Postscript: There is another Bannon profile in (of all places) The Hollywood Reporter that is worth a look. The man is serious. And he thinks he is Thomas Cromwell. Which is interesting, because some of you may remember that Cromwell was beheaded. By Henry the VIIIth, the king he so loyally served.

Buzzfeed has an article that consists of the verbatim remarks of Stephen Bannon at a Vatican conference in 2014. Since this was pre-Trump, these are not filtered for the presidential campaign (though some of them may still be filtered the way all ideologues filter their public pronouncements keeping “the cause” in view).

These remarks are interesting. That he is totally committed to a global war with Islam is no surprise. But I urge you to read the rest. And comment. Some of you will no doubt agree with his elite-bashing (and/or his Islam bashing), but there is a lot more in there. And he is now senior adviser to the US president. The worldview is definitely at odds with prevailing Western opinion, but is it “thick enough” and does it overlap enough with reality to stand on its own? and what happens if you try to put it into effect?

What do you think?

I think he is wrong on several simple matters of fact, not just on ideology (which i find wrong in any case). The notion of a historic Judeo-Christian West that has stood as one against the Islamic tide for centuries is just bunk. Judeo is a new apellation and he knows it. Christendom, yes, Judeo-Christian, certainly not. Which makes you think that he may have some nasty surprises up his sleeve for the Jews. But since he is focused on first smashing the Islamic threat, he will probably be good to Israel, for now. Those Jews who regard weak-minded liberal Western Jews as traitors (or at least, as softies) may be happy to embrace him. For now. Like Stalin did with Hitler, both parties can think “I am using him, for now, to become stronger”. One party will of course turn out to be wrong. But all that is speculation. It may be that he is genuinely ignorant and really does think “Judeo-Christian civilization” has been bravely fighting Islam for 1400 years. We will see.. (Whatever his own inner beliefs, the Alt-Right he has promoted is not shy in its attitude towards Jews…if you check out the Alt-Right sites, you may find their obsession with ovens and trains less than reassuring).

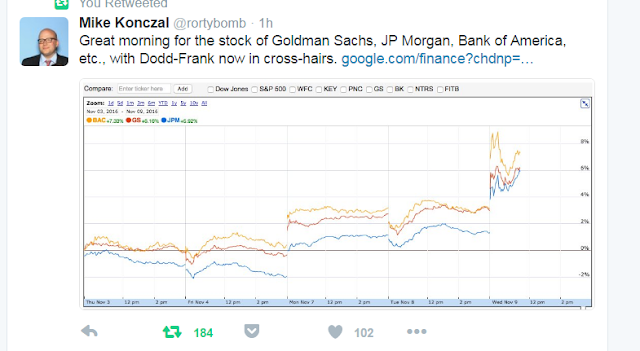

His whole theory about the only right kind of capitalism being “Judeo-Christian” seems shaky to me as well (though in this case he may not know it; i.e. these may be his sincere beliefs) but I will let experts comment. In fact, the whole banks and crony capitalist issue I will leave to the better informed. I dont think that is the scary part.

The notion that “strong nations make good neighbors”is high grade, class A bullshit and he likely knows it, but who knows. He may not be that well informed. And his notion that Putin and the West can join hands in a grand White Christian alliance to first beat the shit out of Muslim barbarians is also bunk. Putin would much rather eat the Baltics, the Ukraine and maybe even Poland before he seriously starts any extermination campaign in the Stans.

China and Japan get no significant mention.

India gets approvingly cited for electing Modi, but in the greater scheme of things must surely prepare for Christianization if team Bannon wins the war (when push comes to shove, would you expect Bannon to stand with the Evangelicals or with Hindu nationalism? Do the math). Interin calculation is another matter. See Stalin and Hitler above. Some in India will no doubt see possibilities in the medium term. I don’t because I think this is a flaky worldview that will damage the USA and the current system and not build anything better. India still needs the current system to grow in. Thats just my opinion.

Overall, the current world system is to be trashed. In the melee that follows, what civilizations have the coherence and the strength to fight it out. And who wins? is a less violent reform possible? Is HE a less violent reformer?

,

I still hope (and even expect) that we will not go too far from the current (irredeemably corrupt?) system, but here you have it: the senior adviser to Donald Trump, President Elect. President Elect IN the current system.

Chunks of his remarks pasted below. The original is at Buzzfeed.

The remarks — beamed into a small conference room in a 15th-century marble palace in a secluded corner of the Vatican — were part of a 50-minute Q&A during a conference focused on poverty hosted by the Human Dignity Institute, which BuzzFeed News attended as part of its coverage of the rise of Europe’s religious right. The group was founded by Benjamin Harnwell, a longtime aide to Conservative member of the European Parliament Nirj Deva to promote a “Christian voice” in European politics. The group has ties to some of the most conservative factions inside the Catholic Church; Cardinal Raymond Burke, one of the most vocal critics of Pope Francis who was ousted from a senior Vatican position in 2014, is chair of the group’s advisory board.

The transcript begins 90 seconds into the then-Breitbart News chairman’s remarks because microphone placement made the opening mostly unintelligible, but you can hear the whole recording at the bottom of the post.

Here is what he said, unedited: (Big chunks, but not all, you have to go to the site to read the full thing, i recommend you do, i had no time to focus on the best excerpts)

Steve Bannon: [World War I] triggered a century of barbaric — unparalleled in mankind’s history — virtually 180 to 200 million people were killed in the 20th century, and I believe that, you know, hundreds of years from now when they look back, we’re children of that: We’re children of that barbarity. This will be looked at almost as a new Dark Age.

But the thing that got us out of it, the organizing principle that met this, was not just the heroism of our people — whether it was French resistance fighters, whether it was the Polish resistance fighters, or it’s the young men from Kansas City or the Midwest who stormed the beaches of Normandy, commandos in England that fought with the Royal Air Force, that fought this great war, really the Judeo-Christian West versus atheists, right? The underlying principle is an enlightened form of capitalism, that capitalism really gave us the wherewithal. It kind of organized and built the materials needed to support, whether it’s the Soviet Union, England, the United States, and eventually to take back continental Europe and to beat back a barbaric empire in the Far East.

That capitalism really generated tremendous wealth. And that wealth was really distributed among a middle class, a rising middle class, people who come from really working-class environments and created what we really call a Pax Americana. It was many, many years and decades of peace. And I believe we’ve come partly offtrack in the years since the fall of the Soviet Union and we’re starting now in the 21st century, which I believe, strongly, is a crisis both of our church, a crisis of our faith, a crisis of the West, a crisis of capitalism.

“I believe we’ve come partly offtrack in the years since the fall of the Soviet Union and we’re starting now in the 21st century, which I believe, strongly, is a crisis both of our church, a crisis of our faith, a crisis of the West, a crisis of capitalism.”

And we’re at the end stages of a very brutal and bloody conflict, of which if the people in this room, the people in the church, do not bind together and really form what I feel is an aspect of the church militant, to really be able to not just stand with our beliefs, but to fight for our beliefs against this new barbarity that’s starting, that will completely eradicate everything that we’ve been bequeathed over the last 2,000, 2,500 years.

Now, what I mean by that specifically: I think that you’re seeing three kinds of converging tendencies: One is a form of capitalism that is taken away from the underlying spiritual and moral foundations of Christianity and, really, Judeo-Christian belief.

I see that every day. I’m a very practical, pragmatic capitalist. I was trained at Goldman Sachs, I went to Harvard Business School, I was as hard-nosed a capitalist as you get. I specialized in media, in investing in media companies, and it’s a very, very tough environment. And you’ve had a fairly good track record. So I don’t want this to kinda sound namby-pamby, “Let’s all hold hands and sing ‘Kumbaya’ around capitalism.”

But there’s a strand of capitalism today — two strands of it, that are very disturbing.

One is state-sponsored capitalism. And that’s the capitalism you see in China and Russia. I believe it’s what Holy Father [Pope Francis] has seen for most of his life in places like Argentina, where you have this kind of crony capitalism of people that are involved with these military powers-that-be in the government, and it forms a brutal form of capitalism that is really about creating wealth and creating value for a very small subset of people. And it doesn’t spread the tremendous value creation throughout broader distribution patterns that were seen really in the 20th century.

The second form of capitalism that I feel is almost as disturbing, is what I call the Ayn Rand or the Objectivist School of libertarian capitalism. And, look, I’m a big believer in a lot of libertarianism. I have many many friends that’s a very big part of the conservative movement — whether it’s the UKIP movement in England, it’s many of the underpinnings of the populist movement in Europe, and particularly in the United States.

However, that form of capitalism is quite different when you really look at it to what I call the “enlightened capitalism” of the Judeo-Christian West. It is a capitalism that really looks to make people commodities, and to objectify people, and to use them almost — as many of the precepts of Marx — and that is a form of capitalism, particularly to a younger generation [that] they’re really finding quite attractive. And if they don’t see another alternative, it’s going to be an alternative that they gravitate to under this kind of rubric of “personal freedom.”

“Look at what’s happening in ISIS … look at the sophistication of which they’ve taken the tools of capitalism … at what they’ve done with Twitter and Facebook.”

The other tendency is an immense secularization of the West. And I know we’ve talked about secularization for a long time, but if you look at younger people, especially millennials under 30, the overwhelming drive of popular culture is to absolutely secularize this rising iteration.

Now that call converges with something we have to face, and it’s a very unpleasant topic, but we are in an outright war against jihadist Islamic fascism. And this war is, I think, metastasizing far quicker than governments can handle it.

If you look at what’s happening in ISIS, which is the Islamic State of Syria and the Levant, that is now currently forming the caliphate that is having a military drive on Baghdad, if you look at the sophistication of which they’ve taken the tools of capitalism. If you look at what they’ve done with Twitter and Facebook and modern ways to fundraise, and to use crowdsourcing to fund, besides all the access to weapons, over the last couple days they have had a radical program of taking kids and trying to turn them into bombers. They have driven 50,000 Christians out of a town near the Kurdish border. We have video that we’re putting up later today on Breitbart where they’ve took 50 hostages and thrown them off a cliff in Iraq.

That war is expanding and it’s metastasizing to sub-Saharan Africa. We have Boko Haram and other groups that will eventually partner with ISIS in this global war, and it is, unfortunately, something that we’re going to have to face, and we’re going to have to face very quickly.

So I think the discussion of, should we put a cap on wealth creation and distribution? It’s something that should be at the heart of every Christian that is a capitalist — “What is the purpose of whatever I’m doing with this wealth? What is the purpose of what I’m doing with the ability that God has given us, that divine providence has given us to actually be a creator of jobs and a creator of wealth?”

I think it really behooves all of us to really take a hard look and make sure that we are reinvesting that back into positive things. But also to make sure that we understand that we’re at the very beginning stages of a global conflict, and if we do not bind together as partners with others in other countries that this conflict is only going to metastasize.

They have a Twitter account up today, ISIS does, about turning the United States into a “river of blood” if it comes in and tries to defend the city of Baghdad. And trust me, that is going to come to Europe. That is going to come to Central Europe, it’s going to come to Western Europe, it’s going to come to the United Kingdom. And so I think we are in a crisis of the underpinnings of capitalism, and on top of that we’re now, I believe, at the beginning stages of a global war against Islamic fascism.

“With all the baggage that those [right-wing] groups bring — and trust me, a lot of them bring a lot of baggage, both ethnically and racially— but we think that will all be worked through with time.”

Benjamin Harnwell, Human Dignity Institute: Thank you, Steve. That was a fascinating, fascinating overview. I am particularly struck by your argument, then, that in fact, capitalism would spread around the world based on the Judeo-Christian foundation is, in fact, something that can create peace through peoples rather than antagonism, which is often a point not sufficiently appreciated. Before I turn behind me to take a question —

Bannon: One thing I want to make sure of, if you look at the leaders of capitalism at that time, when capitalism was I believe at its highest flower and spreading its benefits to most of mankind, almost all of those capitalists were strong believers in the Judeo-Christian West. They were either active participants in the Jewish faith, they were active participants in the Christians’ faith, and they took their beliefs, and the underpinnings of their beliefs was manifested in the work they did. And I think that’s incredibly important and something that would really become unmoored. I can see this on Wall Street today — I can see this with the securitization of everything is that, everything is looked at as a securitization opportunity. People are looked at as commodities. I don’t believe that our forefathers had that same belief.

Harnwell: Over the course of this conference we’ve heard from various points of view regarding alleviation of poverty. We’ve heard from the center-left perspective, we’ve heard from the socialist perspective, we’ve heard from the Christian democrat, if you will, perspective. What particularly interests me about your point of view Steve, to talk specifically about your work, Breitbart is very close to the tea party movement. So I’m just wondering whether you could tell me about if in the current flow of contemporary politics — first tell us a little bit about Breitbart, what the mission is, and then tell me about the reach that you have and then could you say a little bit about the current dynamic of what’s going on at the moment in the States.

Bannon: Outside of Fox News and the Drudge Report, we’re the third-largest conservative news site and, quite frankly, we have a bigger global reach than even Fox. And that’s why we’re expanding so much internationally.

Look, we believe — strongly — that there is a global tea party movement. We’ve seen that. We were the first group to get in and start reporting on things like UKIP and Front National and other center right. With all the baggage that those groups bring — and trust me, a lot of them bring a lot of baggage, both ethnically and racially — but we think that will all be worked through with time.

The central thing that binds that all together is a center-right populist movement of really the middle class, the working men and women in the world who are just tired of being dictated to by what we call the party of Davos. A group of kind of — we’re not conspiracy-theory guys, but there’s certainly — and I could see this when I worked at Goldman Sachs — there are people in New York that feel closer to people in London and in Berlin than they do to people in Kansas and in Colorado, and they have more of this elite mentality that they’re going to dictate to everybody how the world’s going to be run.

….

“Putin’s … very, very very intelligent. I can see this in the United States where he’s playing very strongly to social conservatives about his message about more traditional values, so I think it’s something that we have to be very much on guard of.”

Now, with that, we are strong capitalists. And we believe in the benefits of capitalism. And, particularly, the harder-nosed the capitalism, the better. However, like I said, there’s two strands of capitalism that we’re quite concerned about.

One is crony capitalism, or what we call state-controlled capitalism, and that’s the big thing the tea party is fighting in the United States, and really the tea party’s biggest fight is not with the left, because we’re not there yet. The biggest fight the tea party has today is just like UKIP. UKIP’s biggest fight is with the Conservative Party.

The tea party in the United States’ biggest fight is with the the Republican establishment, which is really a collection of crony capitalists that feel that they have a different set of rules of how they’re going to comport themselves and how they’re going to run things. And, quite frankly, it’s the reason that the United States’ financial situation is so dire, particularly our balance sheet. We have virtually a hundred trillion dollars of unfunded liabilities. That is all because you’ve had this kind of crony capitalism in Washington, DC. The rise of Breitbart is directly tied to being the voice of that center-right opposition. And, quite frankly, we’re winning many, many victories.

On the social conservative side, we’re the voice of the anti-abortion movement, the voice of the traditional marriage movement, and I can tell you we’re winning victory after victory after victory. Things are turning around as people have a voice and have a platform of which they can use.

….

“That center-right revolt is really a global revolt. I think you’re going to see it in Latin America, I think you’re going to see it in Asia, I think you’ve already seen it in India.”

And you’re seeing that whether that was UKIP and Nigel Farage in the United Kingdom, whether it’s these groups in the Low Countries in Europe, whether it’s in France, there’s a new tea party in Germany. The theme is all the same. And the theme is middle-class and working-class people — they’re saying, “Hey, I’m working harder than I’ve ever worked. I’m getting less benefits than I’m ever getting through this, I’m incurring less wealth myself, and I’m seeing a system of fat cats who say they’re conservative and say they back capitalist principles, but all they’re doing is binding with corporatists.” Right? Corporatists, to garner all the benefits for themselves.

And that center-right revolt is really a global revolt. I think you’re going to see it in Latin America, I think you’re going to see it in Asia, I think you’ve already seen it in India. Modi’s great victory was very much based on these Reaganesque principles, so I think this is a global revolt, and we are very fortunate and proud to be the news site that is reporting that throughout the world.

Bannon: It’s exactly the same. Currently, if you read The Economist, you read the Financial Times this week, you’ll see there’s a relatively obscure agency in the federal government that is engaged in a huge fight that may lead to a government shutdown. It’s called the Export-Import Bank. And for years, it was a bank that helped finance things that other banks wouldn’t do. And what’s happening over time is that it’s metastasized to be a cheap form of financing to General Electric and to Boeing and to other large corporations. You get this financing from other places if they wanted to, but they’re putting this onto the middle-class taxpayers to support this.

“I’m not an expert in this, but it seems that [right-wing parties] have had some aspects that may be anti-Semitic or racial … My point is that over time it all gets kind of washed out, right?”

And the tea party is using this as an example of the cronyism. General Electric and these major corporations that are in bed with the federal government are not what we’d consider free-enterprise capitalists. We’re backers of entrepreneurial capitalists. They’re not. They’re what we call corporatist. They want to have more and more monopolistic power and they’re doing that kind of convergence with big government. And so the fight here — and that’s why the media’s been very late to this party — but the fight you’re seeing is between entrepreneur capitalism, and the Aspen Institute is a tremendous supporter of, and the people like the corporatists that are closer to the people like we think in Beijing and Moscow than they are to the entrepreneurial capitalist spirit of the United States.

Harnwell: Thanks, Steve. I’m going to turn around now, as I’m sure we have some great questions from the floor. Who has the first question then?

Q….. from your point of view especially, your experience in the investment banking world — what concrete measures do you think they should be doing to combat, prevent this phenomenon? We know that various sums of money are used in all sorts of ways and they do have different initiatives, but in order to concretely counter this epidemic now, what are your thoughts?

“For Christians, and particularly for those who believe in the underpinnings of the Judeo-Christian West, I don’t believe that we should have a [financial] bailout.”

Bannon: That’s a great question. The 2008 crisis, I think the financial crisis — which, by the way, I don’t think we’ve come through — is really driven I believe by the greed, much of it driven by the greed of the investment banks. My old firm, Goldman Sachs — traditionally the best banks are leveraged 8:1. When we had the financial crisis in 2008, the investment banks were leveraged 35:1. Those rules had specifically been changed by a guy named Hank Paulson. He was secretary of Treasury. As chairman of Goldman Sachs, he had gone to Washington years before and asked for those changes. That made the banks not really investment banks, but made them hedge funds — and highly susceptible to changes in liquidity. And so the crisis of 2008 was, quite frankly, really never recovered from in the United States. It’s one of the reasons last quarter you saw 2.9% negative growth in a quarter. So the United States economy is in very, very tough shape.

And one of the reasons is that we’ve never really gone and dug down and sorted through the problems of 2008. Particularly the fact — think about it — not one criminal charge has ever been brought to any bank executive associated with 2008 crisis. And in fact, it gets worse. No bonuses and none of their equity was taken. So part of the prime drivers of the wealth that they took in the 15 years leading up to the crisis was not hit at all, and I think that’s one of the fuels of this populist revolt that we’re seeing as the tea party. So I think there are many, many measures, particularly about getting the banks on better footing, making them address all the liquid assets they have. I think you need a real clean-up of the banks balance sheets.

……

Questioner: Thank you.

Bannon: Great question.

Questioner: Hello, Mr. Bannon. I’m Mario Fantini, a Vermonter living in Vienna, Austria. You began describing some of the trends you’re seeing worldwide, very dangerous trends, worry trends. Another movement that I’ve been seeing grow and spread in Europe, unfortunately, is what can only be described as tribalist or neo-nativist movement — they call themselves Identitarians. These are mostly young, working-class, populist groups, and they’re teaching self-defense classes, but also they are arguing against — and quite effectively, I might add — against capitalism and global financial institutions, etc. How do we counteract this stuff? Because they’re appealing to a lot of young people at a very visceral level, especially with the ethnic and racial stuff.

Bannon: I didn’t hear the whole question, about the tribalist?

Questioner: Very simply put, there’s a growing movement among young people here in Europe, in France and in Austria and elsewhere, and they’re arguing very effectively against Wall Street institutions and they’re also appealing to people on an ethnic and racial level. And I was just wondering what you would recommend to counteract these movements, which are growing.

Bannon: One of the reasons that you can understand how they’re being fueled is that they’re not seeing the benefits of capitalism. I mean particularly — and I think it’s particularly more advanced in Europe than it is in the United States, but in the United States it’s getting pretty advanced — is that when you have this kind of crony capitalism, you have a different set of rules for the people that make the rules. It’s this partnership of big government and corporatists. I think it starts to fuel, particularly as you start to see negative job creation. If you go back, in fact, and look at the United States’ GDP, you look at a bunch of Europe. If you take out government spending, you know, we’ve had negative growth on a real basis for over a decade.

And that all trickles down to the man in the street. If you look at people’s lives, and particularly millennials, look at people under 30 — people under 30, there’s 50% really under employment of people in the United States, which is probably the most advanced economy in the West, and it gets worse in Europe.

…..

And that’s what I think is fueling this populist revolt. Whether that revolt is in the midlands of England, or whether it’s in Middle America. And I think people are fed up with it.

And I think that’s why you’re seeing — when you read the media says, “tea party is losing, losing elections,” that is all BS. The elections we don’t win, we’re forcing those crony capitalists to come and admit that they’re not going to do this again. The whole narrative in Washington has been changed by this populist revolt that we call the grassroots of the tea party movement.

And it’s specifically because those bailouts were completely and totally unfair. It didn’t make those financial institutions any stronger, and it bailed out a bunch of people — by the way, and these are people that have all gone to Yale, and Harvard, they went to the finest institutions in the West. They should have known better.

And by the way: It’s all the institutions of the accounting firms, the law firms, the investment banks, the consulting firms, the elite of the elite, the educated elite, they understood what they were getting into, forcibly took all the benefits from it and then look to the government, went hat in hand to the government to be bailed out. And they’ve never been held accountable today. Trust me — they are going to be held accountable. You’re seeing this populist movement called the tea party in the United States.

“I certainly think secularism has sapped the strength of the Judeo-Christian West to defend its ideals, right?”

….

Bannon: Could you summarize that for me?

Harnwell: The first question was, you’d reference the Front National and UKIP as having elements that are tinged with the racial aspect amidst their voter profile, and the questioner was asking how you intend to deal with that aspect.

Bannon: I don’t believe I said UKIP in that. I was really talking about the parties on the continent, Front National and other European parties.

I’m not an expert in this, but it seems that they have had some aspects that may be anti-Semitic or racial. By the way, even in the tea party, we have a broad movement like this, and we’ve been criticized, and they try to make the tea party as being racist, etc., which it’s not. But there’s always elements who turn up at these things, whether it’s militia guys or whatever. Some that are fringe organizations. My point is that over time it all gets kind of washed out, right? People understand what pulls them together, and the people on the margins I think get marginalized more and more.

I believe that you’ll see this in the center-right populist movement in continental Europe. I’ve spent quite a bit of time with UKIP, and I can say to you that I’ve never seen anything at all with UKIP that even comes close to that. I think they’ve done a very good job of policing themselves to really make sure that people including the British National Front and others were not included in the party, and I think you’ve seen that also with tea party groups, where some people would show up and were kind of marginal members of the tea party, and the tea party did a great job of policing themselves early on. And I think that’s why when you hear charges of racism against the tea party, it doesn’t stick with the American people, because they really understand.

I think when you look at any kind of revolution — and this is a revolution — you always have some groups that are disparate. I think that will all burn away over time and you’ll see more of a mainstream center-right populist movement.

“Because at the end of the day, I think that Putin and his cronies are really a kleptocracy, that are really an imperialist power that want to expand.”

Question: Obviously, before the European elections the two parties had a clear link to Putin. If one of the representatives of the dangers of capitalism is the state involvement in capitalism, so, I see there, also Marine Le Pen campaigning in Moscow with Putin, and also UKIP strongly defending Russian positions in geopolitical terms.

….

Bannon: I think it’s a little bit more complicated. When Vladimir Putin, when you really look at some of the underpinnings of some of his beliefs today, a lot of those come from what I call Eurasianism; he’s got an adviser who harkens back to Julius Evola and different writers of the early 20th century who are really the supporters of what’s called the traditionalist movement, which really eventually metastasized into Italian fascism. A lot of people that are traditionalists are attracted to that.

One of the reasons is that they believe that at least Putin is standing up for traditional institutions, and he’s trying to do it in a form of nationalism — and I think that people, particularly in certain countries, want to see the sovereignty for their country, they want to see nationalism for their country. They don’t believe in this kind of pan-European Union or they don’t believe in the centralized government in the United States. They’d rather see more of a states-based entity that the founders originally set up where freedoms were controlled at the local level.

…..

I’m not justifying Vladimir Putin and the kleptocracy that he represents, because he eventually is the state capitalist of kleptocracy. However, we the Judeo-Christian West really have to look at what he’s talking about as far as traditionalism goes — particularly the sense of where it supports the underpinnings of nationalism — and I happen to think that the individual sovereignty of a country is a good thing and a strong thing. I think strong countries and strong nationalist movements in countries make strong neighbors, and that is really the building blocks that built Western Europe and the United States, and I think it’s what can see us forward.

You know, Putin’s been quite an interesting character. He’s also very, very, very intelligent. I can see this in the United States where he’s playing very strongly to social conservatives about his message about more traditional values, so I think it’s something that we have to be very much on guard of. Because at the end of the day, I think that Putin and his cronies are really a kleptocracy, that are really an imperialist power that want to expand. However, I really believe that in this current environment, where you’re facing a potential new caliphate that is very aggressive that is really a situation — I’m not saying we can put it on a back burner — but I think we have to deal with first things first.

Questioner: One of my questions has to do with how the West should be responding to radical Islam. How, specifically, should we as the West respond to Jihadism without losing our own soul? Because we can win the war and lose ourselves at the same time. How should the West respond to radical Islam and not lose itself in the process?

Bannon: From a perspective — this may be a little more militant than others. I think definitely you’re going to need an aspect that is [unintelligible]. I believe you should take a very, very, very aggressive stance against radical Islam. And I realize there are other aspects that are not as militant and not as aggressive and that’s fine.

If you look back at the long history of the Judeo-Christian West struggle against Islam, I believe that our forefathers kept their stance, and I think they did the right thing. I think they kept it out of the world, whether it was at Vienna, or Tours, or other places… It bequeathed to use the great institution that is the church of the West.

….

Because it is a crisis, and it’s not going away. You don’t have to take my word for it. All you have to do is read the news every day, see what’s coming up, see what they’re putting on Twitter, what they’re putting on Facebook, see what’s on CNN, what’s on BBC. See what’s happening, and you will see we’re in a war of immense proportions. It’s very easy to play to our baser instincts, and we can’t do that. But our forefathers didn’t do it either. And they were able to stave this off, and they were able to defeat it, and they were able to bequeath to us a church and a civilization that really is the flower of mankind, so I think it’s incumbent on all of us to do what I call a gut check, to really think about what our role is in this battle that’s before us.