Chennai, without any doubt, is one of the better cities in the country. I agree with many of the issues raised by XTM here. Along with Hyderabad, Ahmedabad, and Bangalore, Chennai continues to fare better in many aspects of life compared to Mumbai, Delhi, Kolkata, and even Pune.

My Experience

While I appreciated the cleanliness and infrastructure of Chennai, I cannot say I came away with the same impression as XTM. Of all the Indian cities I have visited, I found Chennai less hospitable than Ahmedabad, Hyderabad, or Delhi. Even as a fluent English speaker, I struggled to hail autos or get directions. Surprisingly, I did not face this issue in the rest of Tamil Nadu. For older Hindi speakers with limited English, the experience is even worse. The issue is not simply language, but linguistic chauvinism (also present in Karnataka and Maharashtra, though to a lesser extent). A non-Tamil speaker often looks for Muslim individuals to ask for help in Chennai.

I had a wonderful time in Mamallapuram, enjoying the Pallava ruins and the beach, thanks to a very helpful Muslim auto driver. But enough of auto-wala stories.

Culture and Politics

Without comparing cities directly, it is important to recognize that culture may play a role in Chennai’s successes. However, correlation should not be confused with causation, and credit should not be misplaced. Any link between Chennai’s well-being and Dravidianism is tenuous or purely incidental at best. While successive Tamil Nadu governments aligned with Dravidianism have been relatively successful (especially compared to the North) in providing welfare nets, what direct connection do these well-run policies have with Dravidianism?

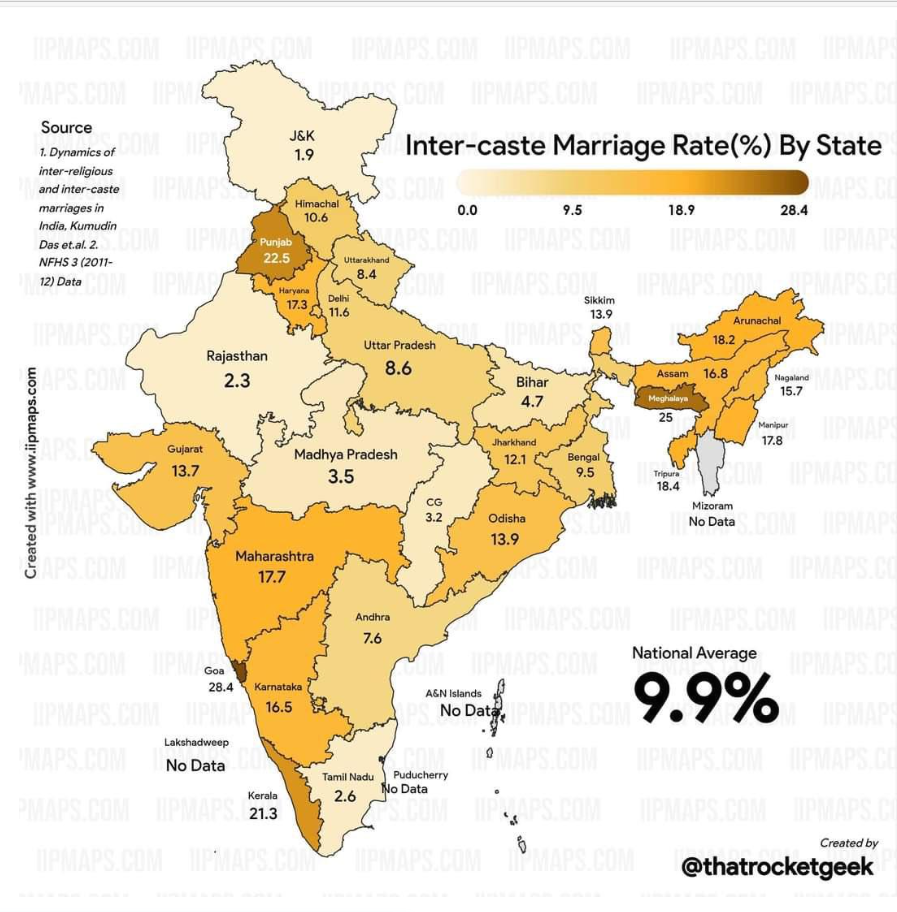

Let us compare Tamil Nadu with the rest of India on the metric that Dravidian progressivism claims to address: CASTE

Link:

Scroll piece : Caste endogamy is also unaffected by how developed or industrialised a particular state is, even though Indian states differ widely in this aspect. Tamil Nadu, while relatively industrialised, has a caste endogamy rate of 97% while underdeveloped Odisha’s is 88%, as per a study by researchers Kumudini Das, Kailash Chandra Das, Tarun Kumar Roy and Pradeep Kumar Tripathy.

Put differently: caste endogamy seems unaffected by how anti-Brahminical or “progressive” a state claims to be. Tamil Nadu, the heart of the Dravidian movement, remains at below 3%, while Gujarat—often seen as Brahmanical and vegetarian—stands around 10% (15% in a 2010 study, though possibly overstated). However one frames it, Gujarat has more inter-caste marriages than Tamil Nadu.

Surprisingly, even Haryana and Punjab—traditionally associated with Khap Panchayats and honor culture—show significant inter-caste marriages, along with Gujarat, Maharashtra, Karnataka, and Kerala.

While data on Haryana, Punjab, and Goa is contested, Tamil Nadu consistently lags, whereas its neighbor Kerala consistently leads, along with Maharashtra.

Crossing from Kerala into Tamil Nadu, the difference is stark: one in five marriages in Kerala are inter-caste, compared to fewer than one in thirty in Tamil Nadu. Would it be fair to blame Dravidian politics for this? That claim has more merit than attributing Tamil Nadu’s successes to Dravidianism. Tamil Nadu ranks alongside Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Kashmir, while Karnataka, Kerala, and even Andhra/Telangana are far ahead.

Even Kashmir, with a 65% Muslim population, has an inter-caste marriage rate just below 2%, lower than Dravidian-ruled Tamil Nadu. So, after 500 years under a “casteless” religion and 100 years of “progressive” Dravidianism, both Kashmir and Tamil Nadu lag behind Gujarat, Bihar, and Uttar Pradesh.

Additional Observations

This data does not fit neat narratives. I was surprised to see higher percentages of rural inter-caste marriages. Rates are negatively correlated with wealth and income (more strongly with assets such as land). Landed communities show stronger caste endogamy, for historically and pragmatically clear reasons. That Brahmins, as a group, have the highest inter-caste marriage rates is unsurprising, given how progressive (some might say deracinated) Brahmins have become in India.

One social metric where Tamil Nadu performs well is female foeticide. Tamil Nadu and Kerala are among the leading states less affected by sex-selective abortions compared to the rest of India.

Tamil Brahmins have generally been more socially aloof compared to Brahmins elsewhere in India (both anecdotally and objectively) and disproportionately occupied government posts in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The Justice Party movement, which arose in response, was initially a elite-feudal project, though Periyar’s early movement (also virulently anti-Brahmin) was more inclusive of Dalits and non-dominant castes. Over time, while retaining its anti-Brahmin rhetoric, the movement became a proxy for domination by landed and wealthy communities. Dravidianism today (or perhaps always) resembles what it claimed to oppose—Brahmanism. The dominant elites have simply shifted from Brahmins and the British to others who hold power today. Hatred alone does not create positive change.

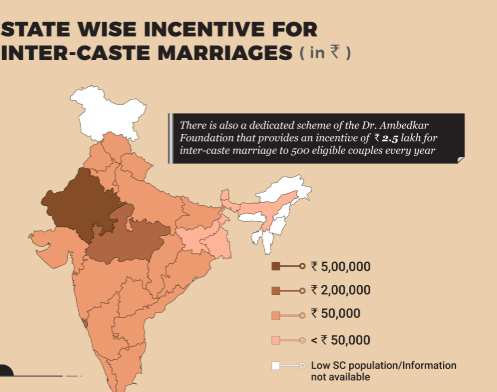

It seems Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh understood the incentives for reform, while Tamil Nadu did not.

Anecdotes or caste violence are often dismissed when praising the Dravidian model of social progressivism. Comparative caste violence data is brushed aside under claims of underreporting or lack of Dalit assertion in other regions. But caste endogamy cannot be ignored. If anything that truly encapsulates Caste is endogamy.

Post Script:

Tamil politicians, both DMK and AIADMK, have run better governments in terms of welfare, industrialization, and infrastructure, and they deserve credit for that. However, linking these achievements to culture may not be wise. Geography is a more convincing explanation.