This deliberately provocative piece draws on Kabir’s recent comments, Arkacanda’s excellent essay, Musings on & Answers, and Nikhil’s profound piece in “Urdu: An Indian Language.”

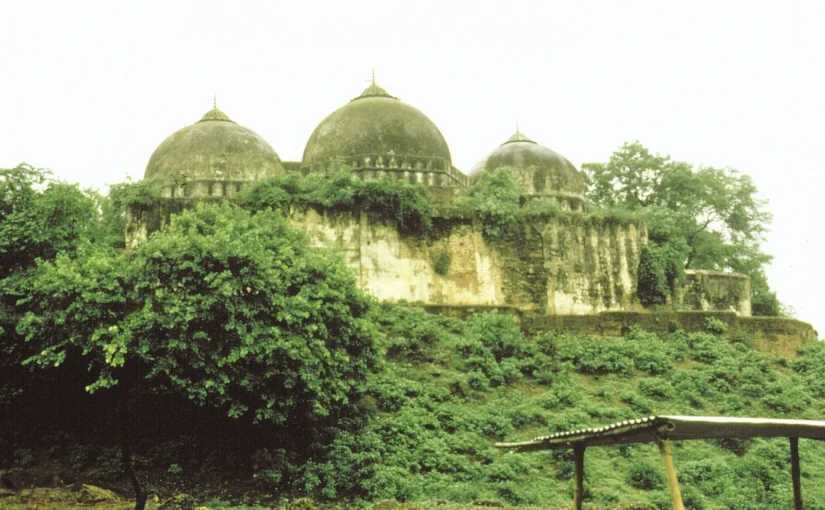

If India wants to avoid future Babri Masjids, it needs a clearer, more orderly doctrine for handling irreconcilable sacred disputes. Excavation, relocation, and compensation should be formalised as the default tools, rather than allowing conflicts to metastasise into civilisational crises. Geography matters. Some sites carry layered sanctity for multiple traditions; others do not. Al-Aqsa, for instance, is both the site of the Jewish Temple and central to Islamic sacred history through the Isra and Miʿraj. Babri Masjid was not comparable. It had no unique pan-Islamic significance, while the site was widely regarded within Hindu tradition as the birthplace of Lord Ram. The same logic applies to Mathura, associated with Lord Krishna. Recognising asymmetry of sacred weight is not prejudice; it is common sense. A rules-based system—full archaeological excavation, dignified relocation of structures where necessary, and generous compensation—would allow India to preserve heritage without endlessly reopening civilisational wounds.

Urdu is not an Indian language but Hindu nationalists made it one

It is a Muslim-inspired language that emerged in India. That distinction matters. Blurring it creates confusion, not harmony. There was an early misstep in North Indian language politics. Modern Hindi was deliberately standardised on Khari Boli rather than on Braj Bhasha or Awadhi, both of which possessed far richer literary lineages. This decision, shaped by colonial administrative needs and North Indian elite nationalism, flattened a complex linguistic ecology and hardened later divides. One unintended consequence was the permanent preservation of Urdu within the Indian subcontinent. Because Khari Boli Hindi remained structurally interchangeable with Urdu, Urdu survived as a parallel high language. Had Braj or Awadhi become the standard instead, that mutual intelligibility would have collapsed, and Urdu would likely have been pushed entirely outside the Indian linguistic sphere.

Persian Linguistic Pride

Today, a similar impulse is at work. There is a growing tendency, often well intentioned, to Indianise the Mughals and Urdu, to fold them into a seamless civilisational story. This misunderstands both history and the settlement that Partition produced. Partition did not merely redraw borders. It separated elites, languages, and political destinies. Urdu crossed that line with Muslim nationalism. It cannot now be reclaimed without ignoring that choice. I say this as someone with both an Urdu-speaking and Persian-speaking inheritance. When I chose which tradition to consciously relearn and deepen, I chose Persian. Not out of sentiment, but judgment. Persian language nationalism remains rigorous, self-confident, and civilisationally anchored. Persian survived empire, exile, and modernity without losing coherence. It carries philosophy, poetry, statecraft, and metaphysics as a single, continuous tradition. Shi‘ism, Persianate culture, and Persian literature remain intertwined. They preserve depth rather than dilute it. As a Bahá’í, that continuity has personal resonance. But the argument does not depend on belief. It stands on history.

Urdu as the “Muslim tongue”

Urdu, by contrast, has become overly compromised by modern Muslim nationalism. Its literary and cultural confidence increasingly depends on political grievance rather than civilisational self-possession. That does not make it illegitimate but it does make it different. Treating Urdu as simply “another Indian language” obscures this reality and ultimately weakens both the language and the civilisations it straddles. Recognising difference honestly is not an act of exclusion; it is the precondition for intellectual clarity.

Urdu After Partition

Partition did one decisive thing: it separated elites. India retained a Hindu civilisational core with Muslim minorities. Pakistan became the political home of Islamicate culture in the subcontinent. That division was tragic, but it was also final. After 1947, Urdu ceased to be a shared elite language. It became even more Islamicisized. This was not an accident. It was the outcome of Muslim political nationalism itself. The foremost Urdu poet of the twentieth century, Allama Iqbal, argued explicitly that Hindus and Muslims were separate nations and required separate political futures. Whatever one thinks of his conclusions, his authority on Urdu cannot be dismissed. If the leading voice of the language insisted that Urdu required a Muslim political home, then it is incoherent to later claim Urdu as a neutral Indian inheritance. You cannot reject the politics and keep the prestige.

Indian Muslims and the Post-Partition Reality

Partition did not just divide territory; it reshaped elites. Indian Muslim elites may exist in number, but they are largely Hindu-fied in outlook, habit, and public expression. They operate comfortably within a Hindu civilisational framework and rarely articulate an autonomous Islamicate political vision. This mirrors the reverse dynamic in Pakistan, where non-Muslim elites are often highly integrated precisely because they adopt the assumptions and reforms of a Muslim nation-state. Elite integration follows power, not sentiment. This is why post-Partition arguments that demand India suspend its civilisational gravity indefinitely are unrealistic. Civilisations absorb; minorities adapt; elites align. That is not moral failure; it is how history stabilises itself. Partition resolved this question structurally. This places Indian Muslims closer to Christians than to Sikhs, Jains, or Buddhists. Like most Christians outside Kerala, they are shaped by empire and global circuits, not by control of the national symbolic centre.

Indianisation Is Also Hinduisation

There is another uncomfortable truth: when Islamicate forms are “Indianised”, they are also Hindufied. This is not unique to India. In the West, cultures are routinely whitened and universalised. Power always absorbs difference into its own frame. Hindustani music, Mughal aesthetics, Urdu poetry, when preserved in India, are curated, softened, and reframed through a Dharmic lens. They survive, but as heritage, not as sovereign traditions. Again, this is not cruelty. It is how major civilisations behave.

Architecture, Curation, and a Missed Opportunity

India’s architectural inheritance is staggering. Any serious observer knows this. In Britain, a five-hundred-year-old structure, like Babri Masjid, is a Grade I listed monument. In India, structures of comparable age are often trapped in political deadlock or administrative neglect. There are pragmatic solutions that nobody wants to discuss. Where sites are irreconcilably contested, full archaeological excavation followed by relocation is not sacrilege; it is preservation. Museums and relocated monuments already exist across the world. The problem is not resources. It is imagination. India has not yet learned how to curate itself at civilisational scale.

Language Loss in Pakistan

Partition also produced an irony across the border. In Pakistan, Urdu was elevated as the national language, but Punjabi, the majority language, was marginalised. With the exception of Sindh, regional languages were subordinated to an alien Urdu unity. Punjabi survives largely, in a prestige form, because Sikhs preserved it (and they have made Punjabi culture & rap, sexy across the Indian Subcontinent). Among Muslims and Hindus, it receded. This was not a triumph of Urdu; it was a loss of linguistic plurality. Nationalism always extracts a price.

The Inescapable Conclusion

India today is Bharat. Its national song is Vande Mataram. Its civilisational logic is Dharmic. Even its secularism operates through Hindu habits of absorption rather than exclusion. Everything is accepted, slowly transformed, and rendered local. This is not a slide into extremism. It is the long arc of history asserting itself. Those who lament this should remember: this outcome is the logic of Partition. Bangladesh chose a Bengali Muslim identity. Pakistan chose an Islamicate one. India chose to remain civilisationally Hindu with minorities inside it. That choice was not imposed. It was inherited.

A Final Thought

I would have had far more respect for Urdu nationalism if it had been honest about its implications. You cannot argue for separation and then demand custodianship of the shared past. History does not work that way. India has the right, earned through survival, to curate its past on its own terms. That curation will be Hindu in texture, plural in accommodation, and unapologetic in centre of gravity. This is not erasure. It is settlement. And it is long overdue.

India is constitutionally a secular state. Indian law states that places of worship are supposed to be left as they were on August 15, 1947. Thus, according to the law the Babri Masjid should still be standing. The destruction of a minority place of worship is never acceptable in a secular state.

Urdu is an Indian language. Its historical heartland was Delhi, Agra and Lucknow. The fact that the entity to India’s west made Urdu its national language cannot change geographical and historic facts. As Nikhil pointed out in his essay, one of Urdu’s great poets Firaq Gorakhpuri was born Raghupati Sahay. Languages do not belong to particular religions.

It is deeply sad that Urdu in India is increasingly being treated as the language of the “other”. This is a-historical and just reveals an extremist mindset.

Yes but the law is malleable. I am simply saying in the case of the Mathura Masjid; it might be better to follow the excavate, relocate, compensate model.

Of course, laws can be changed.

I think Babri should be treated as an exception. Going down this path of getting rid of mosques is not acceptable in a constitutionally secular state.

Something similar happened with the Somnath temple in Gujarat soon after partition. There was a masjid in the ruins of the Somnath temple. Through dialogue, rather than mob violence, the Somnath temple was reclaimed.

I remember on Twitter seeing an Iranian Muslim man ranting about Hindu extremism and the destruction of masjids, but upon better understanding the scope of the demands (Mathura, Kashi, Ayodhya) and the relative significance of the sites to the two religions and the abundance of other masjids in India, became rather perplexed that this was such a big issue. If these are their holiest sites and they are few in number and it’s clear (especially so in the case of Mathura and Kashi) that they were destroyed and repurposed, just hand it over and resolve the issue. Build goodwill.

On the other hand, one could argue that appeasement never works, and that this could just encourage more requests.

I think dialogue could have addressed these issues, but now views have become hardened. I think Western liberals have made it worse, by treating any such temple reclamation as further evidence of Muslim persecution in India.

I have read in some site that Urdu is considered as zabaan-e-deen. this is what Hindus see Urdu as ,Moonot withstanding a firaq there or a gulzar here.

Yes Urdu was a language pretty much invented by Indians & Hindus as it stands to communicate with Turko-Persians

Like most great food is the food of the poor. Urdu definitely didn’t have elite beginnings

The “father of Urdu” is considered to be Hazrat Amir Khusrao. He was definitely not a Hindu. His father was Turkic and his mother was “Indian” (not that that term makes sense because no nation-state of India existed).

@formerly brown: Urdu as the “zabaan-e-deen” is nonsense. Urdu is the language of UP. It’s a language associated with a particular geography. It is not owned by a particular religion.

Indian at that time was probably a couple of generations removed from Hindu?

Sorry, I’m going to be annoying about this and say that it is a-historic to call pre-modern people “Indian”. It’s a meaningless concept.

Amir Khusrao’s mother was named Bibi Daulat Naz. Her father was Rawat Arz who was the war minister of Ghiyas ud-Din Balban. So presumably his mother’s family had been Muslims for at least two generations.

Munshi Premchand is considered to be a pioneer of Urdu social fiction. His real name was Dhanpat Rai Srivastava.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Premchand

I think it is very problematic to associate languages with particular religions. Urdu is the language of UP. It’s a different matter that post 1947, many Urdu speakers would now probably identify themselves as Hindi speakers. Anyway, except at the literary levels, the real difference between Hindi and Urdu is the script.

babari masjid was and gyanvapi masjid of kashi is an ugly building, hastily built just to show power over infidels.

if you see the remnants ( extremely ornate wall ) of the shiva temple which was destroyed, one can marvel at the grandeur of the temple.

having seen these buildings which were efforts of natives, one can safely conclude that architects of taj and jumma masjid of delhi were ‘ foreiginers’.

Heritage is not about the aesthetics but the age as well.