(A few additional comments added on 02/21/21)

COVID-19 is still a menace that is affecting thousands of people every day across the globe. However, vaccination and palliative therapies indicate that there is less of it ahead of us than behind us. I am training in pathology at a hospital in Texas and do not have the required qualifications to talk about the nitty gritty of COVID virus and its structure. However, I was involved in management of patients with COVID who were in intensive care and before that, in procuring convalescent plasma for COVID patients. I want to write about the policy and public health side of managing COVID and not the clinical perspective, which is not my primary specialty. This piece was inspired by two articles in the New Yorker, the first is a long-read from Lawrence Wright (here) and the second is from Charles Duhigg (here).

When news about COVID started trickling at the end of December 2019, I was not alarmed. I thought of SARS, Swine flu, Ebola and MERS, which were mostly containable viral diseases and their human impact was not global. I was at a conference in Dallas at the end of January, where a presentation was on memories of dealing with the first Ebola case in the US. I remember sitting in the back row of the auditorium and listening to the lengths that a particular hospital in Dallas went, to quarantine the said Ebola patient. By February, there was news of how Chinese state was hiding things about the mysterious viral infection and whistleblowers were shedding more light on the disease. It was in late January-early February that first cases of the mystery virus were discovered in Seattle suburbs and suppression of data/news about COVID started in the US (the Trump administration). I was at another conference in Los Angeles at the end of February and saw the news that cases of COVID had been diagnosed near San Francisco.

Upon my return to work in the first week of March, I was required by the hospital to report travel to the employee health clinic, which I did. Prior to arrival of COVID, I was going to travel to Ohio for an elective rotation and to New York to present at a conference. With COVID, all plans had to be cancelled. Since March of last year, COVID has affected millions of people across the globe and disrupted life as it used to be. One of my friends refers to any year before 2020 as “X years B.C.” (before COVID). Moving from my personal story to a bird’s eye view, what can we learn from COVID moving forward? I have tried to distill my thoughts about the pandemic, pandemic response and best practices.

Based on what we know now, here are a few things about COVID response, with relevant exceptions:

1. Island nations have generally done better, with exception of Britain and to an extent, Vietnam. At the start of the pandemic, there were fears that autocratic governments will prevail better because dictators don’t have to worry about human rights, laws or courts. That fear has not come true, generally. Australia, New Zealand, Taiwan, Sri Lanka or Vietnam are mostly democratic nations.

2. Things have been better when scientists and public health officials have been allowed to be at the forefront, except in the case of Sweden, where the top epidemiologist wanted to test his “herd immunity” theory. The New Yorker story from Charles Duhigg that I mention above, refers to a significant difference in COVID cases and deaths between New York, where politicians were at the forefront of COVID response, versus Washington state, where public health officials made the rules.

3. African nations have done better at managing COVID than most ‘first-world’ countries, in my opinion, due to their experience in dealing with Ebola, MERS and similar viral illnesses. There has been a recent second wave and a South-African variant that is more resistance to the mRNA vaccines than the OG COVID-19 or the UK variant. There was a recent story in the BBC about the second wave (here) and earlier, about the low rates of infection and mortality in the African continent (here).

4. It is incredibly hard to restrict what constitutes “daily life” even in the face of a deadly pandemic. Human beings are social animals and severing that connection from others, whether in form of closing offices or bars and restaurants, cannot be reliably depended on for long periods. Travel has become another necessity in this day and age, for business or pleasure. Airlines and the hospitality industry as a whole will be running losses for years to come. I traveled three times during the last year, twice domestically and once on an international route. I tried to be cautious and got tested before/after each of these journeys, which, admittedly is not a perfect way of being safe from COVID. There were multiple studies about spread of COVID on airplanes and I was constantly in fear of contracting it while flying, despite all precautionary measures.

I do not frequent bars/clubs in general so i didn’t miss them much. However, I did miss spending time at the library and our nearby Barnes and Noble. If one were to look at the graphs of cases and deaths in the US, there are peaks around memorial day, 4th of July, Labor day, Halloween, Thanksgiving, Christmas and New Year. Around Christmas, close to a million people were flying every day in the U.S. Graphics from the Washington Post tracker.

5. China, not completely culpable but deserves blame for its early missteps and obfuscation (a la Great leap forward) when it comes to COVID. We still don’t know if COVID transmission started at a wet market or somewhere else. Wuhan is back to pre-COVID times while the rest of world keeps suffering. Chinese authorities have tried to strong arm the WHO and any outside effort to investigate the origin of transmission of COVID. I do not subscribe to the conspiracy theory that COVID is a “China virus” or that it was manufactured in a Chinese laboratory.

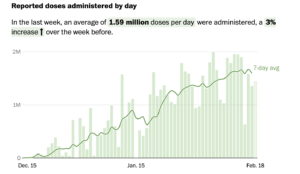

6. Vaccines. I consider the development of COVID vaccines a modern day miracle. The fastest that a vaccine had been previously prepared was close to three years. The severity of disease, mounting death rate and irresponsible behavior by the general public, made the timeline for introduction of a vaccine shorter than ever. Fortunately, the mRNA type platform vaccines had been in development for years and this was the right moment for them. The journey started in January 2020, when COVID genome was first shared by Chinese scientists and culminated in November/December 2020, when two major candidate vaccines was ready to be administered. Since mid-December, more than 73 million doses of either of these vaccines has been distributed in the US. This is a graphic from the Washington Post tracking vaccine distribution in the US:

I got vaccinated in January and feel fortunate to have that immunity. However, the mRNA vaccines have a 66% response to the South-African variant (versus 90-95% against the OG COVID). The AstraZeneca vaccine has a 23% immune response to the South African variant. There is very little good data on vaccines developed by Russia, China and India. From what we know about their mechanisms of action, Russian vaccine is similar in mechanism to the AstraZeneca vaccine (uses inactivated Adenovirus), while the Chinese vaccine is based on inactivated virus and the Indian (serum institute version) uses live attenuated virus. Graphic from NEJM.

7. Viruses don’t care about state or national boundaries. The Sturgis motorcycle rally in South Dakota in August led to increased cases in neighboring Minnesota (here). A single conference in Boston in Feb 2020 lead to almost 300,000 cases (here). COVID has reached Antarctica, the last bastion of human presence without infection (here).

8. Disinformation spreads faster than the truth. The famous line that “A lie can travel halfway around the world before the truth can get its boots on” was truer during the COVID pandemic than any other modern peacetime event. Since I have a medical degree and had some exposure to COVID response, I was asked by many family members and friends from across the globe about various conspiracy theories circulating regarding COVID. The top hits included COVID vaccine altering your DNA, different cocktails for treating COVID (the whole hydroxychloroquine debacle), herd immunity, exaggerated vaccine side effects, masks, Vitamin D, COVID vs Flu, PCR vs rapid testing and their predictive values, various miracle cures etc. Many of these lies and misinformed views were spearheaded by medical personnel (doctors, nurses, nurse practitioners etc) which made it incredibly hard for a layperson to know what was the truth and what was just a fanciful conspiracy theory. To top it all off, many people initially (and still) refuse to believe that COVID is real.

9. Masks work but not all masks are the same. This is related to point 4 from earlier (human nature cannot be suppressed for long). It is hard to wear a mask all the time. I work at the hospital and that being a high-risk area, everyone has to be masked almost all the time. But, due to strict masking requirement, infection rate of workers (both medical and non-medical) at our hospital stayed less than 1% even when the infection rate was close to 10% in the community that we serve. N95s which should be worn by individuals who are at the highest risk of getting COVID provide better protection than a regular surgical mask (efficacy close to 65%), which is better than a regular cloth mask (efficacy less than 50% and needs to be washed regularly). I have seen innumerable number of people wearing their masks incorrectly (i.e. nose not covered) but I think that at least they are wearing a mask. One reason that east asian nations did better at controlling the pandemic is because mask-wearing is normalized at a larger societal level, compared to “freedom from tyranny” type attitudes seen in the US. According to estimates, if 90% people in the US had worn masks at the beginning of COVID, we could have averted millions of cases and thousands of deaths.

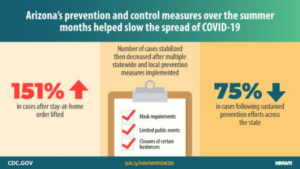

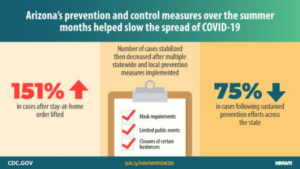

In Arizona, there were dramatic improvements in case numbers once mask mandates were enforced. (paper from CDC here).

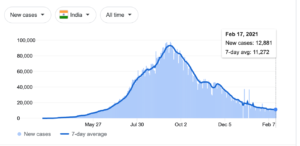

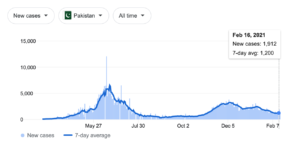

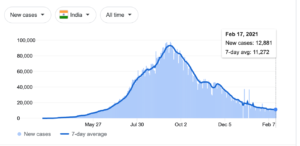

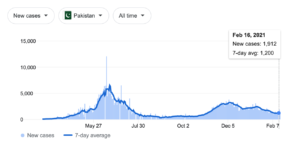

10. The curious case of Pakistan and India. Early in the pandemic, while COVID was running rampant through most of Europe, North America and South America, India and Pakistan had very few cases compared to their populations. While India has caught up with the rest of the world lately, Pakistan is still reporting less cases than any major city in the US per day. What is causing this divergence? There are many theories and until it is studied methodically, I don’t have a clear answer. Even people who got COVID in Pakistan, got a mild disease. Many people pointed to BCG vaccination as being semi-protective against COVID. Some commentators proposed immunity due to earlier sub-clinical viral infections. Are there genetic factors causing this? My hypothesis is that Pakistan is not as exposed to the outside world as lets say the United States is. Secondly, testing in Pakistan is at a much lower level than anywhere else. At one point last year, the state of Punjab, with a population larger than Germany, was doing close to 15,000 COVID tests a day. If you don’t test, you can’t diagnose. Cases in Pakistan and India, graphs from the Johns Hopkins dashboard.

11.Personal Responsibility. The mantra of personal responsibility has been used throughout the pandemic by mostly right-wing politicians, trying to avert blame from themselves, resulting in a terrible failure. Anyone who has ever worked in customer relations can tell you that most people don’t really care about other people (knowingly or unknowingly). Public health does not work that way. One can argue that even economics doesn’t work that way either, but that is a separate debate.

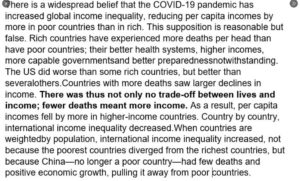

12. One heard the phrase “how many lives can you save by closing the economy” or variations of it since the early days of the pandemic. The lives versus economy rubric was debated over and over, without much evidence. Countries in the EU and Australia/NZ paid people to stay home. That approach is paying them off in the long run. In a paper titled “COVID-19 and global income equality” (here), Angus Deaton showed that saving lives has a positive impact on long-term economic outlook of a country.

13. Is the “office space” dead? Are we going to have a different economy after the pandemic? Would there be mass migration from major cities towards smaller towns and suburbs? I don’t have these answers as I am not an economist or a public planner. But these questions interest me and I am always trying to read about them.

14. Lastly, I cannot predict what is going to happen with COVID. When the pandemic started, my hope was that it would die down within six months. With a sharp decline in case numbers and increase in vaccinated individuals, I have hope that COVID would be under control by the end of the year. Would new variants disrupt this timeline and everyone will have to get a booster vaccine at some point in time? It is quite likely.

Comments and suggestions welcome!