One of the things that I admitted when reflecting on where I’ve been wrong, is that my default stance is to be somewhat isolationist because international entanglements are so complex. Some critics always wonder why I use such a simple heuristic, why not evaluate on a case by case basis?

One of the things that I admitted when reflecting on where I’ve been wrong, is that my default stance is to be somewhat isolationist because international entanglements are so complex. Some critics always wonder why I use such a simple heuristic, why not evaluate on a case by case basis?

At the extreme, this is obviously what would happen. But most cases are not at the extreme. The reality is I know more about history and geography than the vast majority of people, and I just don’t feel comfortable offering definitive judgment on many issues.

At the extreme, this is obviously what would happen. But most cases are not at the extreme. The reality is I know more about history and geography than the vast majority of people, and I just don’t feel comfortable offering definitive judgment on many issues.

In the USA today the Right is pro-Israel to a default, to such an extent that it strikes me that they are as pro-Israel as they are pro-American. At least their in their rhetorical posture. Similarly, the Left is now pro-Palestine to a very great extent.

We could conclude that both the Right and Left have thought through their positions deeply and come to a reasoned position, but the reality is that these are just tribal politics. A subset of the Right adheres to a philo-Israeli theological position that has emerged in the last few decades, and these dictate the terms for the broader Right. Similarly, a small group of activists have kept and amplified the fire of 1970s Left nationalism which aligned with Palestine, and merged with more mainstream “social justice” views so that the pro-Palestinian position is now the Left position.

This is the case with many issues. Tribal politics and coalitional affinities drive solidarity and opinions. When your enemy was the Nazis, things get much easier. But these are very rare cases. Reality is more complex.

Which gets to why I used Ilhan Omar and Sarah Palin to illustrate this post. Both are very sincere and very stupid. So they have strong unnuanced opinions on foreign affairs, even if they could barely navigate a map. They are the best models for “hash tag activists.”

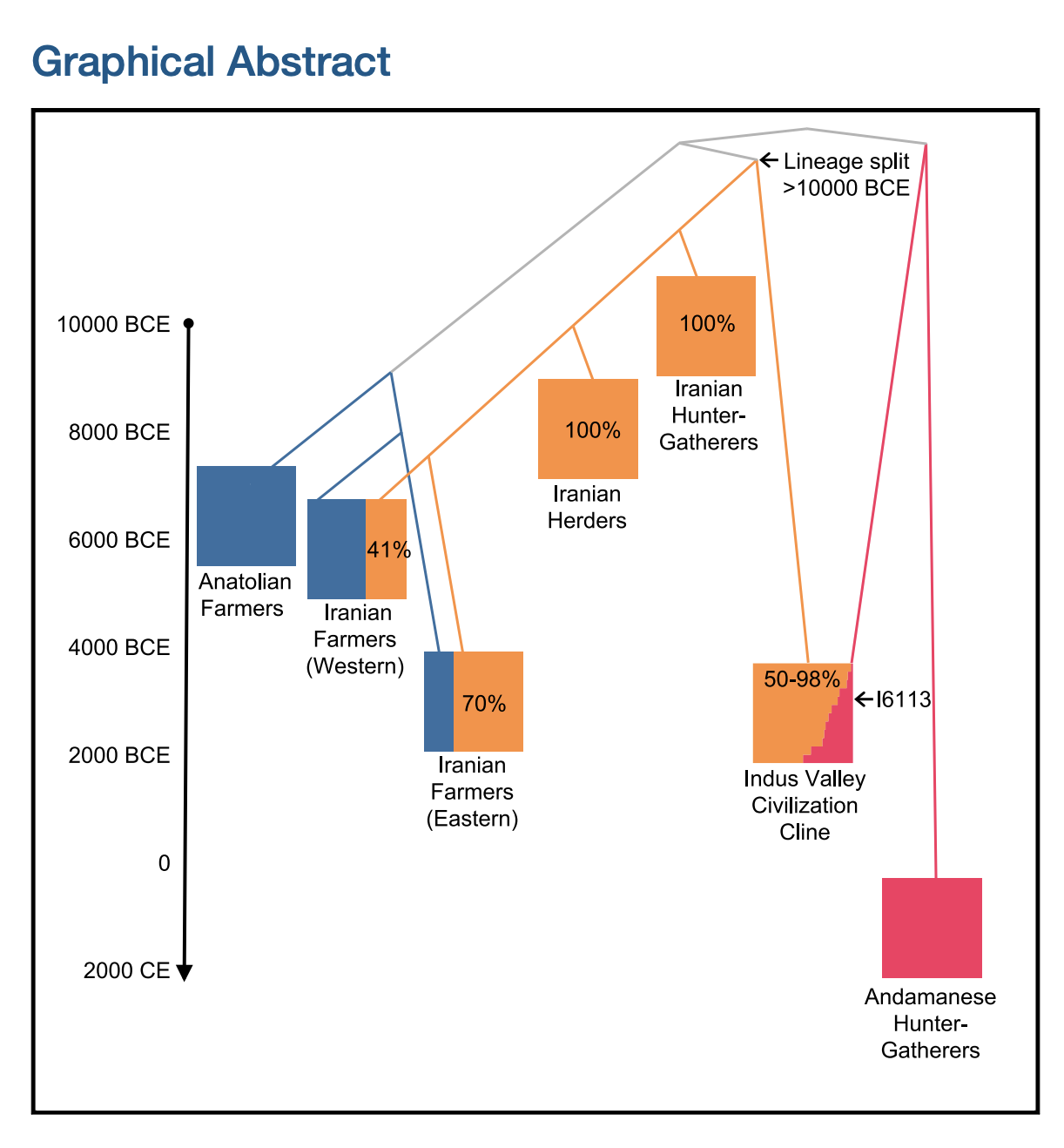

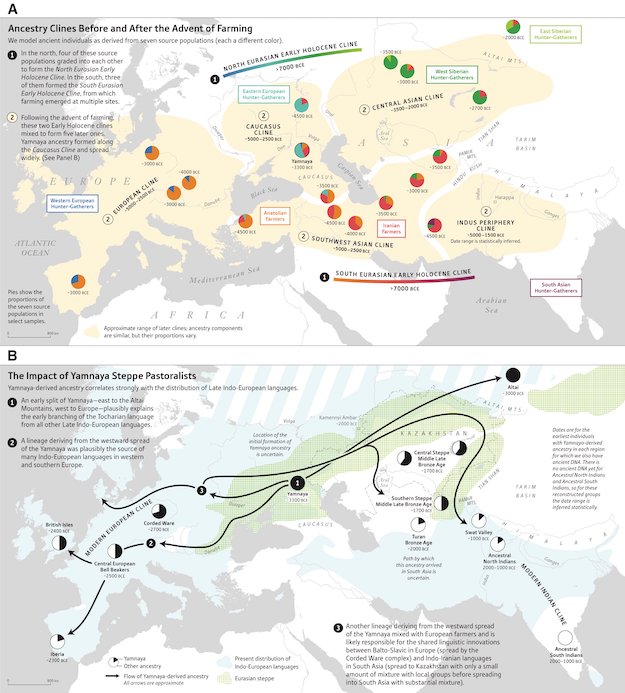

In ~48 hours I will be recording a podcast with Vagheesh Narasimhan, first author of The formation of human populations in South and Central Asia, and the second author of An Ancient Harappan Genome Lacks Ancestry from Steppe Pastoralists or Iranian Farmers. We’ll have lots to talk about but open to taking questions from readers as well.

In ~48 hours I will be recording a podcast with Vagheesh Narasimhan, first author of The formation of human populations in South and Central Asia, and the second author of An Ancient Harappan Genome Lacks Ancestry from Steppe Pastoralists or Iranian Farmers. We’ll have lots to talk about but open to taking questions from readers as well.

One of the things that I

One of the things that I  At the extreme, this is obviously what would happen. But most cases are not at the extreme. The reality is I know more about history and geography than the vast majority of people, and I just don’t feel comfortable offering definitive judgment on many issues.

At the extreme, this is obviously what would happen. But most cases are not at the extreme. The reality is I know more about history and geography than the vast majority of people, and I just don’t feel comfortable offering definitive judgment on many issues.