A recent comment revived this excellent older post by The Emissary, so we’re bringing it back to the front page. Our archives are strong, and worth revisiting.

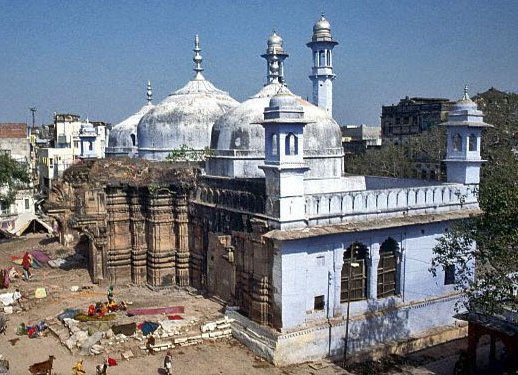

There are various images I could have chosen to represent Islam in India. One could use the Taj Mahal, the ruins of a temple, a mural of a bloody battlefield, Muhammed Ali Jinnah, the beauty of Indo-Islamic art, and so many more images. Islam in India has had a long and complicated history. People have argued till tongues became swords over the impact of Islam on India and its relation to the people. Indeed, one could argue the most lasting impact of Islam on the subcontinent is its partitioning by Jinnah and his cohorts on that fateful day in 1947; when Mahatma Gandhi’s dream was ripped apart in a bloody separation of an ancient people.

But while this post will examine the past, I want to focus on the now and future of Islam in India. That is why I chose to have possibly the most beloved Indian in history, Dr. APJ Abdul Kalam, as the heading photo for this post. But we will talk more about him and what he encapsulates later; let’s take a look back at the sands of time.

(No) Remorse

I’ll be upfront and say I have an overall negative view on Islam’s past impact on India.

One of the most eminent historians ever, Will Durant, wrote this of the Islamic invasion of India:

“The Islamic conquest of India is probably the bloodiest story in history. It is a discouraging tale, for its evident moral is that civilization is a precious good, whose delicate complex of order and freedom, culture and peace, can at any moment be overthrown by barbarians invading from without or multiplying within.” – The Story of Civilization: Our Oriental Heritage page 459.

History has witnessed monsters that have killed millions – Genghis Khan, Alexander the Great, the Spanish conquistadors of America, etc… – but Durant singles out the hundreds of years long siege of Islam on India as the bloodiest of them all. Millions dead, raped, or forcibly converted. Temples, universities, and entire cities lay in ruin. An indigenous culture repressed and humiliated all because they believed in a different god.

While this image is grave, it’s not what I want you to leave with in regards to India’s Islam. Amongst the carnage and deep darkness that swept the subcontinent, there was light.

Din-I-Ilahi

Islamic rule in India produced great art, literature, opulence, but most beautiful of all – syncretism, the trademark of India. Akbar was one of the first rulers who recognized the underlying similarities between Islam and Hinduism; so much so, that he integrated both religions into his own system – Din-I-Ilahi – or the Religion of God (original…I know).

The Varanasi poet and weaver, Kabir, won the hearts of both Hindus and Muslims. His poetry would be recited till this day as an epitaph to his spirit of spiritual harmony. His musings would change how religion was practiced across North India, including influencing a newly born religion – Sikhism. Guru Nanak would continue Kabir’s compare and contrasting of Hinduism and Islam, while providing his own unique philosophy.

(

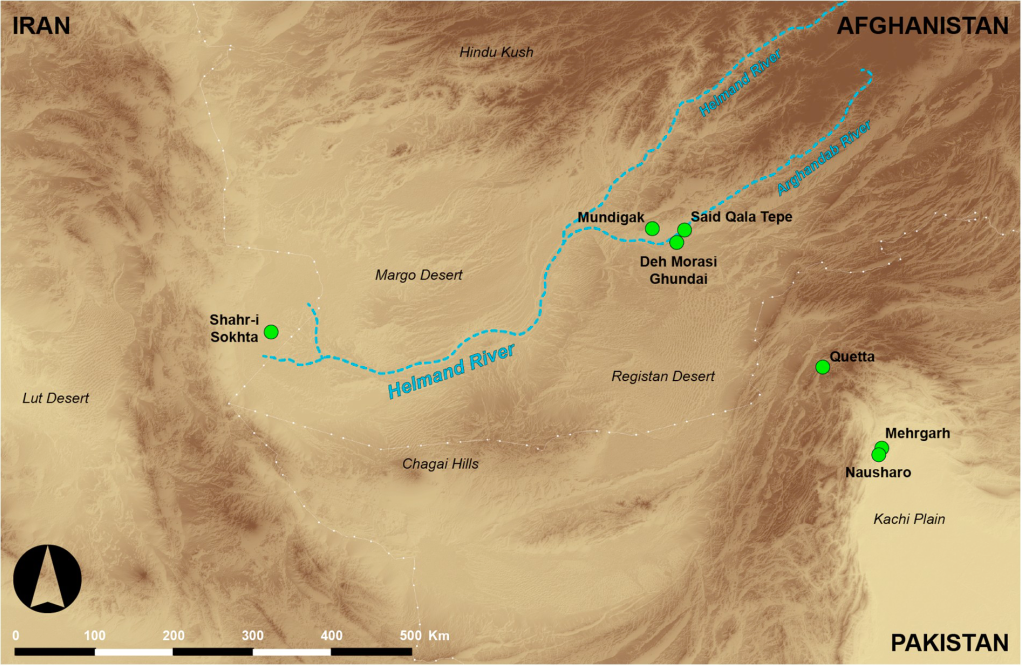

( (Mundigak, Afghanistan)

(Mundigak, Afghanistan) (Burnt Building, Shahr-i-Sokhta)

(Burnt Building, Shahr-i-Sokhta)

A friend sent me this piece,

A friend sent me this piece,