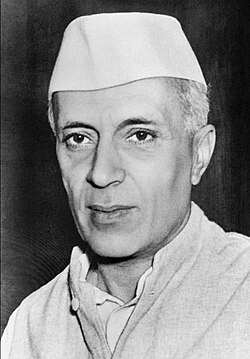

Kabir’s defence of Nehru as the moral compass of the Indian republic reveals something deeper than nostalgia for secularism. It exposes how much of India’s founding moment was shaped by a single man whose class background insulated him from the material and psychological stakes of Partition; stakes that Gandhi, Jinnah, Bose, Ambedkar, and even Savarkar understood far more viscerally.

Nehru was unique among the major players of his era. He was the only one born into national leadership, the only one who inherited a political position, and the only one whose life had been marked not by struggle but by access. While others were shaped by jail, exile, poverty, or ideological intensity, Nehru was shaped by privilege, and privilege has its own blind spots.

This matters because 1947 was not a moment for abstract idealism. It was a moment for negotiation between communities whose elites no longer trusted one another. On that task, Nehru was the least prepared of the principal actors.

I. Nehru’s Privilege Was a Constraint, Not a Qualification

Consider the backgrounds that shaped India’s other leaders:

Jinnah spent decades as a Congress-League bridge-builder before communal politics forced him to choose sides. His 1916 Lucknow Pact showed he could deliver Muslim elites to a Hindu-majority compromise. By 1940, he had concluded such compromises were impossible; not from theology but from experience.

Bose built the Forward Bloc by organizing Bengal’s bhadralok and courting Japan during war. Whether this was strategic brilliance or desperation, it proved he understood that power flows from organized force, not moral argument.

Ambedkar negotiated the Poona Pact with Gandhi in 1932 while recovering from communal award trauma. He knew what it meant to extract terms from a stronger party. His drafting of the Constitution reflects that education: rights matter only when enforceable.

Savarkar spent a decade in Cellular Jail writing Hindutva in isolation. Prison clarifies priorities. His vision of Hindu consolidation, however complex its later mutations, emerged from direct confrontation with powerlessness.

Gandhi fasted in Noakhali while Hindus and Muslims slaughtered each other in 1946. He walked through villages others fled. His authority came from proximity to suffering, not distance from it.

And then there was Nehru, whose political education came through:

- Harrow and Cambridge (1905–1912)

- His father’s law practice and Congress presidency

- European socialism read in translation

- A Kashmiri Pandit ancestry that gave him Brahminical prestige without caste anxiety

- Friendships with Mountbatten, Edwina, and the Fabian literati

The result: he imagined India not as it was, but as it ought to be; according to codes drawn from the world he inhabited. This was not malice. It was miscalibration.

II. The Cabinet Mission Plan: A Test Case

In May 1946, the British Cabinet Mission proposed a federation that would keep India united while granting provinces autonomy in three groups:

- Group A (Hindu-majority)

- Group B (Punjab, NWFP, Sindh)

- Group C (Bengal, Assam)

Jinnah accepted it. The League passed a resolution on June 6, 1946. Nehru rejected the grouping formula at his July 10 press conference in Bombay, declaring that Congress was “completely unfettered by agreements” and would enter the Constituent Assembly “free to meet all situations as they arise.”

Wavell wrote in his diary: “Nehru’s press conference has driven a coach and horses through the whole plan.”

Why did Nehru do this? Not because the plan was unworkable, Patel thought it salvageable, and Azad had brokered it, but because Nehru found the very logic of group-based representation distasteful. It offended his belief that individuals, not communities, should be the unit of politics. This was an idealist’s error at a tactician’s moment.

The collapse of the Cabinet Mission Plan made Partition inevitable. What followed was the Calcutta killings (August 1946), the Noakhali riots (October 1946), and the Bihar retaliation (November 1946). The violence Nehru’s scruples wanted to avoid became certain because he refused the compromise that might have contained it.

III. What the Other Leaders Saw That Nehru Could Not

Jinnah understood that Muslim elites feared losing position in a Hindu-majority democracy. This wasn’t paranoia; it was arithmetic. In UP, the Muslim League won all 30 reserved seats in 1946, but Congress formed the government. Jinnah concluded: Muslims can win every seat marked for them and still be locked out of power. Nehru’s response? He called this “communal thinking” and insisted that secular parties represented everyone.

Ambedkar understood that constitutional language means nothing without enforcement. In his 1945 book Pakistan or the Partition of India, he wrote: “The Hindus and Muslims of India are not likely to be able to evolve a common will… under a democratic system.” He saw that the problem was structural, not rhetorical. Nehru’s response? He wrote a review calling Ambedkar’s analysis “defeatist.”

Bose understood that the state is built on organized power, not shared sentiment. His INA trials in 1945–46 showed that spectacle and force can shift mass opinion faster than argument. When Congress defended INA prisoners, it wasn’t because of secular principle; it was because Hindu and Muslim soldiers had fought together, and that unity had strategic value. Nehru supported the INA defendants, but only as a moral gesture, not as a template for politics.

Savarkar understood Hindu insecurity even if his solution was unworkable. In Essentials of Hindutva (1923), he had written: “We Hindus are bound together not only by common holy places but also by the dream of a Sanskritic Fatherland.” This wasn’t theology; it was an answer to the question: what holds a majority together when that majority is fragmented by caste? Nehru’s response? He treated Hindu assertion as reactionary rather than as a political fact requiring management.

IV. A Man of Ideals in a Moment of Hard Choices

Kabir quotes Nehru as if quoting scripture. But Nehru’s greatest weakness was the belief that ideals could substitute for settlements.

He gave India:

- A soaring speech at midnight on August 15, 1947

- A secular grammar embedded in constitutional preamble

- A flattering self-image as heir to a civilizational tradition

What he did not give India:

- A clear compact with the Muslim minority that remained after Partition

- A framework for Hindu majoritarianism that could be held within democratic bounds

- A power-sharing formula that reflected demographic realities

- A system to absorb the shock of 10 million refugees and 1 million dead

A state cannot be built on emotion alone. And 1947 was not the moment for sentiment. The irony is that Nehru’s ideals constrained him exactly because they came from privilege. Men shaped by scarcity learn compromise. Men shaped by entitlement assume harmony.

V. The Counterfactual: What a Real Strategist Would Have Done

Imagine if the head of Congress in the 1940s had been Patel rather than Nehru; someone who understood coalition-building, organizational discipline, and bargaining under pressure.

The likely outcomes:

Option 1: Negotiated Symmetry A federal India with three autonomous regions and a weak center. This was essentially the Cabinet Mission Plan. It would have required Congress accepting limits on central power but it would have kept India united and given Muslim elites provincial authority. It may have eventually led to a Velvet Divorce in the manner of Czechoslovakia but it wouldn’t have been so poisoned by religious sectarianism.

Option 2: Clean Partition If unity was impossible, then Partition should have been surgical: population exchanges negotiated in advance, borders drawn with geographic logic, property rights clarified. Turkey and Greece managed this in 1923. Germany and Poland after 1945. Painful, but clear. What India got instead was Nehru’s romantic half-measure:

- Part unity

- Part rupture

- No settlement

- No clarity

The ambiguity killed a million people and displaced ten million more. And India is still living inside that ambiguity today; every debate over Kashmir, every riot over conversion, every controversy over the Babri Masjid is an aftershock of the settlement that never happened.

VI. Jinnah, Bose, Savarkar, and the Elite Civil War

Partition was not a Hindu–Muslim war fought by peasants. It was an elite civil war fought over the terms of succession.

Jinnah represented Muslim elites who feared permanent minority status in a democracy. His demand for Pakistan was not theological; it was transactional. He wanted a separate state where Ashrafs could remain dominant, rather than risk losing position in Hindu-majority India.

Bose represented a modern mass nationalism that could incorporate Hindu symbols without becoming sectarian. His vision failed not because it was incoherent, but because he died before he could implement it.

Savarkar represented Hindu elites trying to forge a majority identity across caste lines. His project was always fragile, Brahmins and Marathas had little in common, but he understood the problem: a majority that doesn’t cohere will lose to a minority that does.

Nehru represented none of these constituencies.

He represented a narrow Kashmiri Pandit aristocracy with a universalist style that masked how distant he was from the anxieties of ordinary Hindus and Muslims. His fluency in English socialist discourse gave him international prestige but domestic blindness. As observed by Granville Austin: Nehru’s Congress was “a coalition of the elite talking to itself.”

The Congress’ dominance reflected in elections to the Constituent Assembly, which was aptly described by Granville Austin as a ‘one party body’ in a ‘one party country’: ‘The Assembly was the Congress and the Congress was India’.

VII. The Blind Spot: Nehru Could Not See the Muslim Question

The tragedy of Nehru’s leadership is that he could not comprehend the depth of Muslim political grievance not because he was anti-Muslim, but because he lacked proximity to Muslim life.

His closest Muslim associates were people like Azad: Deobandi scholars fluent in Urdu high culture, comfortable in Congress, and equally distant from the anxieties of Bihari weavers or UP farmers who feared economic displacement.

Nehru never understood:

- Why UP Ashrafs preferred Jinnah’s Pakistan to Congress’s secularism

- Why rural Muslims saw Hindu economic dominance as existential

- Why Pakistan had emotional pull even for Muslims who would never migrate

- Why the League’s 1946 electoral landslide was a mandate, not a mistake

It was the blindness of a man who had never been “othered.”

As a result:

- He dismissed Muslim suspicion as “communalism”

- He dismissed Hindu insecurity as “reactionary”

- He dismissed the League’s victories as an aberration

- He assumed that secular language would dissolve structural mistrust

This was not leadership. It was misdiagnosis. And misdiagnosis at a founding moment becomes pathology.

VIII. Mountbatten and Nehru: A Partnership of Misfits

It is no accident that Nehru’s closest political partner in 1947 was Mountbatten; a man elevated by royal birth rather than military brilliance.

Both shared:

- Aristocratic charm

- A talent for speeches

- Little instinct for organizational detail

- Enormous confidence without corresponding evidence

Together they presided over the most consequential political transfer in modern history with remarkable carelessness:

- Borders announced two days after independence

- Radcliffe working from outdated maps

- No preparation for mass migration

- No security cordon for mixed districts

- No plan for Kashmir

Two aristocrats trying to solve a civilizational fracture with pageantry and rhetoric. The cost was borne by millions. Churchill’s judgment of Mountbatten, “a man of immense charm and no judgment“, applies equally to Nehru in 1947.

IX. What Kabir’s Defence of Nehru Reveals

Kabir idolizes Nehru because Kabir himself comes from elite continuity, global liberal education, and urban cosmopolitanism. Nehru is the perfect avatar for that class:

- Urbane

- Articulate

- Idealistic

- Insulated from the harsh edges of society

But 1947 was not a moment for moral comfort. It was a moment for clarity. Nehru provided language. He did not provide structure. India inherited the consequences:

- A Muslim minority without a renewed compact

- A Hindu majority without a defined project

- A bureaucracy that preserved colonial hierarchy

- A constitutional system that promised rights without power to enforce them

Kabir is right to admire Nehru’s words. But words were the problem. Nehru gave India ideals when what it needed was terms.

X. Conclusion: The Surgeon Who Never Made the Incision

India needed a tactician in 1947. It got a patrician. India needed a negotiator. It got a rhetorician. India needed someone who could think like the masses. It got someone who thought like an Edwardian aristocrat. The result was an India that inherited:

- Partition without clarity

- Unity without settlement

- Secularism without structure

- Democracy without the coalitions to sustain it

The tragedy of 1947 is not only that Partition happened. It is that India was led through its deepest crisis by a man whose privileges made him incapable of seeing how dangerous ambiguity can be. Nehru’s admirers celebrate him for keeping India united and democratic. This is half true. India remained united because Patel managed the states and Ambedkar wrote the Constitution. It remained democratic because the British had already built those institutions.

What Nehru left unfinished was the political settlement; the compact between communities, the terms of majority rule, the framework for minority security. The wound remains open because the surgeon never made the incision. And seventy-five years later, India is still bleeding from 1947.

I agree with you that Pandit Nehru’s rejection of the Cabinet Mission Plan (after initially accepting it) was a huge mistake and squandering of the last chance to keep India united. I have never argued that he was perfect. Among other things, he had a huge ego and his personal friction with QeA is probably a large part of why Partition happened.

Also, I feel that you are being a bit unfair to Nehru by judging him solely on Partition. He was PM of India for nearly two decades afterwards and managed to set it on a secular, democratic path. He was a leader of the non-aligned movement.

In the end, I philosophically prefer Pandit Nehru’s belief in a secular democratic state for all its citizens to QeA’s “Two Nation Theory”–which is inherently an exclusionary idea. It is deeply ironic that one of the few things that the Hindu Right and Pakistanis agree on is that Hindus and Muslims cannot live together in one nation-state.

Before anyone accuses me of hypocrisy, I will just point out that I’m a Pakistani simply because I was born there and because my parents were born there. This is the result of my grandfathers’ choices not those of myself or my parents (both of whom were born after Partition).

I think Nehru had a very grandiose vision for India but a practical one may have made India a 20k usd per capita nation now..

Modi seems to have been a boon for the Indian economy

Nehru was a socialist (which of course you are free to disagree with).

I believe the Indian economy really took off under Narasimha Rao (when Manmohan Singh was Finance Minister iirc)

UPA had much better growth in every aspect from 2004-14. did you have chance to look into data. India has huge under employment. people in agriculture sector has increased during Modi while it decreased by 15% during UPA time. Private investment is very low during Modi while it was great during UPA.

the nominal growth is low during Modi while real GDP number look nice because they fudge the inflation data and show the inflation very low. please check it out.. but anyways you are what you are..

I am what I am 🙂

yes I don’t know what to say about Indian growth story.. it would be good to have posts on that.

Welcome to Brown Pundits!

This seems relevant:

“Purushottam Agrawal & Harsh Mander on why RSS hates Nehru, and more”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-0qrJfdTW0k

You should know better than to take a grifter like Mander seriously.

Mander?