaigai – or ancient southern Neolithic.

Very likely that mature IVC began expanding southword and the link was broken with end of Integration phase {Mature harappan}; 2000 BCE onwards also maps as a good time for diversification of modern Dravidian languages – Telugu branch and Tamil branch along with other branches

Keeladi (or Keezhadi as Tamil spell it)

“We have found graffiti in the Tamil Brahmi script dating back to the 6th Century BCE, which shows that it is older than the Ashokan Brahmi script. We believe that both scripts developed independently and, perhaps, emerged from the Indus Valley script,” Mr Kumar says.

https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cwyq443xypjo

Keeladi (or Keezhadi as Tamil spell it)

“We have found graffiti in the Tamil Brahmi script dating back to the 6th Century BCE, which shows that it is older than the Ashokan Brahmi script. We believe that both scripts developed independently and, perhaps, emerged from the Indus Valley script,” Mr Kumar says.

https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cwyq443xypjo

Keeladi (or Keezhadi as Tamil spell it)

“We have found graffiti in the Tamil Brahmi script dating back to the 6th Century BCE, which shows that it is older than the Ashokan Brahmi script. We believe that both scripts developed independently and, perhaps, emerged from the Indus Valley script,” Mr Kumar says.

A BBC article

I’ve heard this theory. One of two as I understand –

Most scholars accept the first theory though… who knows what we discover in the next 5 years of archeology!

There is rock art in SL very much like Harrappa line art.

First cave

Seven animal figures and seven human figures and many geometric shapes on the inner walls. The human face behind the animal is unique, with both hands on it and the face to the left.

The gray line draws a picture of a deer painted in the center red color.

A human figure with a running posture drew from the white line, a left-handed human figure with a bow, an animal-drawn from the gray line, and a human figure with two behind

Hi Gaurav,

Yes I’ve heard the podcast episode on IVC. I considered it to be “assumed knowledge” for people who would read this article. New information has been sparse on the archaeogenetics of the Indian people and the IVC but now things are moving along.

Would even be happy to contribute to future podcast episodes on the topic.

“So in a sense – South Indians who appear enriched in IVC may actually have this Proto Dravidian ancestry and not the IVC ancestry seen in North and east.” I would interpret that they still have IVC ancestry as seen in North and East and vice versa for North & East to have Koruba (hypothesized) Proto Dravidian genetics but its probably proportions are different between regions.

More research needs to be done on the different regional groups of the IVC to be sure. And the Jorwe, as you pointed out. And the Jiroft culture in the eastern Iranian plateau.

And to your last point – yes it absolutely makes sense that the brisk maritime trade existing between IVC and Mesopotamia incrementally spread down the West Coast of India. Another excellent point where I would like to see further studies done.

and not the IVC ancestry seen in North and east.

IVC seems to have been black people (no hard evidence of other shades), Have you seen the Dancing Girl statue of Mohanda-Jaro now in a museum in Pakistan

AASI mtDNA genomes from Sri Lanka (2500 and 5500 BC)

Mesolithic hunter-gatherers from two cave sites. The mitochondrial haplogroups of pre-historic individuals were M18a and M35a. Pre-historic mitochondrial lineage M18a was found at a low prevalence among Sinhalese, Sri Lankan Tamils, and Sri Lankan Indian Tamil in the Sri Lankan population, whereas M35a lineage was observed across all Sri Lankan populations with a comparatively higher frequency among the Sinhalese.

No links as comment goes to admin