This post by X.T.M has brought up some important points that Indians (and, by extension, Hindus) need to wrestle with. The author’s foundational hypothesis is that “India’s central trauma is not diversity. It is Partition.”

I don’t think I’ve ever read such a succinct diagnosis trying to get to the root of India’s issues, much less such a novel one (at least to me). For these reasons, if nothing else, I think X.T.M’s idea merits a deeper look.

I am largely in agreement with the author that diversity in and of itself is not at the heart of India’s troubles if only because it seems to have always been a factor in Indian society for as far back as we have history. Indeed, “diversity” and differentiation seem to me to be a mark of the continuity of Indian civilization from the earliest days of our forefathers. If this, our patrimonial diversity, has become a bane to India, it is to the India that plays at being a modern nation-state, democracy, and republic — not to the India of uncountable Gods, saints, and heroes, each at the heart of their world, ruling over the innumerable hamlets that dot the country and the uncountable kindreds that dwell within them. As Diana Eck (2012) puts it: “The profusion of divine manifestation is played in multiple keys as the natural counterpart of divine infinity, incapable of being limited to any name or form, and therefore expressible only through multiplication and plurality.” (India: A Sacred Geography, p. 48).

It is the second half of the author’s initial hypothesis that I think is the most important bit to dissect. Something about this diagnosis does not strike me as entirely accurate.

It is true that Partition split the Indian folk, namely, Hindus and Muslims, but the shape that this split took is a rather curious and, at least for me, unexpected one. According to the Pew Research Center’s June 29, 2021 report titled Religion in India: Tolerance and Segregation (Sahgal et al.), when asked whether Partition was a good or a bad thing for Hindu-Muslim relations in a 2019 survey, 43% of Indian Hindus saw it as good while 37% of them saw it as bad. Indian Muslims? Quite the opposite. Only a third (30%) of them saw it as helping communal relations while almost half (48%) saw it as actually harmful.

While Partition may have been the bloody birth pangs of the Indian State and been a very real source of deep pain to the actual humans affected by it, what ails the folks of India is, I think, altogether something else. As to what exactly this is, I will come back to it towards the end of this essay.

X.T.M’s second hypothesis is something I actually agree with. such as the idea that the “two peoples” (Hindus and Muslims) could have lived together. We have seen time and time again that incomers to India have, over time, flowed into the great folksea that ebbs and flows upon our lands like trickles of glacial melt joining with the ocean, at once both one and sundry.

There is data to support this as well. In the same Pew report I cited above (Sehgal et al., 2021), the researchers found that while both Hindus and Muslims wish for segregation in their personal lives, as can be seen in the high percentage (over two-thirds) of both groups who want to stop intermarriage, the fact that most Indians’ friends tend to be from their own religious communities, and 45% of Hindus would not want a neighbour from at least one of the other major religions (Hindu, Sikh, Jain, Buddhist, Muslim, & Christian) — a figure matched by 36% of Muslims, when it comes to what folks believe, there seems to be a surprising degree of similarity that crosses religious lines. The report revealed that an equal percentage of Indian Muslims believed in karma as did Indian Hindus (77%), along with over half of Indian Christians (54%), two-thirds of Buddhists and Sikhs, and 75% of Jains. Around one-third of Muslims and Christians said they believed in reincarnation as opposed to (and I found this very weird) only 40% of Hindus, 18% of Buddhists and Sikhs, and 23% of Jains). A similar level of belief in the purifying power of the Ganga was found among the two Abrahamic faiths. Needless to say that none of these ideas could be considered orthodox doctrine in any tradition of Islam or Christianity, and any adherence to them by followers of those religions in India immediately opens up a flood of questions one could ask.

Could it be the result of a superimposition of a Muslim or Christian layer onto a Hindu-Buddhist base such as happens when a linguistic superstrate is built atop a conquered population leading to the adoption of vocabulary and grammatical features from the linguistic substrate? Or, could it be like the speculated spread of retroflex consonants, which, while found in languages in many parts of the world, are particularly concentrated in India? Perhaps it’s a consequence of Hindu demographic domination over the last several decades causing it to serve as a sort of ‘prestige dialect’ among Indian religions? In any case, I don’t think we can discount the probability that a generally convivial attitude between Hindus and Muslims could have been maintained prior to Partition.

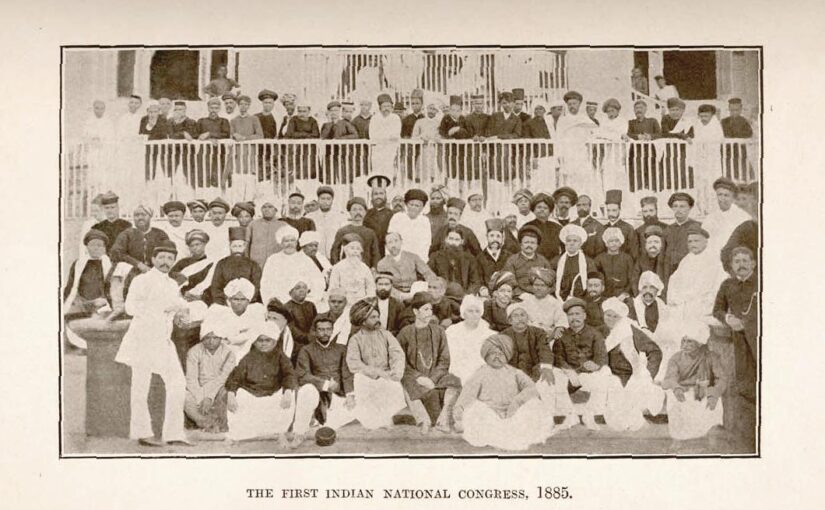

As such, I am generally in agreement with X.T.M’s argument that what happened was largely because of the will of the political elite. What I do take issue with is the rather ludicrous oversimplification of the so-called ‘Hindu’ side as the “Brahminical–Congress elite”, not only because it is patently untrue in terms of the actual people who led the Congress. Let’s take a look at some of the founding and early members. There are: Continue reading Musings on & Answers to “The Partition of Elites: India, Pakistan, and the Unfinished Trauma of 1947” (Part 1)