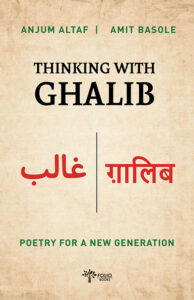

Publisher: Folio Books

Publishing date: 2021

Authors: Anjum Altaf & Amit Basole

“For Ghalib, life is an unending search. Neither the holy of holies in Mecca nor even the attainment of paradise is the end of it.” ~Ralph Russell

We’ve all heard of that crooked genius, Mirza Asadullah Beg Khan Ghalib — whether through our school Urdu courses (unfortunately encountered at an age when our consciousness is still unripe) or through pop culture. Sometimes it’s his well-known fantasy for mangoes; other times it’s when someone shares a couplet whose slightly convoluted vocabulary immediately earns it the label of “a Ghalib shayr”; and other times, his destitution and scrambling for a pension.

As a Gen Z myself, I can say that most of today’s youth are largely alienated from the Urdu language, let alone Persian. And of course, this doesn’t mean we’re reading Byron or Eliot instead; rather, it’s the excess of TikTok. Decoding Ghalib feels like a Herculean task for us. This dilemma not only distances us from a rich poetic tradition but also from the timeless lessons it has nurtured.

On the one hand, the images Ghalib evokes are diverse, his vocabulary inventive, and his flow strikingly unconventional. Both the syntax and semantics of his poetry are nothing short of astonishing. For readers like me, whose reading habits are mostly in English and whose command over Urdu (and Farsi, entirely) is modest, this means we’re deprived of fully savoring the beauty of Ghalib’s expression.

Enter “Thinking with Ghalib”, co-authored by Anjum Altaf and Amit Basole. While I’m unfamiliar with the latter beyond this book, I can tell you that Anjum Altaf is an animated personality. Like me, he hails from Peshawar and has served as Dean at LUMS. Beyond that, he’s fond of “transcreating” great poets — from Shakespeare and Faiz to Meeraji and Eliot — on his Substack blog, and he also contributes to a national newspaper.

Before talking about the book in itself, the context of this book matters personally. I came across it after finishing my intermediate studies, during a period of waiting before my higher education began. Given Ghalib’s stature and notorious inaccessibility, even after trying to read him through the widely used exegesis “Gufta e Ghalib” by Prof. Hameed Ullah Shah Hashmi, I still couldn’t fully penetrate his subtext and applicability to the current aeon. Then I stumbled upon this book online, and I bought and devoured it at once.

It was like opening a window into the enigmatic kaleidoscope of this big-time poet. It changed my perspective of Ghalib; firstly, the authors translated/transcreated the couplets in a very convenient and smooth manner, and secondly, they worked as iconoclasts to prevailing propensities, as I had subscribed to the common notion of him being obsessed with themes of longing, love, yearning, and whatnot. The learning was so robust that even after many years, I always refer to this book, whenever I quote Ghalib in English. See an example here.

My predilections were shattered by a very “epistemological” reading of his poetry, where both authors would cherry-pick a couplet and then expand it to universal realms: what we can learn and unlearn, how it unspools the sociopolitical climate, how not to absorb -isms without critique, the modus operandi of political scaffolds, and everything that cannot be easily reduced to a legacy Gothic interpretation.

For instance, while reading the shayr, “laazim nahii kih Khizr kii ham pai-ravii kare/ jaana kih ik buzurg hame ham-safar mile” (trans: It is not necessary that we follow in the footsteps of Khizr/We consider that we have a venerable elder as a fellow-traveller); they write:

Another instance of an exquisite epistemological reading of the couplet: “az mihr ta bah-zarrah dil-o-dil hai aaiinah/tuutii ko shash jihat se muqaabil hai aaiinah” (trans: From sun to sand-grain all are hearts and the heart is a mirror/ The parrot is confronted from all six directions by a mirror); they write:

“Everything is made of sand (atoms) and every grain of sand is like a heart (here the imagery lends beauty to the words – the sun and sand-grains shimmer and seem to pulsate like a heart); and every heart is a mirror. Thus, the learner (parrot/poet/human) is completely surrounded by mirrors and sees its own reflection everywhere… Good learning is crucially dependent on the accuracy of the reflection of reality. And this, in turn, is crucially dependent on the faithfulness of the mirror. We can understand the faithfulness of the mirror in two respects: the sincerity of the learner (here the mirror is the heart) and the accuracy of information that surrounds the learner (here the mirror is what surrounds us).”

This book is a book of hope, especially during these times when the subcontinent’s multicultural, multireligious civilisation is threatened by so many forces from so many sides. Just look at the Pahalgam attack spree. Both sides are hating each other without any introspection, without gauging the consequences of such inhumanity; we are missing the macrocosmic minds.

We lack the rebellious voices grounded in reality — minds like Ghalib’s. he penned “kyuu nah chiikhuu kih yaad karte hai miri aavaaz gar nahii aati” (trans: Why would I not scream because I am remembered/Only when my voice is not heard). And presto, it is the hot moment to interpret and reinterpret his genius into simple, plain English. I would recommend this book to everyone, especially enthu-cutlets who, like myself, may lack mastery over Urdu or Farsi, or maybe don’t know Urdu at all, but still carry the zeal to engage with the great poet of the subcontinent — through an interdisciplinary lens and in plain English, with minimal loss of translation magic.

Also, a poem I wrote a while back where Ghalib is mentioned. Let me share:

moon is not mine

For thy sweet love remembered such wealth brings

That then I scorn to change my state with kings. [1]

Heavenly and haply, I thought in sun,

When dissonance hugged in tense.

Raven tress I saw in Ghalib’s mirror,

And my heart pulsated with screeching stress.

And in spite of the intimacy of anxiety,

I thought of thy gaudy anatomy and shadows,

With every curve that cascades.

I fancy and long for your smell;

I want to feel your insides, ungodly entanglements,

fill your small mouth with your favourite ice cream,

And write love songs again and again,

Without bootless cries and infinite vigor and rigor,

I tramp on the labor of love.

You inflated my life,

Jalebis and gulab jamuns were taste-less,

flowers were smell-less,

and rainbow body-less.

The waist that every deer urges for,

The colours every phoenix dies for,

The face every hedonist lives for.

I want to consume and to be consumed,

To and to be adorned,

To and to be desired.

Gauge my sinister mind,

What I yearn for.

[1] Sonnet 29 by Shakespeare

Just want to state that the two authors never met each other in person. This whole book was written on Zoom. It actually started out years earlier as a collaboration between their two blogs. So it’s a great example of cross-border collaboration.

there are efforts to write Urdu in Hindi script. This might make Urdu poetry accessible to a larger Indian audience.

Yes. This book has each couplet written in Nastaliq, Devnagari and roman as well as a translation.