This deliberately provocative piece draws on Kabir’s recent comments, Arkacanda’s excellent essay, Musings on & Answers, and Nikhil’s profound piece in “Urdu: An Indian Language.”

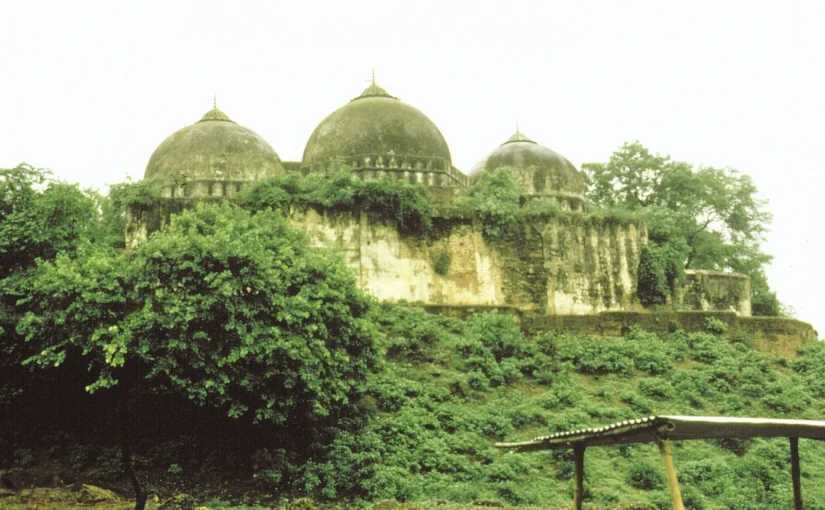

If India wants to avoid future Babri Masjids, it needs a clearer, more orderly doctrine for handling irreconcilable sacred disputes. Excavation, relocation, and compensation should be formalised as the default tools, rather than allowing conflicts to metastasise into civilisational crises. Geography matters. Some sites carry layered sanctity for multiple traditions; others do not. Al-Aqsa, for instance, is both the site of the Jewish Temple and central to Islamic sacred history through the Isra and Miʿraj. Babri Masjid was not comparable. It had no unique pan-Islamic significance, while the site was widely regarded within Hindu tradition as the birthplace of Lord Ram. The same logic applies to Mathura, associated with Lord Krishna. Recognising asymmetry of sacred weight is not prejudice; it is common sense. A rules-based system—full archaeological excavation, dignified relocation of structures where necessary, and generous compensation—would allow India to preserve heritage without endlessly reopening civilisational wounds.

Urdu is not an Indian language but Hindu nationalists made it one

It is a Muslim-inspired language that emerged in India. That distinction matters. Blurring it creates confusion, not harmony. There was an early misstep in North Indian language politics. Modern Hindi was deliberately standardised on Khari Boli rather than on Braj Bhasha or Awadhi, both of which possessed far richer literary lineages. This decision, shaped by colonial administrative needs and North Indian elite nationalism, flattened a complex linguistic ecology and hardened later divides. One unintended consequence was the permanent preservation of Urdu within the Indian subcontinent. Because Khari Boli Hindi remained structurally interchangeable with Urdu, Urdu survived as a parallel high language. Had Braj or Awadhi become the standard instead, that mutual intelligibility would have collapsed, and Urdu would likely have been pushed entirely outside the Indian linguistic sphere.

Persian Linguistic Pride

Today, a similar impulse is at work. There is a growing tendency, often well intentioned, to Indianise the Mughals and Urdu, to fold them into a seamless civilisational story. This misunderstands both history and the settlement that Partition produced. Partition did not merely redraw borders. It separated elites, languages, and political destinies. Urdu crossed that line with Muslim nationalism. It cannot now be reclaimed without ignoring that choice. I say this as someone with both an Urdu-speaking and Persian-speaking inheritance. When I chose which tradition to consciously relearn and deepen, I chose Persian. Not out of sentiment, but judgment. Persian language nationalism remains rigorous, self-confident, and civilisationally anchored. Persian survived empire, exile, and modernity without losing coherence. It carries philosophy, poetry, statecraft, and metaphysics as a single, continuous tradition. Shi‘ism, Persianate culture, and Persian literature remain intertwined. They preserve depth rather than dilute it. As a Bahá’í, that continuity has personal resonance. But the argument does not depend on belief. It stands on history.

Urdu as the “Muslim tongue” Continue reading Should Babri Masjid have been moved to Pakistan?