By Furqan Ali

A review from Ink-e-Lab.

Publisher: Folio Books

Author: Ammar Ali Qureshi

Pages: 228

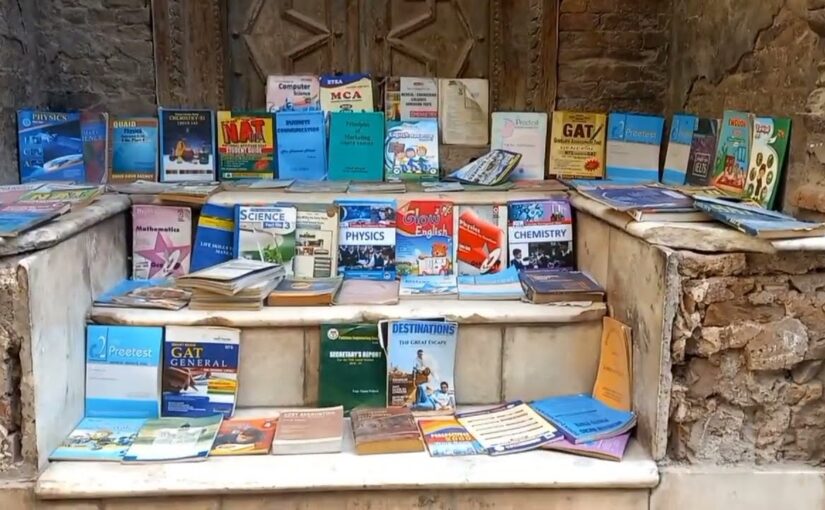

According to a Gallup survey, 75% of people claim not to read books at all. Mind you, this survey is from 2019 and by 2025, the figure has likely deteriorated even further; social media has drastically decimated our attention spans. A book, being a far more demanding form of engagement, often feels too formidable. People now struggle to read even a full 1,000 words op-ed, let alone something verbose. Many skim through posts on X, LinkedIn, or even long WhatsApp messages. And for those who do feel the urge to read, they’re often left perplexed: what should they read?

And that’s where book reviews come in: book reviews offer several valuable benefits for readers, writers, and the broader literary community. They help readers make informed decisions by summarizing a book’s content, style, and strengths or weaknesses, ultimately saving time and guiding personal preferences. Albeit, it is not a replacement of the whole corpus at all.

Reviews also deepen understanding by unpacking complex themes, symbolism, or context that casual readers might overlook. Additionally, they encourage critical thinking and discussion, as they often present arguments and interpretations that spark dialogue.

For writers, reviews provide constructive feedback and insight into how their work is being received, while also offering exposure, especially to lesser-known authors, by promoting diverse voices and hidden literary gems. Overall, reviews enrich the reading experience and foster a thoughtful culture of engagement with books. And the impending book under discussion does all of this and more.

Ammar Ali Qureshi’s Views and Reviews is a compilation of articles written across five cities spanning three continents over the past 15 years. One might call it a ‘labour of love’—a testament to his deep affection for books, inherited from his parents, both students of history, who allowed him to devour every book in their home. Even today, the library he has posted online reflects this passion, curated with care and brimming with crème de la crème titles.

The idea of writing these pieces draws inspiration from A.J.P. Taylor, the most popular and provocative British historian of the 20th century, who authored around 1,600 book reviews. This book, of course, is much slimmer compared to Taylor’s prolific output, yet it spans a wide range of subjects: history, politics, the economy and governance structures, nationalism, notable personalities, poetry, and more.

One striking piece, included in the first section, covers the exiled prince I had never heard of before, Maharaja Daleep Singh, son of Maharaja Ranjit Singh. The author’s review captures the deep melancholy of the story: the fall of one of the fiercest and most formidable reigns faced by the British, stretching from 1799 to 1849—from the southern districts of Punjab to Afghanistan and Kashmir. Ranjit Singh’s feat was a remarkable historical achievement.

The loss of this indigenous Punjabi kingdom, the confiscation of the Koh-i-Noor, Daleep’s dethronement at the age of ten, his coerced conversion to Christianity, his exile to England, and eventually his re-embrace of Sikhism, these form a profoundly tragic arc. He died penniless in a Paris hotel room, carrying the burdens of resentment and betrayal to the very end. The first section of the book, “Historical Perspectives on Punjab,” reads like a lament from a son mourning his lost mother, Punjab.

The second section turns to Pakistan. Among the essays, Pakistan and Iran: Neighbours of Many Surprises and Pakistan’s Middle Class and Islam particularly caught my attention. The former explores how Iran, under the Shah, was the first foreign head of state to visit Pakistan in 1950, became its largest bilateral donor—providing $800 million in loans and credit in the 1970s—supported Pakistan in the 1965 and 1971 wars, and yet, today, we face off against each other at a tense border.

The latter explores the rise of the new middle class, based on Dr Ammara Maqsood’s book The New Pakistani Middle Class. It focuses on how this class is more inclined toward a globalized form of Islam—seen as a legacy of Zia-ul-Haq and practiced by many Muslims in the West—rather than Wahhabism. However, Ammar points out the frequent conflation between the two, especially given the influence of Saudi funding. This stands in contrast to the older middle class, which projected a softer image of Pakistan.

In the third section, the article on Iqbal, “Iqbal — Love Letter to Persia,” reveals his (Iqbal’s) deep love for Persia: the language (of over 12,000 verses he composed, around 7,000 are in Persian), and Persian history especially the Persian conquest, which he considered most significant in the history of Islam, as reflected in his doctoral thesis. Iqbal’s admiration was reciprocated by prominent Persians, including Iran’s poet laureate Mohammad-Taqi Bahar, Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh, and influential figures like Ali Shariati (the ideologue of the Iranian Revolution) and Ali Khamenei (Supreme Leader of Iran).

Ammar quotes,

“Although the language of Hind is sweet as sugar / Yet sweeter is the fashion of Persian speech / My mind was enchanted by its loveliness / My pen became a twig of the Burning Bush / Because of the loftiness of my thoughts / Persian alone is suitable to them.”

The fourth section focuses on governance, particularly how corruption and the absence of a robust justice system fuel crony capitalism, weaken public service delivery, stifle economic growth, hinder innovation, crowd out investment, erode public trust, nudge religious extremism and reinforce elitism, among other consequences.

The fifth section, focused on personalities and memoirs, features intriguing pieces on figures such as Karl Marx—described as a “Prophet of Revolutions”—and Nur Jahan, the only Mughal queen to have her name inscribed on coins, who effectively ruled Jahangir’s empire for 15 of his 21 years on the throne. It explores the enduring influence of their legacies and the lessons they continue to offer, even after centuries. He quotes Robert Heilbroner from his book The Worldly Philosophers:

“We turn to Marx, therefore, not because he is infallible, but because he is inescapable.”

The sixth section shifts to global history, touching upon the rise and fall of Eastern and Western powers, the miscalculations of the Afghan war, Robert Fisk’s life amidst global upheavals, diplomatic failures, Obama’s failures, the rise of Trump, and much more. But I’ll stop here, I wouldn’t want to spoil it by revealing everything in it.

What elevates Ammar’s work is that his reviews are not mere summaries. He weaves history, politics, identity, and contemporary relevance into his analysis. He doesn’t shy away from highlighting contradictions or calling for critical engagement. His essays are not just about books, but about how to read, how to wrestle with ideas, how to cherish curiosity, and how to think.

In an age of vanishing attention spans, Views and Reviews is not only a literary respite, it is a call to return to depth, nuance, and the quiet joy of thoughtful reading.