“The southern Indians resemble the Ethiopians a good deal, and, are black of countenance, and their hair black also, only they are not as snub-nosed or so woolly-haired as the Ethiopians; but the northern Indians are most like the Egyptians in appearance.”

– Arrian

I might almost say that the same animals are to be found in India as in Aethiopia and Egypt, and that the Indian rivers have all the other river animals except the hippopotamus, although Onesicritus says that the hippopotamus is also to be found in India. As for the people of India, those in the south are like the Aethiopians in colour, although they are like the rest in respect to countenance and hair (for on account of the humidity of the air their hair does not curl), whereas those in the north are like the Egyptians.

-Strabo

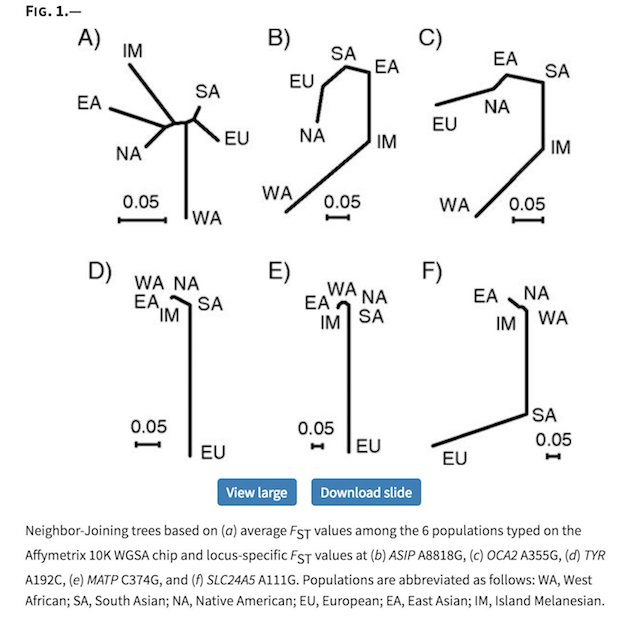

The plot above is from Genetic Evidence for the Convergent Evolution of Light Skin in Europeans and East Asians. It’s a 2007 paper. For those of you not versed in genetics, 10 years is like the difference between the First Age and Third Age on Middle Earth. For those of you not versed in Tolkien, 10 years is like the difference between Gupta India and Maratha India? I think?

Basically, the authors looked around the regions of the genome of loci known to be implicated in pigmentation variation in 2007, which mostly started from differences between Europeans and Africans. In the plot above you see pairwise genetic distances visualized in a neighbor-joining tree. The populations are:

SA = Asians, IM = Island Melanesians, WA = West Africans, EU = Europeans, EA = East Asians, and NA = Native Americans

What you see is that pigmentation loci are not phylogenetically very informative. Because of ascertainment bias in discovery Europeans are an out-group on many of the genes. But overall you see that the trees generated by a relationship on pigmentation genes do not conform to what we’d expect, where Africans are an outgroup to non-Africans. This is not surprising, as any given locus is not too phylogenetically informative. Additionally, pigmentation is a trait where selection has likely changed allele frequencies a lot, so it’s not a very good trait to look at to determine evolutionary relationships.

I bring this up because The New York Times and other publications are reporting on a new paper in Science, Loci associated with skin pigmentation identified in African populations, with headlines like Genes for Skin Color Rebut Dated Notions of Race, Researchers Say.

The Science paper is very interesting because it helps to make up for the long-term ascertainment bias in the literature, whereby European differences from other groups helped to discover pigmentation loci of interest. The big topline result is that there’s a lot of extant variation within Africans, and much of it is very old, pre-dating modern humans by hundreds of thousands of years, implying long-term balancing selection to maintain polymorphism.

Here’s a quote from The New York Times piece:

For centuries, skin color has held powerful social meaning — a defining characteristic of race, and a starting point for racism.

“If you ask somebody on the street, ‘What are the main differences between races?,’ they’re going to say skin color,” said Sarah A. Tishkoff, a geneticist at the University of Pennsylvania.

…The widespread distribution of these genes and their persistence over millenniums show that the old color lines are essentially meaningless, the scientists said. The research “dispels a biological concept of race,” Dr. Tishkoff said.

I can go along with all the sentences more or less except the last. Skin is the largest organ we have, and it’s pretty salient. West Asian Muslims regularly referred to Indians as “black” (early Islamic Arabs referred to the people of Sindh as “black crows”). They defined themselves as white (though contrasted their own olive complexion with ruddy Europeans). The Chinese referred to themselves as white, and Southeast Asians, such as the inhabitants of the ancient Cambodian kingdom of Funan, as black. Among South Asians, skin color is also very salient. During the period when Pakistan included a western and eastern half the West Pakistanis were known to refer to the Bengalis as blacks, while East Pakistanis who went to study in the West, like my father, were surprised that not all Pakistanis were white like Ayub Khan.

But racial perception and categorization are not identical with skin color. The ancients knew this intuitively, as the quotes from Arrian and Strabo above suggest. They were aware that South Asians were dark-skinned, but those in the north were lighter than those in the south, and that those in the south resembled Africans in the range of their complexion. But, they also knew that it was not difficult to distinguish a South Asian from an African in most cases, because South Asians have different hair forms and to some extent facial features, from Africans.

I know this myself personally. Living in almost white areas of the United States for most of my childhood I encountered some racism. My skin tone is within the range of African Americans. But when it came to racial slurs I was usually called “sand nigger”, or more sometimes “camel jockey.” Please note that the modifier sand. Even racists understood to distinguish people of similar hues who were clearly physically distinctive.

Conversely, African Americans did not usually recognize me as African American. Living in the Pacific Northwest there aren’t many non-whites. It’s also very rainy. Sometimes when I was wearing my Columbia jacket with hood black men walking from the other direction on the sidewalk would start to nod at me, assuming I was black. But mid-way through the nod as they approached me they recognized that despite my brown color I was not African American and would stop the motion and switch to a manner of distanced politeness as opposed to informal warmth.*

Finally, I also had East Asian friends who were very light-skinned. As light-skinned as any white person of Southern European heritage. That did not prevent racists from calling them “chinks” or (more rarely) “gooks.” These racists were seeing beyond the skin color.

If ancient authors from 2,000 years ago understood that race is more than skin color, and if genuine bigots understand race is more than skin color, I fail to understand why so often the public discourse in the United States acts as if race is just skin color. We know it’s not so.

The reason I’m posting this on Brown Pundits is that the focus on skin color made sense to me growing up in the United States, but as someone of South Asian ancestry I also knew it was not sufficient as a classifier. I knew when I was probably around five. Many South Asians see a huge range in skin color within their immediate families. That is, empirically the fact that there were large effect QTLs segregating within South Asians is obvious to any South Asian who grew up around South Asians.**

My mother is of light brown complexion. My father is of dark brown complexion. My mother’s complexion is fair enough that she is usually assumed to be Latina if she doesn’t speak (her accent is clearly South Asian), and in cases has been misjudged to be Southern European. My father, like his mother, is in contrast on the darker side. Their Bengali friends would joke that they were an interracial relationship.

My father’s father was very light skinned, and his mother was very dark skinned. Some of his siblings were dark, some of them were light, and some of them were between. One of my father’s brothers is basically a doppelganger of my father, except he is lighter skinned.

And yet there was never a question that both my parents were ethnically Bengali. They were both people with deep roots in Comilla in eastern Bengal. Now that I have their genotypes I can tell you that my parents are genetically clearly from the same region of Bengal; they cluster together even compared to other Bangladeshis. In fact, my father is more Indo-Aryan (every so slightly) shifted than my mother. I suspect it is through his mother, whose father was born into a family of recently converted Brahmins. It is clear that skin color is not predicting phylogeny in this case, and I am sure many South Asians intuitively grasp this because of the variation in complexion they see across their families, who are usually from the same sub-ethnic group in any case.***

A multiracial United States is going to be more complex world than the situation before 1965, when America’s racial consciousness was partitioned between black and white (notwithstanding Native Americans, Hispanos and other Latinos in the Southwest, and a residual of Asian Americans). But sometimes I feel the intellectual and cultural elite of this nation is stuck in the paradigm of 1964.

* I have a friend from Kerala in South India who has talked about being mistaken for being Ethiopian.

** I am the only South Asian my daughter has grown up around, and her complexion is far closer to her mother’s than my own. She did have a difficult time distinguishing me from black males in her early years because to her my dark-skin is very salient. When her mother asked her to give reasons why African American males might look different from her father, she immediately clued in on the hair and facial features.

*** Black Americans and Middle Easterners, and a whole host of other groups where pigmentation loci segregation in appreciable frequencies, can all see that differences in skin color do not necessarily denote differences in race, since there is so much intra-familial variation.