The Guardian has a long piece about Parsis, The last of the Zoroastrians. The author is the child of a Parsi mother who married a white Briton. Though he brings his own perspective into the piece, I appreciated that he did not let it overwhelm the overall narrative. The star are the Parsis themselves, not his own personal journey and viewpoints.

The Guardian has a long piece about Parsis, The last of the Zoroastrians. The author is the child of a Parsi mother who married a white Briton. Though he brings his own perspective into the piece, I appreciated that he did not let it overwhelm the overall narrative. The star are the Parsis themselves, not his own personal journey and viewpoints.

In relation to the Parsis, there are two aspects in the Indian context that warrant exploration

– high levels of cultural assimilation

– high levels of cultural separateness

These seem strange outside of India, but they make sense within India. The Zoroastrian priests who migrated to what became Gujurat integrated themselves into the local landscape as an endogamous community. From a genetic perspective, the best overview is “Like sugar in milk”: reconstructing the genetic history of the Parsi population:

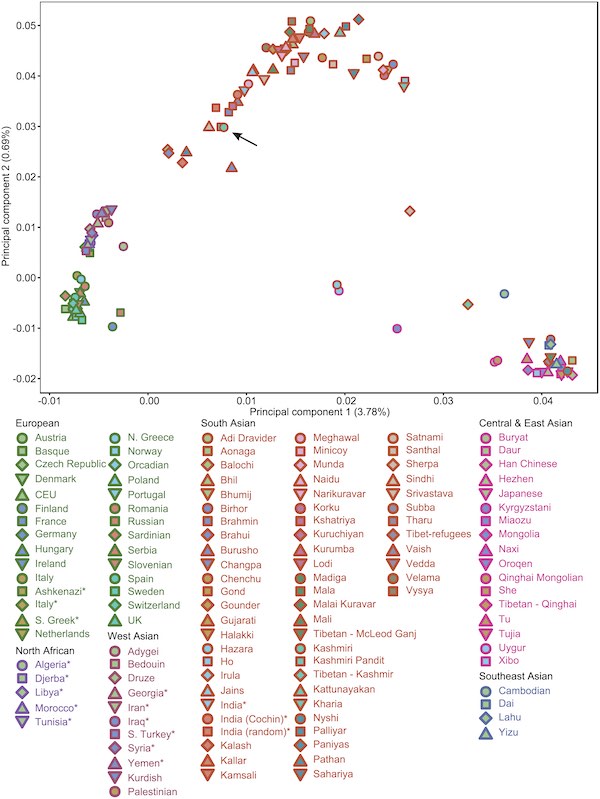

Among present-day populations, the Parsis are genetically closest to Iranian and the Caucasus populations rather than their South Asian neighbors. They also share the highest number of haplotypes with present-day Iranians and we estimate that the admixture of the Parsis with Indian populations occurred ~1,200 years ago. Enriched homozygosity in the Parsi reflects their recent isolation and inbreeding. We also observed 48% South-Asian-specific mitochondrial lineages among the ancient samples, which might have resulted from the assimilation of local females during the initial settlement. Finally, we show that Parsis are genetically closer to Neolithic Iranians than to modern Iranians, who have witnessed a more recent wave of admixture from the Near East.

The major finding is that most of the ancestry, on the order of 75%, of Indian Parsis is generically Iranian. On the order of 25% is “indigenous”, probably Gujurati. The fact that the proportion of mtDNA, the maternal lineage, is closer to 50% in both modern and ancient samples, indicates that the mixing with Indians occurred through taking local women as brides. Further genetic investigation in the above paper suggests that this was not a recurrent feature. In other words, once the Zoroastrian community in Gujurat was large enough, it became entirely endogamous.

And yet the Parsis speak Gujurati (or in Pakistan Sindhi and Urdu), and in many ways are culturally quite indigenized.

I bring this up because this portion of the above piece I’ve seen elsewhere:

The small community of Iranian Zoroastrians is even more liberal, allowing female priests, and there are also nascent neo-Zoroastrian movements in parts of the Middle East.

I have read repeatedly that Iranian Zoroastrians are more “liberal” when it comes to the issue of religious endogamy. The term “liberal” indicates innovation. But if you look at the historiography it seems clear that though Zoroastrianism was strongly connected to Iranian-speaking people, it was not exclusive to them. Zoroastrianism was cultivated and encouraged by the Sassanians in much of the Caucasus, and it spread into Central Asia, even amongst some Turkic groups, before the rise of Islam.

Zoroastrianism was not aggressively proselytizing but before 600 A.D. neither was Christianity outside of the Roman Empire. This is not a well-known fact due to the religion’s gradual diffusion to non-Roman societies, such as Ireland and Ethiopia, but before Gregory the Great missions to barbarian peoples were not organized from the Metropole but were ad hoc (the Byzantines eventually began centrally organized missionary activities after 600 A.D., but they were never as thorough or enthusiastic as the Western Christians). Our understanding of Zoroastrianism then may not be clear because the religion went into decline during a transformative period in world history when the religious boundaries and formations we see around us were still inchoate.

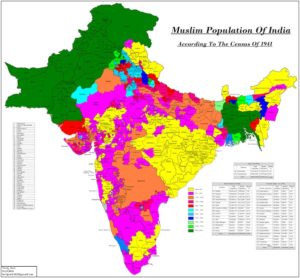

The major takeaway from all this is that strenuous Parsi arguments for the ethnic character of Zoroastrianism are a reflection not of their Iranian religious background, but their Indian cultural milieu. Zoroastrian “traditionalists” in India are actually Indian traditionalists, who have internalized an innovation to allow for integration into South Asia. And, I would argue some of the same applies to Indian “traditionalists,” whose cultural adaptations to the “shock” of Turco-Muslim domination resulted in the strengthening of particular tendencies within Indian culture that were already preexistent.

Since about 2006 I’ve had to write the same post again and again due to the nature of my audience: religion is not the purview of technically oriented nerds, and technically oriented nerds just don’t “get” it intuitively. This is something that is relevant to me personally, because I am myself a technically oriented nerd, and I just don’t “get” religion.

Since about 2006 I’ve had to write the same post again and again due to the nature of my audience: religion is not the purview of technically oriented nerds, and technically oriented nerds just don’t “get” it intuitively. This is something that is relevant to me personally, because I am myself a technically oriented nerd, and I just don’t “get” religion.

Between 1995 and 2005 I went through a “Richard Dawkins” phase. As it happens, I met Dawkins casually in 1995 at a talk and had been reading his biology works. I was not particularly interested in his religious commentary. Rather, I read books such as Atheism: A Philosophical Justification or relevant portions of Summa Theologica. I plumbed the depths of ontological, teleological, and cosmological arguments. I engaged with the works of men such as Norman Malcolm and Richard Swinburne.

Between 1995 and 2005 I went through a “Richard Dawkins” phase. As it happens, I met Dawkins casually in 1995 at a talk and had been reading his biology works. I was not particularly interested in his religious commentary. Rather, I read books such as Atheism: A Philosophical Justification or relevant portions of Summa Theologica. I plumbed the depths of ontological, teleological, and cosmological arguments. I engaged with the works of men such as Norman Malcolm and Richard Swinburne.