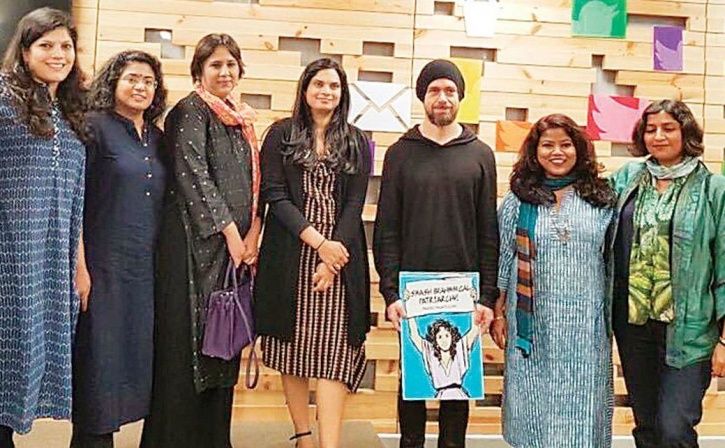

In December 2018, Jack Dorsey had a photo-op with a section Indian feminists (left-leaning) holding a placard that read Smash Brahmanical Patriarchy. Naturally, Hindutva supporters took umbrage to the reduction of Patriarchy in India to Brahmanism & “supposed” targetting of Brahmins. The “Liberals” appeared consistent with their ideological framework, though the framework can be accused of being myopic. Here are some essays from both sides of the ideological spectrum – Wire & Swarajya.

When words become labels, they tend to deviate from their original meaning and end up serving just their political purpose. The word Brahmanical is in danger of becoming a catch-all term on the left to not just to attack Hindutva but also to indulge in some masochism. Like all terms in Hinduism, Brahminism is difficult to define. For the purpose of this essay, I would refer to all Hindu practices & rituals which have a basis in scriptures like the Vedic Canon, Puranas/Itihasa, Sutras/Shastras as Brahmanism. (I would welcome any better definition of Brahmanism. It is often easier to negate a Hindu practice as Non-Brahmanical than the other way around)

Similarly, the word Patriarchy is likewise used loosely as an amalgamation of the words patriarchy, misogyny, sexism, and male chauvinism. Patriarchy is a hallmark of human civilization, especially post the agricultural revolution. Just a handful of cultures have been exceptional. As a result, all strands of patriarchy in a society cannot be blamed on the predominant religious current of the culture unless there is a logical & direct link between the two – correlation is not causation. Coming to India lets focus on the different strands of Patriarchy present in the country and try to entangle each strand and investigate its potential origins in Brahmanism.

MARRIAGE

In Brahmanism, marriage is a sacred bond between man and woman(women) and hence unbreakable. As polygamy is allowed under Brahmanism, Men could move on to newer women without breaking the sacred bond and continue to lead a Dharmic life. Women had a lot of patriarchal restrictions placed on them. It is interesting to note that the Hindu marriage act of 1955 has transformed Hindu marriage customs in Hinduism. Hence wrt Marriage – Smashing Brahmanism would be equal to beating a dead ARYA horse in 21st century India. All these strands of “patriarchy” exist to almost the same extent in other native India “Panthas” in -Buddhism, Jainism, Sikhism. No need to explain how Muslim personal law is way worse wrt marriage today and needs immediate attention from Feminists.

INHERITANCE

Brahmanism did not support the rights of women to inherit property, but the 1956 act meant that equal inheritance rights were awarded. On the other hand, Muslim women don’t get equal rights under Muslim personal law.

WIDOWS

The conditions of widows in Brahmanism was arguably worse than most other cultures. With Remarriage out of question (unlike Islam and Christianity), widows were treated inhumanely in Hinduism – especially in Brahmanical orthodoxy. The Brahmanical obsession with abstract concepts of purity and consequent “bad luck” blamed on the widow meant that widows were sentenced to social boycott in Hindu societies (social murder). The other option – Sati is also uniquely Brahmanical. (though its prevalence in olden times is debated). Even today, widow remarriage is less common than widower remarriage. A lot of regression and inhuman attitude towards widows continue to this day even among elite and liberal Hindus. Hence wrt Widows Brahmanical Patriarchy is still alive and needs SMASHING.

Eg: Widows are still considered inauspicious. Even today a widow cannot predominantly partake Brahmanical rituals on her own, she always needs a male/couple (pure and auspicious) helping hand/s to carry out rituals. Typically Marriage/Upanayana/other rituals are carried out by the Uncles of her children. Though Hindu society has moved beyond the Social ostracization of earlier times, the position of widows is far from equal.

Having said that, the overlap of these practices with Varna oppression isn’t wide. These practices are particular to the Dvija Varnas. Conditions of widows in subaltern castes & tribes were historically significantly better – with remarriage/separation allowed in many subaltern/tribal communities.

DOWRY

It is difficult to pin down the custom of Dowry on Brahmanism. By accounts of most experts, it is a sociological custom not unique to India.

FEMALE FOETICIDE

A Direct consequence of Dowry and Two child policy (along with economic hardships and some other factors) Female Foeticide – arguably the worst Anti-Female practice in India is also a deeply sociological practice with very tenuous or no links to “Religions”. (Though Christianity actively condemns all abortions and hence Female Foeticide has no existence in Christians)

RELIGIOUS ROLE OF WOMEN

All religions present in India are deeply sexist and Brahmanism (Hinduism) doesn’t stand out as a particularly bad. However, the impurity attributed to menstruation is directly an outgrowth of the Brahmanical obsession of ritualistic purity. From practices of untouchability for menstruating women to the temple entry conflict, these customs can be attributed to Brahmanism though other faiths aren’t doing a particularly great job. Even Buddha’s teachings and the role of women in Buddhist Sangha are not remotely equal. However, the position of women in a lot of Brahmanical rituals is secondary/inferior to men. One could make a logical argument from Brahmanism to the demoted the role of women in rituals. (same as other faiths)

Sabrimala – though people claim the issue in Sabrimala is due to the Celibacy of Lord Ayyappa & not ritual taboo of menstruation- the priests of Sabrimala carried out a purification ritual after the women visited Sabrimala.

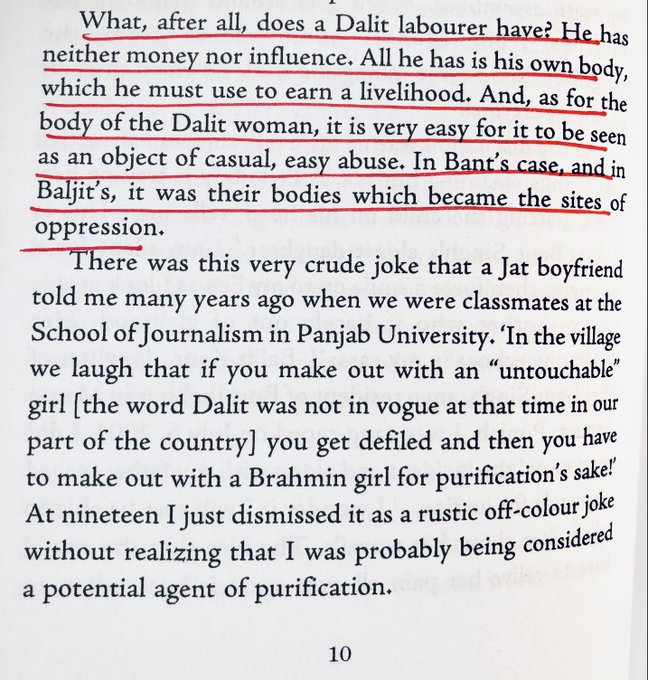

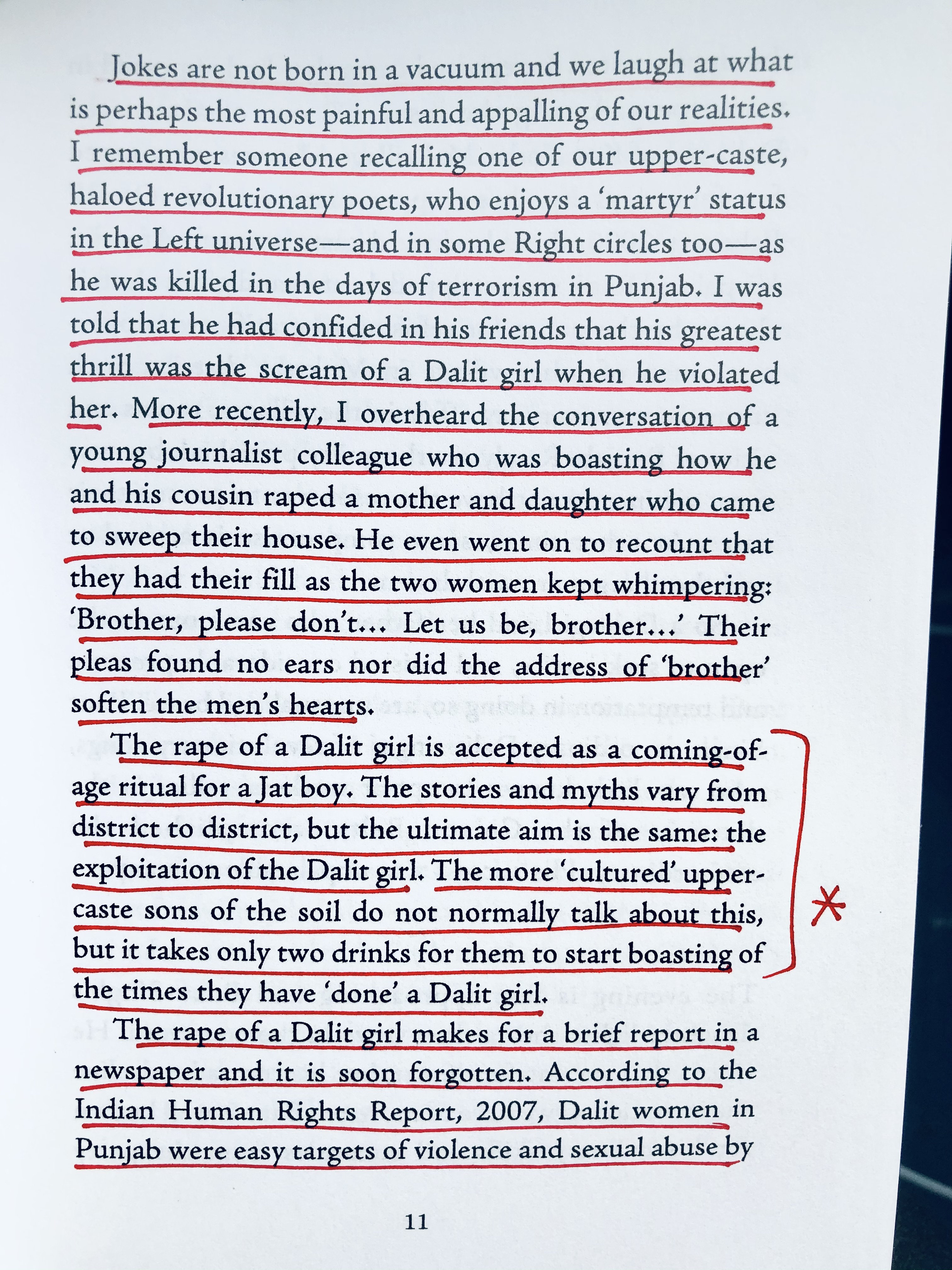

SEXUAL VIOLENCE

No correlation. This problem is worse in India than some regions of the world but no coherent link between this and Brahmanism exists.

CASUAL SEXISM & MISOGYNY

Is a universal societal problem. There is an argument that some aspects this is an overreaction to the overreach of some aspects of feminism (from conservative POV- I don’t hold this view)

ENDOGAMY

While caste endogamy is often blamed on Brahmanical doctrines – and especially the notorious Manusmriti, on a deeper investigation of the texts, the link is found to be not very robust. While the DIKTATS against the mixing of Varnas is a very important part of Manusmriti (and other texts too), the jati endogamy practice in India doesn’t have many sanctions in Brahmanical texts. Getting deep into the nuances around Jati and Varna is beyond the scope of this essay. Given the fact that Varna is a salient feature of Brahmanism and Jati is an outgrowth of Varna in a sense, we can logically argue that the origins of Endogamy are Brahmanical.

However its sustenance in 21st century India is due to tribalism, pressures of families (larger caste groups) and Compatibility correlated with Jati.

HONOR CULTURE

Honor culture is a salient part of most caste conflicts in the country, but given the preponderance of similar conflicts in other cultures (Islamic), this practice cant be blamed on Brahmanism.

CHILD MARRIAGE

The universal practice in medieval and early modern times. On the contrary Vedic canon advises post-puberty marriage for both sexes.

EDUCATION AND OTHER FREEDOMS

Like most religions wrt education and other freedoms, Brahmanism was harsh on women. But it doesn’t stand out. Even though subaltern women faced harsh Brahmanical opposition (Like Savitri Phule), the same is true for upper-caste women reformers as well. Sub Altern women faced the double combo of Brahmanical Casteism and Patriarchy, hence the blame of this strand can be put mildly on Brahmanism wrt Christianity but not wrt other faiths.

MODESTY (PURDAH)

Practiced in North Indian Hindu cultures, but most experts believe these practices were imposed on women after Islamic Turko-Afghan invasions of 11th century.

There may be some more strands of “Patriarchy” in India which are not covered here.

Out of the 13 strands identified above a modest 5 practices can be partially blamed on Brahmanism. Even out of these 5, 2 are addressed legally and are inconsequential today with 3/13 Brahmanical strands remaining (though these aren’t the biggest problems for 21st century India). If the aim is to Smash All Patriarchy – smashing Brahmanical Patriarchy which achieves only a fraction of the aim, can’t logically be the primary objective. In other words, wrt Feminism in India there are bigger fish to fry.

Some have argued that “Brahmanical patriarchy is a conceptual framework” that has a wider meaning. But it has been a word (Brahmanism) which means something specific for almost over a century and its definition was never as broad or loose as Hinduism.

Another issue I had with the “Smash Brahmanical Patriarchy” was the lack of understanding in the general population of the term Brahmanism. Any political point being made has value only if it resonates with the masses for whom it is coined. That certainly doesn’t seem to be the case here. As a result, such a sloganeering can be viewed by a considerable population as bigotry against Brahmins (As lots of people pointed out). Having said that, had the slogan been analytically watertight it wouldn’t matter IMO.

Next time there is ideological virtue-signaling – let us hope there is robust elucidation instead of attack with language meant as a catch-all for what one opposes. (Like calling your opponent fascists)

Ironically brahmin communities (mostly due to early exposure to education) are some of the least patriarchal communities of the country. Most women wouldn’t mind freedoms enjoyed by women in these communities (especially MH and WB). Though this would be explained as Brahmanical patriarchy which aims to oppress Bahujan women while emancipating Savarna ones. An incredibly contrived discussion arguing this can be found here with which I

profoundly disagree – but that argument is for some other time.