From my SubStack:

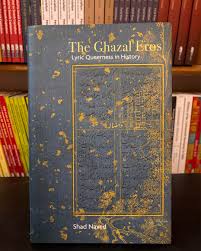

The Ghazal–a love lyric in Arabic, Persian, Ottoman Turkish and Urdu– has historically been defined as “talking with or about women”. For example, in his Persian dictionary compiled in eighteenth century Hindustan, Tek Chand Bahar defines the genre as follows: “Talk about women, or talking about making love with them or a poem that is said in praise of women”. However, as Shad Naved– a professor of literature and translation at Dr. B.R. Ambedkar University, Delhi– argues in his book The Ghazal Eros: Lyric Queerness in History (Tulika Books 2025), “the central role the ghazal played in the development of literature in Persian and Urdu during these six centuries is as a love lyric, in which men speak almost never about women but about other men and youthful boys–with the exception of Arabic, in which a strong current of love poetry about women written by male poets played an important role in the development of the ghazal” (Naved 9). Naved goes on to ask the crucial question: Why do the dictionaries lie?

For the purposes of this review, I will restrict my discussion to chapter one of Naved’s book–entitled “Sexual Orientation as Style”. It is this chapter which lays out the basis of Naved’s argument. Part Two of the book consists of three chapters that provide specific examples of lyric queerness in the Urdu ghazal. For example, chapter 2 focuses on the poet Mir Taqi Mir (1723-1810)–specifically on his poems dealing with “boy-love”. These detailed examples are outside the scope of my review. Continue reading Review: The Ghazal Eros: Lyric Queerness in History by Shad Naved