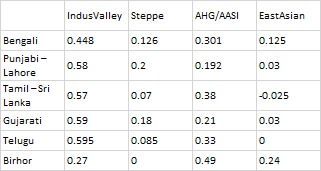

A recent WhatsApp exchange between GL and Sbarr captures a recurring Brown Pundits problem: how genetic data, textual tradition, and social history get collapsed into a single argument and then talk past one another. The immediate trigger was a table circulating online, showing ancestry proportions across South Asian groups; Indus Valley–related, Steppe, AASI, and East Asian components. The numbers vary by region and language group. None support purity. None map cleanly onto caste. That much is uncontroversial. What followed was not a dispute about the data itself, but about what kind of claims the data can bear.

GL’s Position (Summarised)

GL’s argument operates at three levels: historical, linguistic, and genetic.

-

Caste as fluid history

GL argues that the four-fold varna system hardened late. Terms like Vaishya did not always mean “merchant” but originally derived from viś—“the people.” In this reading, Vaishya once referred broadly to non-priestly, non-warrior populations, including farmers and artisans.

-

Elite religion thesis

Early Śramaṇa movements, Buddhists, Jains, Ajivikas, are framed as elite projects. Renunciation, non-violence, and philosophical inquiry required surplus. Most people, GL argues, worshipped local deities and lived outside these doctrinal systems.

-

Genes as complexity, not identity

GL points out that Steppe ancestry and Y-DNA lineages are unevenly distributed. Some peasant groups show higher Steppe ancestry than some Brahmin groups. Maternal lines are largely local. The conclusion is not reclassification, but complication: caste cannot be reverse-engineered from genes. GL’s underlying claim is modest: simple caste narratives do not survive contact with deep history.

Sbarr’s Position (Summarised)

Sbarr’s objections are structural and definitional.

-

Varna as stable social fact

In lived Hindu society, Vaishya has meant merchant since at least the Dharmashastra period. Etymology does not override usage. Peasants were not Vaishyas. Shudras worked the land. Dalits lay outside the system.

-

South Indian specificity

Sbarr stresses that the North Indian varna model does not transplant cleanly into the Tamil world, where Brahmins, non-Brahmin literati, Jain monks, and Buddhist authors all contributed to classical literature. Claims of universal Brahmin authorship are rejected.

-

Genes do not make caste

Even if some peasant or tribal groups show Steppe Y-DNA, this does not make them Brahmins or twice-born. Genetic percentages are low, overlapping, and socially meaningless without institutions.

Sbarr’s core concern is different from GL’s: the danger of dissolving concrete social history into abstract theory.

Where the Debate Breaks Down

The argument falters because the two sides are answering different questions.

-

GL is asking: How did these categories emerge over millennia?

-

Sbarr is asking: How did people actually live, identify, and reproduce hierarchy?

Genes describe populations. Texts describe ideals. Caste describes power. None substitute for the others.

The Takeaway (Without a Verdict)

The ancestry table does not refute caste. The Manusmriti does not explain population genetics. Etymology does not override social practice. What the exchange shows, usefully, is the limit of WhatsApp as a medium for longue-durée history. Complex systems resist compression. When they are forced into slogans, everyone ends up defending a position they did not fully intend. That, more than Steppe percentages or varna theory, is the real lesson here.