In the rankings of major Indian states based on per capita income, UP and Bihar have been occupying the last two places for quite a while. Their per capita incomes are approximately half and one third of the national average, which has sparked considerable discussion lately. While most people focus on usual suspects like overpopulation and corruption, some argue that the absence of coastlines also plays a significant role. This idea has appeared in this blog several times, and I will offer my two cents.

On the surface, the argument seems reasonable, given that both Bihar and UP are non-coastal states and many coastal states are doing extremely well. However, a closer look reveals a lack of empirical evidence to support this claim. To begin with, the correlation between higher per capita income and having a coastline is relatively new. Back in 1990, of the eight major coastal states, only Maharashtra was performing exceptionally well. Gujarat was above average, while Karnataka, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, and Bengal were either average or slightly below. Orissa, on the other hand, was quite poor. This suggests that it was economic liberalization, rather than the mere presence of coastlines, that primarily fueled the growth in South India.

The correlation between coastal status and economic performance appears even more spurious when we examine other non-coastal states. There are eight large non-coastal states with populations exceeding 20 million, excluding UP and Bihar. Their combined per capita income is almost same as the national average. In fact, two of these states, Telangana and Haryana, rank among the top three. If being landlocked is indeed such a significant disadvantage, why doesn’t it similarly impact these other non-coastal states?

Let’s explore the coastline related industries further. India’s blue economy, which includes sectors like coastal tourism, fisheries, shipping, and offshore energy, constitutes only about 4 percent of the country’s GDP. Given that coastal states account for 55 percent of India’s GDP, it’s evident that coastlines aren’t as impactful economically as one might assume. The transport sector in India represents roughly 5 percent of the GDP, but a significant part of this involves passenger and local freight transport. The part consisting of transport between port and non-coastal states is relatively small, and the extra burden is equivalent to a tax of less than 5 percent on all imported or exported goods.

So one could probably argue that if UP and Bihar were coastal, their per capita incomes might be 5-10 percent higher. However, this doesn’t change the big picture.

Why Do BJP and Narendra Modi Keep Winning? Why Do Congress and Rahul Gandhi Keep Losing?

Why do BJP and Narendra Modi keep winning? Why do Congress and Rahul Gandhi keep losing?: Yogendra Yadav, National Convenor, Bharat Jodo Abhiyan, a former political analyst & psephologist, answers in an interview to Karan Thapar

Also adding this video (in Hindi):

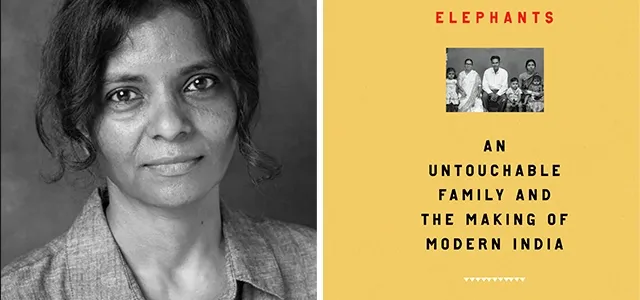

Ants Among Elephants: A Portrait of Untouchability in India

Since we are discussing caste, this post from my Substack seems relevant. This review was originally published on “The South Asian Idea” in January 2018.

One of the frequent topics of debate among those interested in South Asia is the caste system and whether it is unique to Hinduism or features in other South Asian religions as well. Hindu society has traditionally been divided into four castes (or varnas): Brahmins (priests), Kshatriyas (rulers, administrators and warriors), Vaishyas (merchants and tradesmen), and Shudras (artisans, farmers and laboring classes). A fifth group consists of those who do not fit into this hierarchy at all and are considered “untouchable”. What separates caste from other systems of social stratification are the aspects of purity and ascribed status. Upper-castes consider lower castes to be “impure” and have rigid rules about the kind of social interaction they can have with them. For example, upper castes will not accept food from those of a lower caste, while lower castes will accept food from those above them. Caste status is also ascribed at birth and has nothing to do with an individual’s achievements. A Brahmin peasant remains a Brahmin while an “untouchable” engineer is still an “untouchable”. This system persists in India today, though the government does provide affirmative action in order to uplift members of “backward” castes.

Coming from a Pakistani background, I was not familiar with the operation of the caste system in daily life. Though Pakistan is a highly socially stratified society, this system has no religious sanction. In Islam, all believers are considered equal in the eyes of Allah. Unlike in India, where until recently, “untouchables” could not go into several temples, all social classes pray together in the same mosques. This fact is highlighted in one of the famous couplets from Allama Iqbal’s poem “Shikwa” (the complaint) which states: “Ek hi saf mein khare ho gaye Mahmood-o-Ayaz/ Na koi banda raha aur na koi banda nawaz” (Mahmood the king and slave Ayaz, in line as equals stood arrayed/ The lord was no more lord to slave: while both to the One Master prayed). At least in religious terms, one Muslim is not better than any other, no matter what his social status. Of course, this does not mean that social stratification ceases to exist. To this day, rich Pakistani families have separate utensils in their homes which are to be used by the servants. Punjabi Christians who engage in janitorial work are still known as “chuhras”, a derogatory reference to their pre-conversion caste status as “untouchables”. However, unlike the Hindu caste system, social class in Pakistan is not based on ascribed status. If someone from a low socio-economic background attains an education and a well-paying job, he or she will no longer be treated as belonging to their previous socioeconomic group. This is a major difference from India, where one’s caste remains salient, no matter one’s economic status.

A first hand account of caste in India is given in Sujatha Gidla’s recent book “Ants Among Elephants: An Untouchable Family and the Making of Modern India”. Gidla was born into an “untouchable” family in the southern Indian state of Andra Pradesh. Through the story of her ancestors, she presents a portrait of India from the end of British rule to the 1990s. It is particularly interesting to note that while her family is Christian (a religion in which there is technically no caste), they are still considered “untouchable” in Hindu society. Gidla writes: “Christians, untouchables—it came to the same thing. All Christians in India were untouchables, as far as I knew (though only a small minority of all untouchables are Christian.) I knew no Christian who did not turn servile in the presence of a Hindu. I knew no Hindu who did not look right through a Christian man standing in front of him as if he did not exist. I accepted this. No questions asked” (Gidla 5). Caste is so pervasive in India that it applies even to those groups whose religions formally believe in equality. Continue reading Ants Among Elephants: A Portrait of Untouchability in India

BP may have just jumped the shark

In the never-ending saga of BP, we may have just hit one of the more outlandish claims:

“Like I said, I’m not defending his comments. I wouldn’t have made them.

Regardless of any provocation, calling someone ‘subhuman’ and ‘neanderthal’ is not on—especially when those words are used by a Brahmin. It’s casteist.”

I’m fully in favour of interrogating caste. But the idea that the twice-born must exercise an extra layer of self-censorship before using a generic insult is excessive. An insult is an insult; attaching caste-specific moral disclaimers to ordinary online behaviour doesn’t clarify anything. It just adds ritual guilt where none is needed.

I support the critique of caste bias, but my fundamental sympathies are with Dharmic civilisation; precisely because Dharma is pluralistic enough to allow a hundred flowers to bloom. That pluralism should extend to how we discuss caste, not collapse into moral policing tied to someone’s birth category.

Mid-Nov Circular

Dear all,

With everything going on in the last 48 hours, we wanted to send a short note to everyone directly. BP has sputtered back to life in the past year, and with that revival comes all the familiar subcontinental pathologies: everyone believes they’re right, everyone believes moderation is biased, and everyone believes someone else is being unfair. In that sense, BP is working exactly as it always has.

We want to restate something very clearly: we’re not going to run a hyper-moderated blog. It takes too much time, too much energy, and, crucially, it’s an unfunded mandate. Nothing is more dispiriting than a dead space. Our approach has been simple and consistent:

1. Authors control their own threads.

If things escalate on your post, you shut it down when and where you see fit. That’s the cleanest system and the only one we can realistically sustain.

2. No bans, shadow bans, or entrapment games.

Once we go down the path of micro-policing, BP loses its character. That’s not the direction we want to take.

3. We do not manufacture controversy.

If anything, the only thing we are biased toward is what the audience reads and engages with. That’s it. Everything else is noise.

Reflections:

Some of you will have seen the recent exchanges where accusations were thrown in both directions, and where intentions were questioned. Without going into details: this is exactly how online political communities melt down; by assuming the worst in each other and by escalating minor provocations into existential battles. It’s the same pattern we saw a couple of years ago at a public talk by Rahul Gandhi in Cambridge: someone asked a loaded, “gotcha” question, the out of context reply went viral, people got outraged, and the whole thing became a cycle of reaction and overreaction. We’re drifting into the same dynamic.

Let’s not.

BP works only when people post, comment, disagree, and move on. If that stops, the blog dies. And as Omar’s recent post highlighted, we want authors to write more, not less.

So our simple request is this: Calm down, carry on, manage your own threads, and do not fall prey to the outrage factory.

If you feel strongly about a situation, reach out; if you want more balance, we’re happy to add an additional admin to offset the load (BP’s editorial board already functions with more factions than the Lebanese Parliament); if something crosses a line, handle it on your post. But let’s not turn BP into a miniature Whitehall where everything becomes bureaucratised. We’ve done extremely well this past year. Let’s keep the energy without burning down the house.

Warmly.

Calm Down and Carry on.

Dear all,

I have not been busy elsewhere and dont get to pay much attention to the blog and unfortunately, we seem to be seeing a lot of harsh comments and blog posts and general unhappiness. I am not promising miracles (I think the comment section will remain something of a mess, but we will try to clean up even there) but I hope we can get on even keel soon. Please do stick around, we will try to make some improvements and if you are an author who has not written for a long time, please do write more so that the quality of the posts can go up..

Omar

Bangladesh’s ousted PM Hasina sentenced to death for students crackdown

Note: BP really needs a Bangladeshi contributor so we can get some analysis of other South Asian countries rather than interminable back and forth about India and Pakistan

From DAWN:

A Bangladesh court sentenced ousted Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina to death on Monday, concluding a months-long trial that found her guilty of ordering a deadly crackdown on a student-led uprising last year.

The ruling comes months ahead of parliamentary elections expected to be held in early February.

Hasina’s Awami League party has been barred from contesting and it is feared that Monday’s verdict could stoke fresh unrest ahead of the vote.

The International Crimes Tribunal, Bangladesh’s domestic war crimes court located in the capital Dhaka, delivered the guilty verdict amid tight security and in Hasina’s absence after she fled to India in August 2024.

Personally, I have mixed feelings about this. Sheikh Hasina was a dictator (and arguably an Indian puppet) so I’m not particularly fond of her. She does need to pay for her crimes. However, I don’t believe in the death penalty. This step seems to be an extremely problematic one for Bangladesh.

Criminal castes, religious conversion, and the idea of India ft. Nusrat F. Jafri

A clear look at how the criminal caste label continues to shape social life, how conversion becomes a route to dignity, and how these shifts speak to the larger idea of India. Nusrat F Jafri, author of In This Land We Call Home, joins to discuss the history, identity, and ground realities that still define the present.

What Is Not India Is Pakistan

As Dave mentioned, there is a lively WhatsApp group of BP authors and editors, and it inevitably shapes the comment ecosystem. But one comment on the blog stood out:

“The very foundation of Pakistan is an anti-position. What is not India is Pakistan. So isn’t it obvious?”

It’s an extraordinarily crisp description of Pakistani identity-building. What is not India is Pakistan. That is not a slur; it is, in many ways, a psychologically accurate frame for how the state narrates itself.

What I increasingly find misplaced on this blog is the recurring assumption that Pakistanis are somehow “Indians-in-waiting,” or that Punjab is “West Punjab,” Pakistan “Northwest India,” or Bangladesh “East Bengal.” These are irredentist projections that simply do not match lived identities. This is not “North Korea” or “East Germany,” where both sides continue to imagine themselves as fragments of one common nation.

Yes, Pakistan consumes Bollywood and Hindi music, which themselves derive from Mughal and Indo-Persian syncretic traditions. Yes, Pakistan is culturally embedded in the greater Indo-Islamic civilizational sphere. But emotionally, Pakistan has severed itself from the Indian Subcontinent as a cohesive landscape. It has constructed a hybrid identity; part Turko-Persian, part Islamic internationalist, part anti-India.

I don’t personally agree with this move, and my own trajectory has been toward a strong Hinducised, Dharmic identification. But my view is irrelevant here. What matters is that Pakistani identity is defined negatively; as the commentator put it, “What is not India is Pakistan.”

Whether that is healthy or sustainable is another matter. But identities can persist in unhealthy configurations for a very long time; the stock market can be irrational longer than your liquidity can survive.

Open Thread – PakMil manipulates the ‘constitution’ yet again.

plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose